Understanding Section 301 IPC and Transferred Malice

- Rare Labs

- Dec 16, 2025

- 17 min read

Section 301 IPC is a fascinating corner of the Indian Penal Code, built on a principle you might have heard called the doctrine of transferred malice. In simple terms, it holds a person responsible for the death of an unintended victim, treating the act just as seriously as if they'd hit their original target. The law essentially ‘transfers’ the criminal intent (mens rea) from the person they meant to harm to the person who was actually killed.

Decoding the Principle of Transferred Malice

Think of it like this: an assassin aims a pistol at his target, intending to kill him. He pulls the trigger, but at that exact moment, his target ducks. The bullet misses him completely and strikes a bystander, killing them instantly. The assassin never intended to kill the bystander, but his intention to kill someone was crystal clear. This is the exact scenario Section 301 IPC was designed to address.

This legal doctrine ensures that a criminal can't just get away with a lesser charge by claiming it was an accident or that they had bad aim. If you set out to commit a deadly act, the law says you're on the hook for the fatal consequences, no matter who the victim turns out to be. The malice, or criminal intent, follows the bullet.

The Legal Framework of Transferred Malice

This isn't just a clever interpretation by judges; it's explicitly written into the law. Section 301 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) is the bedrock of this principle, a crucial part of our criminal jurisprudence since the code was first drafted back in 1860. It makes sure that an accused person is held liable for murder or culpable homicide even if the person who died wasn't the one they had in their sights.

The official text of the law puts it in more formal language:

If a person, by doing anything which he intends or knows to be likely to cause death, commits culpable homicide by causing the death of any person, whose death he neither intends nor knows himself to be likely to cause, the culpable homicide committed by the offender is of the description of which it would have been if he had caused the death of the person whose death he intended or knew himself to be likely to cause.

It's a principle that shares some DNA with other legal concepts like vicarious liability, where one person can be held responsible for the actions of another. If you're interested in that, you can dive deeper into our guide on top vicarious liability cases shaping Indian law to see how responsibility can be legally assigned.

How Legal AI Can Help Untangle These Concepts

Getting to the heart of foundational principles like transferred malice means digging through a mountain of case law and interpreting dense statutory language. This is where a specialized Legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer for legal professionals. It can scan decades of High Court and Supreme Court judgments on Section 301 in seconds, pinpointing how judges have defined "intention" and "knowledge" over the years. By pulling together the most relevant precedents almost instantly, Draft Bot Pro gives lawyers the power to build rock-solid arguments and truly understand the nuances of a case in a fraction of the time.

To make things even clearer, here's a quick summary of the core components of this section.

Section 301 IPC at a Glance

This table breaks down the essential elements of Section 301 IPC into a simple, easy-to-understand format.

Component | Explanation |

|---|---|

Doctrine | Transferred Malice (also known as Transmigration of Motive). |

Core Idea | The mens rea (criminal intent) you had for your intended victim gets transferred to the actual victim. |

Requirement | You must have had the intention or knowledge that your act could cause the death of the original target. |

Outcome | You're held liable for the same offence (e.g., murder) as if you had successfully killed the person you intended to. |

In short, the table shows that your original criminal intent is what ultimately defines the crime, regardless of who ends up being the final victim.

The Essential Ingredients and Role of Mens Rea

To really get to grips with Section 301 IPC, you have to break it down into its core parts. Think of it like a recipe: for the prosecution to secure a conviction, they need to prove every single ingredient beyond a reasonable doubt. If even one is missing, the whole case can fall apart.

These ingredients work together to create what we call a 'legal fiction'. Essentially, the law builds a bridge, transferring the criminal intent from the person you meant to harm to the person who was actually harmed. This ensures that the accused is still held responsible for the deadly result of their actions.

The Three Pillars of a Section 301 Case

Every case that leans on Section 301 of the IPC is built on three crucial pillars. All three must be firmly in place and proven for the doctrine of transferred malice to kick in.

Existence of Mens Rea: This is the mental part—the "guilty mind." First and foremost, the prosecution has to show that the accused had the initial intention or knowledge that their act was likely to kill a specific person (the intended victim). This is the absolute cornerstone.

Commission of Actus Reus: This is the physical part—the "guilty act." The accused must have actually done something, like firing a gun, using poison, or landing a blow, to follow through on that deadly intent.

Death of an Unintended Person: Finally, there's the tragic result. The act must lead to the death of someone other than the person the accused meant to kill or knew they were likely to kill.

When these three elements line up, Section 301 IPC comes into play, making sure the offender is judged on their original lethal intent, not on the accidental identity of their victim.

The Central Role of Mens Rea

At the heart of any Section 301 IPC case is the concept of mens rea, or criminal intent. The law is crystal clear on this: the intent that counts is the one aimed at the original target.

The court doesn't ask, "Did the accused mean to kill Person B (the actual victim)?" Instead, the question is, "Did the accused mean to kill Person A (the intended victim)?"

If the answer is yes, that intent is legally carried over to Person B. It's a powerful tool that stops an offender from dodging a murder charge by simply saying, "Oops, wrong person." The law's stance is that if you intended a fatal outcome, you own the full responsibility for whichever death occurs.

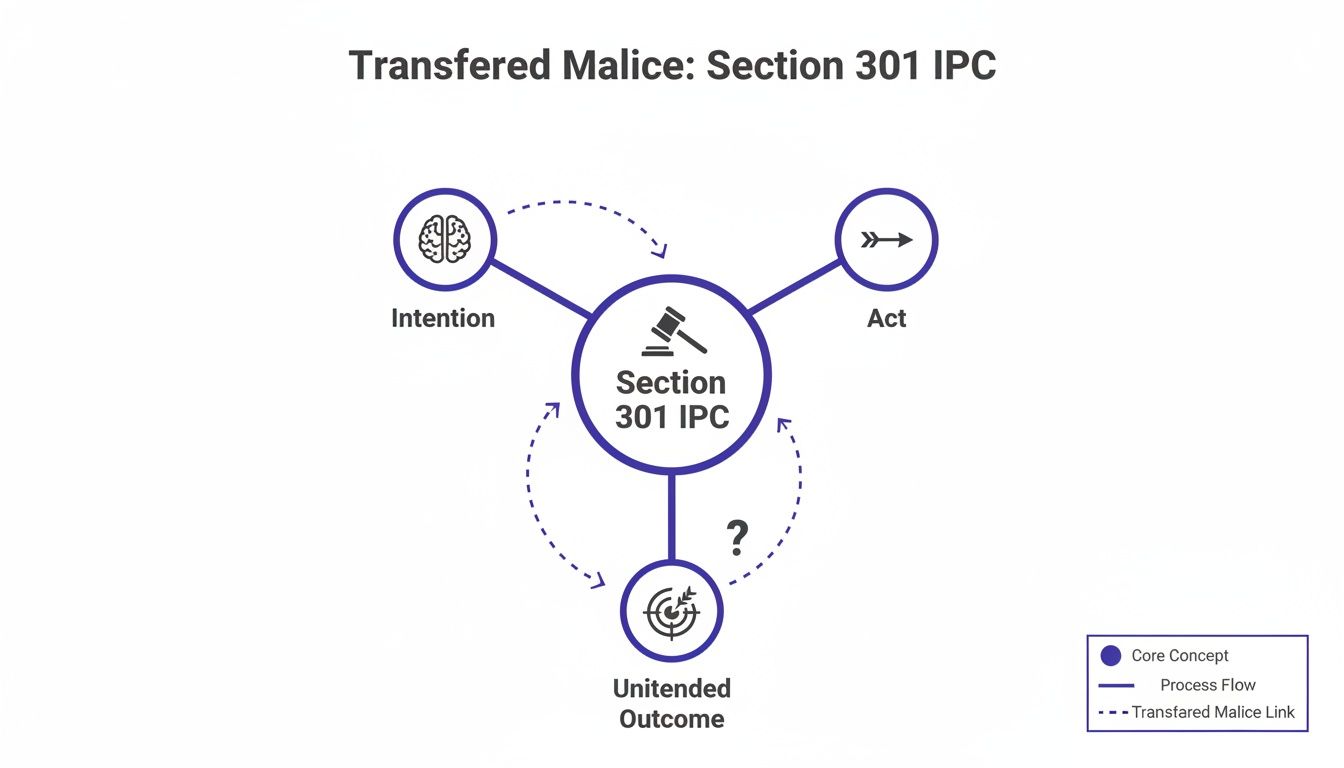

This diagram helps visualise how the pieces of transferred malice fit together under Section 301 IPC.

As you can see, the initial intention is the engine that, when combined with a physical act, drives the criminal liability for the unintended consequence.

A Quick Note: The difference between 'intention' and 'knowledge' is a fine but important one. Intention is about wanting a specific result to happen. Knowledge, on the other hand, means the accused was fully aware their act was so dangerous that it would almost certainly cause death, even if they didn't actively want that person to die.

Proving Intent in Complex Cases

Proving what was going on inside someone's head—their mens rea—is often the toughest part for any prosecutor. This is where sharp legal work and a deep dive into case law become absolutely vital.

For instance, if the original plan was only to cause serious injury (grievous hurt) and not death, Section 301 wouldn't apply. You'd be looking at different charges, like those covered in our explainer on Section 325 IPC punishment.

This is also where a Legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can give a legal team a serious edge. Lawyers can use it to instantly sift through a massive library of judgments on mens rea in culpable homicide cases. The AI can pinpoint key precedents and similar situations where intent was either successfully proven or debunked, helping to build a much stronger, evidence-backed argument for the courtroom.

Landmark Cases That Shaped Section 301 IPC

Legal principles aren't just abstract ideas; they're forged and refined in the crucible of the courtroom. The doctrine of transferred malice, enshrined in Section 301 IPC, has been moulded over the years by a series of landmark judicial decisions. These cases tell the real-world story of how the law stops offenders from escaping justice simply because of a tragic miscalculation or a poorly aimed attack.

When you dig into these judgments, a clear and unwavering stance from the judiciary emerges: a lethal intention, once formed, remains lethal in the eyes of the law, no matter who becomes the final victim.

The Foundational Rajalakshmi Poisoning Case

One of the earliest and most influential cases that truly cemented how Section 301 IPC is applied was the P.S. Rajalakshmi case. In this tragic incident, the accused meant to poison one person, but through a cruel twist of fate, someone else consumed the poison and died. The defence tried to argue that since there was no direct intent to kill the actual victim, the charge should be less severe.

The Supreme Court disagreed, and did so emphatically. It applied the doctrine of transferred malice directly, holding that the original intent to cause death was all that mattered. The judgment set a powerful precedent: the crime is defined by the initial mens rea, not by the identity of the person who ultimately dies. The court ruled that the culpable homicide committed was of the same nature as if the intended person had been the one to die.

Reinforcing The Doctrine In Rajbir Singh vs State of UP

Decades later, the Supreme Court had to hammer this principle home again in the notable case of Rajbir Singh vs. State of UP (2006). Here, the accused fired a gun intending to kill one person, but the bullet missed and fatally struck an innocent bystander. In a surprising move, the Allahabad High Court had acquitted the accused of murder, failing to correctly apply Section 301.

The Supreme Court sharply criticised this oversight. It overturned the acquittal and convicted the accused under Section 302 (Murder) read with Section 301 IPC. The court's logic was crystal clear: the act was done with the intention of causing death, and the fact that an unintended person died was irrelevant to the nature of the offence. The malice was simply transferred from the intended target to the actual one. This judgment served as a stern reminder to lower courts about the mandatory application of Section 301 IPC in these situations.

A Modern Example: The Md Subham Case

The principles upheld in these older cases are still very much alive and kicking in modern courtrooms. A practical example is the Md Subham case from Kolkata (2013). During a chase, a bullet intended for one individual struck and killed a police officer. Once again, the defence argued there was no specific intent to kill the officer.

Unsurprisingly, the court, relying on the solid foundation of transferred malice, found the accused guilty of murder. This case shows just how robust the principle is, applying across all sorts of scenarios, from poisoning to shootings. It reinforces the core idea that the law follows the criminal intent, not the unlucky victim. This consistent interpretation across many of the top landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India shows how foundational legal principles are upheld through generations.

Insight: The judiciary's consistent application of Section 301 IPC reveals a core legal philosophy: a person cannot benefit from their own criminal ineptitude. The law is designed to prevent an offender from claiming a lesser punishment just because their aim was poor or their plan went awry. The focus stays squarely on the original deadly intent.

Comparison of Key Judgments on Section 301 IPC

To give you a clear snapshot, the table below compares the pivotal cases that have defined how transferred malice is applied in India. These judgments have been crucial in interpreting and cementing the doctrine's place in our criminal law.

Case Name | Year | Key Legal Principle Upheld |

|---|---|---|

P.S. Rajalakshmi Case | Mid-20th Century | Established that the original intent to kill is transferred to the unintended victim, defining the crime's nature. |

Rajbir Singh vs. State of UP | 2006 | Reinforced that applying Section 301 is mandatory; failing to do so is a judicial error. The charge is murder if the original intent was murderous. |

Md Subham Case (Kolkata) | 2013 | Confirmed the doctrine's application in modern, fast-moving criminal scenarios like a shooting during a chase. |

Looking at these cases side-by-side, you can see a direct line of consistent legal reasoning. The courts have left no room for ambiguity when it comes to an act that begins with a murderous intent.

How Legal AI Simplifies Case Law Analysis

For any legal professional, tracing the evolution of a legal doctrine through decades of case law is a mammoth task. This is exactly where a Legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro becomes a game-changer. It can instantly scan and analyse thousands of judgments related to Section 301 IPC, identifying patterns in how courts have interpreted mens rea and applied the doctrine over time.

Instead of spending days buried in a law library, a lawyer can use Draft Bot Pro to:

Trace Precedents: Quickly find and summarise the chain of cases from Rajalakshmi to modern rulings.

Identify Key Arguments: Pinpoint the exact legal reasoning used by judges in similar factual scenarios.

Strengthen Submissions: Build powerful arguments by citing the most relevant and authoritative judgments.

This frees up legal teams to focus on building a winning strategy, armed with a comprehensive understanding of how Section 301 has been shaped by the courts.

Punishment and Distinctions from Other Offences

So, what happens when a court actually applies Section 301 IPC? It’s a common mistake to think this section has its own punishment. It doesn’t. Think of it more like a legal signpost, pointing the court to the right penal section based on what the offender originally set out to do.

The doctrine of transferred malice isn't about creating a new offence. It's a clarifying rule. It makes sure that the death of the person you didn't mean to kill is treated with the same gravity as if you'd hit your original target.

Because of this, the punishment isn’t found in Section 301 at all. It's dictated by the kind of culpable homicide the person intended to commit in the first place. This is a crucial link, connecting the act to one of two major punishments in the IPC.

Linking Intent to Punishment

The court's first job is to figure out the mens rea (the criminal intent) the accused had towards their intended victim. That initial state of mind is what decides the final sentence.

If the intent was murder: If the accused's actions were so dangerous and pre-planned that they count as murder under Section 300, the punishment will be handed down under Section 302 (Punishment for Murder). This is the big one, leading to life imprisonment or, in the "rarest of rare" cases, the death penalty, along with a fine.

If the intent was culpable homicide: If the act was less severe, amounting to culpable homicide not amounting to murder (as defined in Section 299), then the punishment comes under Section 304 (Punishment for Culpable Homicide Not Amounting to Murder). This usually means imprisonment for life or up to ten years, plus a fine.

Put simply, the severity of the original intent is mirrored directly in the final sentence.

Differentiating Section 301 from Related Offences

To really get a grip on what Section 301 is, you also need to understand what it isn't. The dividing line, every single time, is the initial mens rea. Let's see how it stacks up against an offence it's often confused with.

The most important distinction is with Section 304A, which covers causing death by a negligent act.

Insight: For a prosecutor, this is where strategy becomes everything. You have to build a rock-solid case proving that the accused first intended to cause death. If you can't establish that specific mens rea, a Section 301 charge will crumble, and the case could be downgraded to a lesser offence like causing death by negligence—which carries a much lighter sentence of up to two years.

Picture this: A driver is speeding recklessly down a busy street and hits a pedestrian, killing them. While tragic, the driver didn't intend to kill anyone. This is a textbook case for Section 304A (Causing Death by Negligence). Now, contrast that with someone who shoots at an enemy, misses, and kills a bystander. The initial intent to kill is what brings the case squarely under Section 301 IPC.

While the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) doesn't provide specific data for Section 301 cases, it's clear they are a factor in the wider statistics on violent crime. For example, murder cases—which can often be the end result of a Section 301 application—jumped by 10.2% from 25,968 in 2021 to 28,522 in 2022. The stakes are incredibly high. Judicial data shows that convictions in such cases can lead to the death penalty in 1.2% of instances and life imprisonment in a staggering 92%, showing just how seriously our courts treat these crimes. You can dive deeper into these judicial statistics on criminal law for a fuller picture.

How Draft Bot Pro Prevents Critical Errors

Framing charges is one of the most high-stakes steps in any criminal case. One small mistake here can derail the entire prosecution. This is precisely where a Legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro proves its worth.

For prosecutors, Draft Bot Pro can generate charge sheets that are both precise and legally airtight. By analysing the case facts, it can correctly flag the applicability of Section 301 and link it to the right penal section, like Section 302. This ensures the charges perfectly mirror the alleged crime and intent, shutting down technical loopholes a defence lawyer might try to exploit later. It helps build a strong foundation for the prosecution's case right from the start.

Navigating the Courtroom: Procedure and Defence

Knowing the theory of Section 301 IPC is one thing, but seeing it play out in a real case is something else entirely. Once a charge sheet lands, the procedural wheels start turning, all governed by the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). This isn't a flexible process; it's a defined path from accusation to trial, and understanding each step is vital for both sides.

When Section 301 is brought into the picture, it's almost always attached to a very serious offence, like murder under Section 302 or culpable homicide under Section 304. This isn't taken lightly, and the procedural classification reflects that gravity.

Cognizable Offence: The police don't need to wait for a warrant. They can make an arrest on the spot.

Non-Bailable Offence: Getting bail isn't a right; it's a long shot. The court has full discretion, and it's often denied in such serious cases.

Triable by Court of Session: This isn't a matter for a Magistrate. The case goes straight to a higher court, the Court of Session, which handles the most severe criminal trials.

This framework immediately signals how serious the situation is, setting the stage for a tough legal fight.

How to Build a Strong Defence

The doctrine of transferred malice is a powerful weapon for the prosecution, but it's not foolproof. A solid defence strategy is all about picking apart the prosecution's case, zeroing in on the essential ingredients—especially the crucial element of mens rea, or criminal intent. Your job is to inject reasonable doubt.

Here are a few angles that a sharp defence lawyer will explore:

Attack the Original Intent: The entire case hinges on the accused's original intention to kill. The defence can hammer away at this point, arguing that the intent was never there to begin with. Maybe the plan was just to cause a simple injury or even grievous hurt, but not death. If you can prove that, the foundation of the Section 301 charge crumbles.

Dispute the 'Knowledge' Requirement: The prosecution needs to show the accused knew their act was so dangerous it would almost certainly cause death. A defence can argue this 'knowledge' was absent. This is a strategic move to reframe the incident, potentially downgrading the charge from murder to a lesser form of culpable homicide.

Challenge the Act Itself (Actus Reus): Sometimes, the best defence is to question the chain of events. Was the accused's action really the direct cause of death? Or did something else—an intervening event—break that chain? You could argue that the death of the unintended victim was a tragic coincidence, not a direct consequence of the act.

Insights: Remember, in a criminal trial, the onus is entirely on the prosecution. They have to prove every single element of their story beyond a reasonable doubt. A skilled defence lawyer doesn't necessarily need to prove innocence; they just need to find the cracks in the prosecution's case and create enough doubt for an acquittal.

Using Legal AI to Your Advantage

In the high-stakes world of a Section 301 IPC trial, modern tools can make a world of difference. A legal AI platform like Draft Bot Pro is no longer just a fancy research tool; it's a strategic partner for the defence team.

Think of it this way: Draft Bot Pro can comb through every piece of the prosecution's evidence—the FIR, witness statements, forensic reports—and flag inconsistencies a human might miss. But its real power lies in its ability to scan a massive database of past cases, finding acquittal judgments where similar arguments succeeded. This gives defence lawyers a treasure trove of precedent and proven strategies, allowing them to build a much more powerful, evidence-backed case in court.

Frequently Asked Questions About Section 301 IPC

Even with a clear explanation, the real-world application of legal principles can throw up some tricky questions. Section 301 IPC is no different. Let's tackle some of the most common practical queries about the doctrine of transferred malice to help you see how it plays out in real legal scenarios.

These are the kind of "what if" situations that often come up, and understanding them is key to truly grasping the core concepts.

What Happens If the Intended Victim Also Dies?

This is where a tragic situation gets even more complex from a legal standpoint. If an attacker's actions kill both the person they meant to kill and an innocent bystander, the principle of transferred malice doesn't just apply—it doubles down.

The accused will face a straightforward charge for the death of the intended victim, be it for murder or culpable homicide. But it doesn't stop there. Section 301 IPC kicks in for the unintended victim, effectively copying the original criminal intent over to that second act.

This means the accused can be tried for two separate offences, one for each life lost. The court will see them as distinct crimes, and the sentences could even be set to run one after the other.

Does Section 301 Apply If the Intent Was Only Grievous Hurt?

No, and this is a critical distinction to make. The wording of Section 301 is very precise: it only triggers when an act is done with the "intention or knowledge to cause death." If the original plan was just to cause serious harm (grievous hurt) and that act accidentally kills someone else, you can't use Section 301.

In that scenario, the case would be handled under different parts of the IPC. It would most likely fall under Section 304 (culpable homicide not amounting to murder), or perhaps another provision depending on the specifics. The key ingredient for Section 301 IPC—the initial mens rea to cause death—is missing, so the doctrine of transferred malice simply doesn't fit.

Insights: The law's sharp focus on the initial intent to cause death is what gives Section 301 its power. It carves out a very specific kind of criminal liability, making sure the gravest consequences are reserved for acts that started with a lethal state of mind.

How Does a Legal AI Like Draft Bot Pro Help in a Section 301 Case?

A specialised legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer for lawyers on either side of a Section 301 IPC case. Think of it as a super-efficient research assistant that gives you a strategic edge by sifting through massive amounts of legal data in seconds.

For the prosecution:

Strengthen Arguments: It can instantly pull up judgments where transferred malice was successfully applied in similar situations, giving you solid precedents to build your case on.

Draft Precise Charges: The AI helps frame legally sound charge sheets, ensuring Section 301 is correctly linked with other penal sections like 302 or 304, which helps avoid procedural slip-ups.

For the defence:

Identify Weaknesses: It can scan the prosecution's documents for any holes or inconsistencies in their argument about the accused's intent.

Formulate Strategy: By finding past acquittal judgments in comparable cases, it helps lawyers build a defence strategy based on arguments that have already worked in court.

In short, it acts as a hyper-focused legal researcher, digging up the most relevant information you need to either prove or challenge that crucial element of criminal intent.

Is Section 301 IPC Identical to English Common Law?

While Section 301 IPC definitely has its roots in the English common law idea of 'transferred malice', they aren't exactly the same. The biggest difference is in how they are structured.

In India, the principle is codified—it's written down as a specific statute. This means Indian courts have to apply it strictly based on the text of Section 301. On the other hand, the English common law doctrine is more of a judicial principle that has evolved over centuries through court decisions, giving it a bit more flexibility. This codification makes the application of transferred malice in India much more precise and bound by the letter of the law.

Ready to elevate your legal practice? Draft Bot Pro is the most verifiable and affordable Legal AI built by Indian lawyers, for Indian lawyers. Trusted by over 46,379 legal professionals, it helps you draft flawless documents and conduct pinpoint-accurate legal research backed by real case law. Start working smarter, not harder, by visiting https://www.draftbotpro.com today.