A Litigator's Guide to Order 7 Rule 14 of the CPC

- Rare Labs

- Jan 26

- 17 min read

Order 7 Rule 14 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), 1908, is one of those foundational rules every litigator needs to have etched in their mind. It essentially says that when you file a plaint, you must simultaneously produce every single document in your possession that your claim relies upon. This isn't just a suggestion; it's a critical procedural step that sets the stage for the entire lawsuit, ensuring transparency right from the get-go and preventing nasty surprises down the line.

The Core Mandate of Order 7 Rule 14

Think of filing a plaint like building a house. Order 7 Rule 14 is the rule that demands you lay down a solid, complete foundation before you even think about putting up the walls. If your lawsuit is built on certain documents—a contract, a promissory note, a series of emails—this rule mandates that you must physically produce and file them along with your plaint.

Skip this step, and your entire legal structure is at risk of crumbling. The whole point is to create a level playing field. The defendant gets a clear, immediate picture of the evidence they need to respond to. This simple act of upfront disclosure helps streamline the entire judicial process, allowing for issues to be framed quickly and killing the tactic of "trial by ambush," where one party springs unexpected evidence on the other mid-proceedings.

Why Early Production Matters

The logic behind this rule is simple but incredibly powerful. By forcing the plaintiff to lay their cards on the table from day one, the court ensures the litigation proceeds fairly. This early disclosure is a game-changer for several reasons:

It kills delays. No more last-minute document submissions that grind the proceedings to a halt and lead to endless adjournments.

It creates clarity. The defendant knows exactly what they're up against and can prepare a defence that is specific and effective, rather than just a blanket denial.

It encourages settlement. When both sides can see the strength of the evidence (or lack thereof) early on, it often pushes them towards a more realistic assessment of their case and opens the door for meaningful settlement talks.

Below is a quick reference table that breaks down the essentials of this rule.

Order 7 Rule 14 at a Glance

This table summarises the core requirements, exceptions, and consequences of non-compliance with Order 7 Rule 14 of the CPC.

Provision | Plaintiff's Core Duty | Result of Non-Compliance |

|---|---|---|

Order 7 Rule 14(1) | File all documents in your possession or power that the suit is based on. | You cannot use these documents as evidence later without the court's permission. |

Order 7 Rule 14(2) | List all other documents you rely on but are not in your possession. | If the documents are not listed, they may not be admissible later. |

Order 7 Rule 14(3) | This rule does not apply to documents produced for cross-examination or to refresh a witness's memory. | These specific-use documents are an exception and can be produced later. |

Understanding these distinctions is key to ensuring your evidence is admissible when it counts.

Insights: The Role of Legal AI in Compliance

Getting Order 7 Rule 14 right on the first attempt is non-negotiable. A simple oversight, like forgetting to file a crucial email, can mean that the evidence is barred later, potentially sinking your entire case. This is where modern legal tech can be a lifesaver.

An AI-powered legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro acts as your procedural safety net. It can analyse the facts and arguments in your draft plaint and automatically generate a checklist of necessary documents. This ensures that every piece of evidence you're relying on is identified and accounted for before you file. It's a simple way to prevent a procedural misstep that could prove fatal to your case. You can learn more in our detailed litigator's guide to production of documents under CPC.

The Strategic Importance of Early Document Production

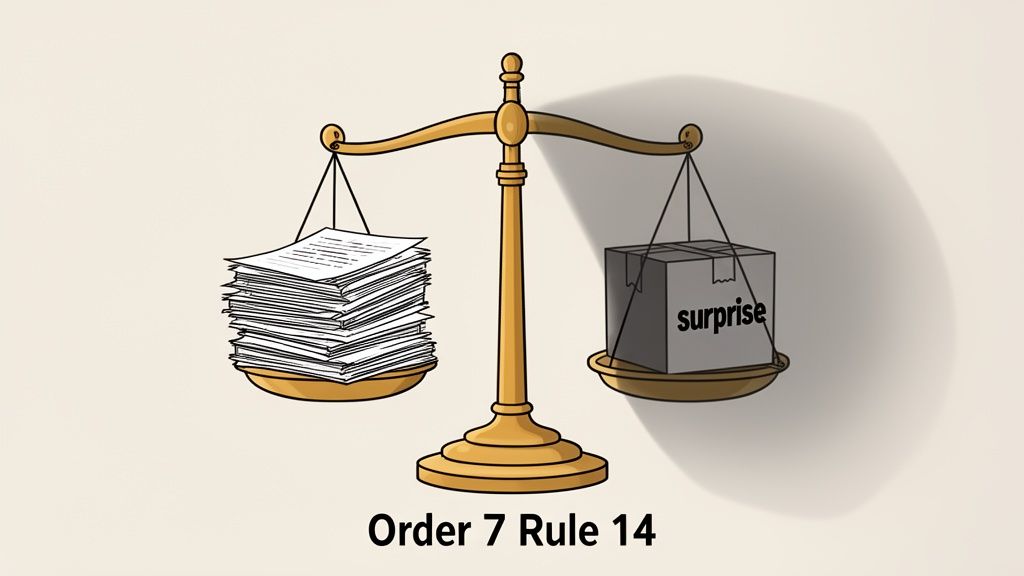

Understanding the letter of the law is one thing; getting a feel for its strategic soul is something else entirely. Order 7 Rule 14 of the CPC isn't just a procedural hoop to jump through. It exists for a profound and practical reason that gets to the very heart of what makes litigation fair.

Its main job is to kill the tactic of "trial by ambush." Just imagine you're in the middle of a trial, and the other side suddenly whips out a surprise document. You'd be caught completely flat-footed, with no time to challenge it, verify it, or prepare a proper response. It would throw the entire case into chaos and completely undermine the fairness of the whole process.

This rule essentially forces the plaintiff to put all their cards on the table from day one. By laying out the foundational documents with the plaint, they give the defendant a clear and honest picture of the case they have to answer. This allows the defence to be meaningful and targeted, not just a shot in the dark.

Streamlining the Entire Judicial Process

Following Order 7 Rule 14 diligently isn't just about avoiding trouble; it's smart, efficient lawyering. When all the key documents are on the record from the start, the whole judicial machine runs faster. In a system like India's, where delays can be crippling, this is a massive advantage.

This initial disclosure helps the court frame the issues in dispute much more quickly and accurately. With a clear view of the evidence, both sides can cut to the chase and focus their arguments on the real points of contention. The result? A more streamlined and faster resolution.

The consequences of getting this wrong are very real. A recent Bar Council of India report highlighted that a staggering 18% of civil suit dismissals under Order 7 Rule 11 (rejection of plaint) are directly tied to failures in document production under Rule 14. You can discover more insights on how technology addresses these procedural challenges in Indian legal tech.

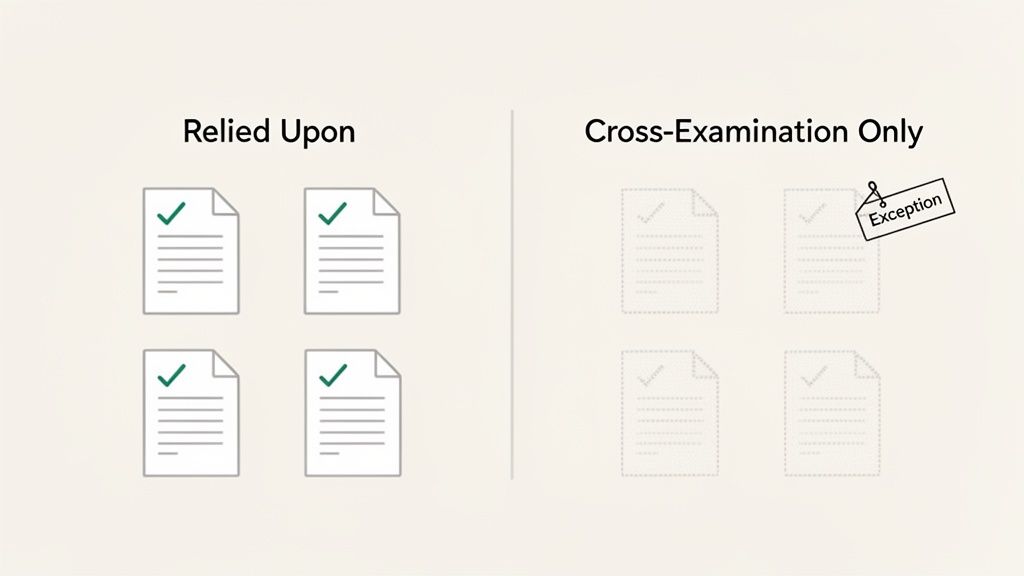

Documents Relied Upon vs. Documents for Cross-Examination

Here’s where a lot of people get tripped up. The rule makes a critical distinction between two types of documents, and confusing them can lead to serious mistakes.

Documents Relied Upon: Think of these as the pillars of your case. They are the documents you will actively use to prove your claim. Filing these with the plaint is mandatory.

Documents for Cross-Examination: This is your secret weapon. These documents aren't part of your primary evidence but are kept in reserve to challenge the credibility of the defendant's witnesses during cross-examination. These are the key exception and you don't have to file them upfront.

Failing to grasp this difference can mean you either show your hand too early, revealing your cross-examination strategy, or worse, you fail to produce mandatory evidence, which the court can then prevent you from using later.

Insights: Compliance as a Risk Management StrategyViewing Order 7 Rule 14 as just another box to tick is a rookie mistake. It’s a foundational risk management strategy. A failure here creates an immediate vulnerability in your case that a sharp opponent will pounce on. This is where a strategic legal AI can be an invaluable partner. For instance, Draft Bot Pro can analyse your draft plaint and case notes, helping you distinguish between documents you rely on and those best kept for cross-examination. It helps meticulously organise and list every necessary attachment, ensuring your case is built on a rock-solid, compliant foundation right from the first filing.

Navigating the Scope and Key Exceptions

To really get to grips with Order 7 Rule 14, you need to understand not just what it covers, but more importantly, what it leaves out. The rule draws a very clear line in the sand. On one side, there's a mandatory duty you simply can't ignore. On the other, there's a powerful exception that's pure trial strategy. Getting this distinction right from the very beginning is fundamental to building a solid, procedurally sound case.

The core mandate is simple and direct: if you sue someone, you must produce every single document in your possession or power that you rely on to prove your claim. We're not talking about every piece of paper remotely related to the case. This is about the documents that form the very bedrock of your lawsuit—the evidence you'd point to first and say, "This is why I'm entitled to win."

This obligation is deliberately broad. The phrase "possession or power" is key here. It doesn't just mean what's physically sitting in your office file cabinet. It also covers documents you have a legal right to get your hands on, even if someone else—like your agent or a bank—is currently holding them.

The Major Exception: Documents for Cross-Examination

While the rule for your foundational documents is strict, Order 7 Rule 14 gives you a crucial strategic out. This is the exception for documents you plan to use only for the cross-examination of the defendant's witnesses.

Think of these as your trump cards. They aren't part of the main story you're telling to prove your own case. Instead, you keep them up your sleeve to challenge the credibility of the other side's witnesses or to poke holes in their testimony when they're on the stand.

Here’s how it plays out in the real world:

You're suing to recover a loan. With the plaint, you file the loan agreement and your bank statements showing the money went out but never came back. These are documents you rely on.

But you also have an email where the defendant casually admitted to a friend that they had no intention of ever repaying you. You might decide to hold this email back.

Then, during the trial, if the defendant gets on the stand and swears they always intended to pay, you can pull out that email during cross-examination. It completely demolishes their testimony.

This exception is brilliant because it means you don't have to lay all your cards on the table from day one. It preserves the element of surprise, which is often what makes a cross-examination so effective.

Handling Documents Not in Your Possession

So what happens when a document you need to rely on isn't actually with you? This is a common situation. The original contract might be with a third party, or maybe a key record is held by a government department. Order 7 Rule 14 has a clear procedure for this.

You aren't off the hook just because the document is somewhere else. You still have a duty. Here’s what you do:

Specifically list the document in the official list of documents you file with your plaint.

State clearly in whose possession or power you believe that document currently is.

By doing this, you're putting both the court and the defendant on notice. It shows you've done your homework and are being transparent, flagging the evidence you need even if you can't physically attach it just yet.

Insights: Interpreting 'Possession or Power'Courts take the phrase 'possession or power' very seriously. The plaintiff's duty isn't just to list documents they can easily find, but to make a genuine effort to obtain those they have a right to. This is where the right tools can save a lot of procedural headaches. For instance, a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can automatically generate a compliant list of documents right from the averments in your plaint. And when you flag a document as being held by a third party, it can draft the precise language required by Order 7 Rule 14, stating who has it and why it's being relied upon—ensuring you meet your procedural obligations without any guesswork.

Landmark Judgments: Where the Rule Comes to Life

The black-and-white text of Order 7 Rule 14 gives you the skeleton, but it’s the courtroom battles and judicial wisdom that put flesh on its bones. For decades, the Supreme Court and various High Courts have wrestled with its nuances, creating a rich tapestry of case law that every litigator needs to know. These judgments aren't just academic footnotes; they are the real-world playbook for using this rule effectively.

Why does this matter so much? Because these rulings draw the crucial line between a minor slip-up you can fix and a catastrophic error that gets your evidence thrown out. Courts are constantly performing a delicate balancing act—enforcing procedural discipline on one hand while ensuring justice is served on the other. Diving into these precedents shows us exactly when and why a judge might give a plaintiff a second chance to produce a document.

What Does "Relied Upon" Actually Mean?

One of the most fought-over phrases in Order 7 Rule 14 is "relied upon." It sounds simple, but lawyers have spent countless hours arguing its scope. The courts have consistently stepped in to clarify: this isn't a free-for-all to include every piece of paper remotely connected to the case. It refers strictly to the documents that are the very foundation of your claim.

The guiding principle that has emerged is this: if you can't plead and prove your case without a particular document, it is "relied upon." It's that simple. If removing the document causes your entire argument to collapse, then it absolutely must be filed with the plaint.

Think of it like this: in a suit for specific performance of a contract, the agreement to sell isn't just helpful evidence; it is the case. Similarly, in a suit to recover money based on a promissory note, that note is the central pillar of your claim. The judicial consensus is crystal clear—these foundational documents are non-negotiable.

The Court's Discretion: A Lifeline, Not a Guarantee

While the rule sets a firm deadline, it isn't completely merciless. Sub-rule (3) hands the court a crucial power: the discretion to grant leave and allow documents to be filed later. But let's be clear, this is a lifeline, not an automatic right. To get this lifeline, you need to convince the court that you have a "sufficient cause" for not producing the document with the plaint.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly warned that this discretion must be exercised with judicial wisdom, not on a whim. So, what do judges look for? A few key things:

Is it truly relevant? The document can't be a minor detail; it must be critical to reaching a just decision.

Was it an honest mistake? The court needs to see a genuine oversight, not a calculated move to surprise the other side later.

Will it prejudice the defendant? The judge will weigh whether allowing the document now would unfairly hurt the defendant, who has already built their defence around the initial set of documents.

Insights: The Power of AI in Legal ResearchKeeping pace with the constant stream of new case law is a massive headache for any litigator. A ruling from six months ago can completely change how you argue a motion for leave today. This is where an AI legal research tool like Draft Bot Pro becomes an absolute game-changer. Instead of manually digging through databases for hours, you can just ask the AI for the latest judgments on granting leave under Order 7 Rule 14. Draft Bot Pro will instantly scan, analyse, and hand you the most current and authoritative precedents, making sure your arguments are always sharp, relevant, and built on the latest judicial thinking.

Curable Defects vs. Fatal Errors

Through their rulings, judges have also drawn a practical line in the sand between procedural hiccups that can be fixed (curable defects) and mistakes that are fatal to your document's admissibility. Forgetting to list a document in your initial list, but quickly moving to correct the error with a good reason, is often treated as a curable defect.

On the other hand, trying to introduce a vital document late in the game, especially after issues have been framed, with no good explanation, is likely to be seen as a fatal error. The consequences of getting this wrong are severe. High Courts report that a staggering 22% of appeals stem from trial court mistakes on document admissibility under this very rule. These errors frequently lead to cases being sent back for re-trial, adding an average of 18-24 months to the litigation lifecycle. You can explore more about the impact of such procedural issues on the Indian legal system. This statistic alone should be a stark reminder to get your document production right from day one.

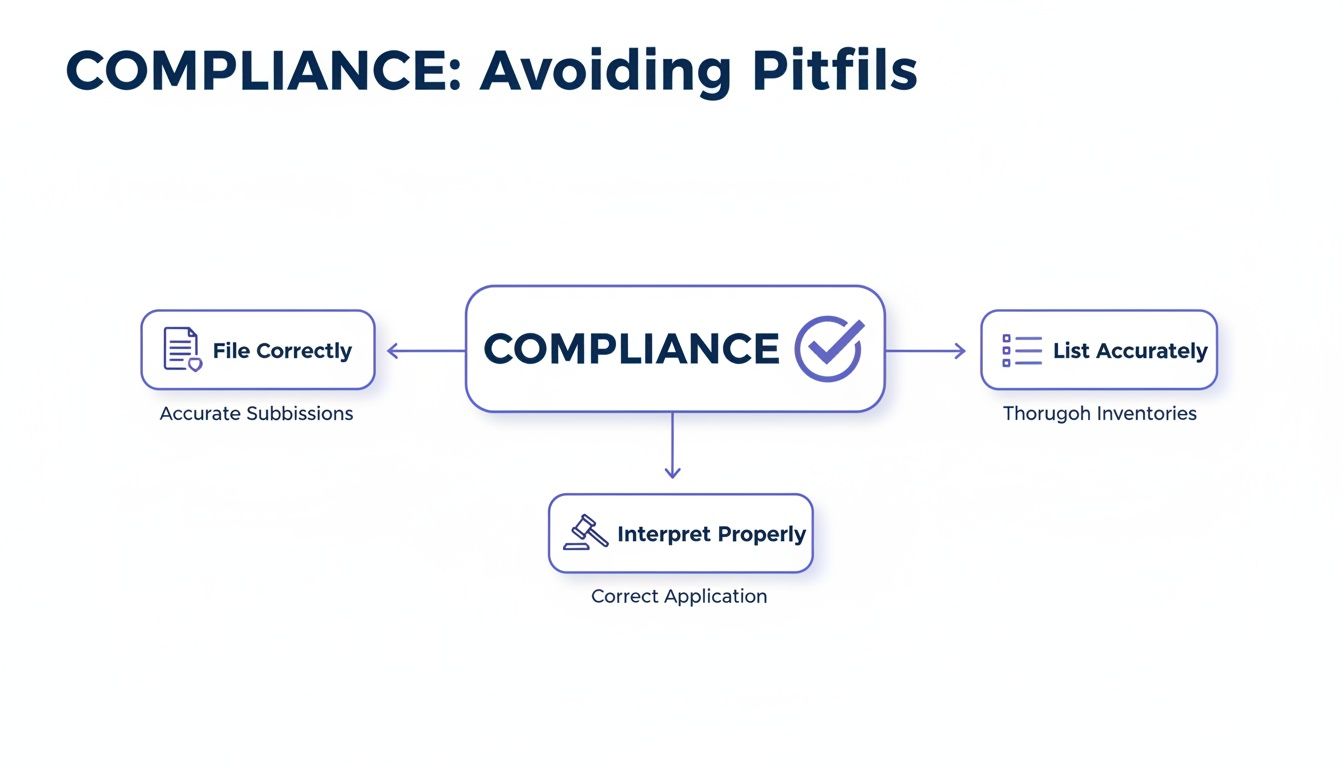

Common Pitfalls and Best Drafting Practices

Knowing the text of Order 7 Rule 14 is one thing; navigating it in the real world is another. More than a few solid cases have stumbled at the first hurdle, not because of weak arguments, but because of simple, avoidable procedural mistakes. These aren't just minor typos; they are cracks in your foundation that a sharp opponent will exploit.

The most common mistakes often seem trivial. Forgetting to attach a document you’ve mentioned in the plaint. Describing an email vaguely in your list. Misunderstanding what "relying upon" a document actually means in practice. Each slip-up creates a vulnerability, potentially leading to a judge refusing to look at your most crucial piece of evidence later on.

Identifying and Avoiding Frequent Errors

The goal isn't just to dump a pile of documents on the court. It’s about creating a clean, transparent record from day one. You need to be methodical to maintain the procedural integrity of your plaint.

Here are the three classic blunders I see time and again:

The Omission Error: This is the most basic, yet most damaging, mistake. You spend a paragraph in your plaint detailing a key agreement, but then completely forget to file it or even include it in your list. It’s a self-inflicted wound.

The Vague Listing Error: Simply writing "various emails" or "correspondence" just won't cut it. Each document needs a description specific enough for the court and the defendant to know exactly what you're talking about.

The Misinterpretation Error: There's a huge difference between a foundational document you must file upfront and a surprise document you plan to whip out during cross-examination. Confusing the two is a strategic disaster waiting to happen.

For a broader perspective, it's always a good idea to stay sharp on the fundamentals, which are covered well in this guide on how to file court documents.

A Practical Guide to Compliant Drafting

Avoiding these traps comes down to one thing: discipline. You need a system. Every time you mention a document in your plaint, you must immediately cross-check it against your list of documents to be filed. It’s a simple self-audit, but it’s incredibly effective.

Insights: Automating Compliance with Draft Bot ProLet's be honest, manually checking every single averment against a growing list of documents is tedious and a recipe for human error. This is where legal AI like Draft Bot Pro is a game-changer. It can analyse your draft plaint and case notes, then automatically generate a compliant list of documents. It makes sure every piece of evidence you're relying on is properly flagged and included, turning a high-risk manual chore into an automated safeguard.

For instance, if your plaint says, "The defendant admitted to the outstanding amount in an email dated 15th March 2023," your personal checklist must confirm that this specific email is attached and clearly described in your filing. You can build better drafting habits by reviewing our guide on how to improve your legal drafting skills.

Do's and Don'ts for Order 7 Rule 14 Compliance

Here's a straightforward checklist to keep you on the right track, comparing best practices with the common mistakes that can get you into trouble.

Do | Don't |

|---|---|

List every single document you rely upon, even if it feels repetitive. | Use vague descriptions like "invoices" or "letters." Specify dates, parties, and the subject. |

Clearly state if a key document is not in your possession and who has it. | Forget to mention documents held by the other side or a third party. Transparency is key. |

Do a final review of the plaint with the sole purpose of matching every document mentioned to your filed list. | Assume your junior or clerk will catch all the errors. The ultimate responsibility is yours. |

Keep a separate, organised folder for documents you're holding back for cross-examination. | Mix your foundational evidence with the documents you plan to use to impeach a witness. |

By making these practices second nature, you stop just complying with Order 7 Rule 14 and start using it. You're building a stronger, more transparent, and far more persuasive case from the moment you file.

How Order 7 Rule 14 Interacts with Other CPC Provisions

A true mastery of Order 7 Rule 14 requires understanding that it never operates in a vacuum. Think of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) as a complex machine; each rule is a gear that must mesh perfectly with the others. If you don't appreciate these connections, the entire litigation process can grind to a halt.

This rule’s most direct and consequential relationship is with Order 7 Rule 11 (Rejection of Plaint). A major failure to comply with Rule 14—like not filing the core documents a suit is based on—can give the court grounds to reject the plaint outright. This isn't just a minor setback; it's a fatal blow delivered at the earliest stage.

The Plaintiff and Defendant Documentary Framework

The CPC creates a wonderfully balanced system for documentary evidence. While Order 7 Rule 14 lays out the plaintiff's initial duty, its direct counterpart is found in Order 8 (Written Statement). Specifically, Order 8 Rule 1A imposes a nearly identical obligation on the defendant, requiring them to produce all documents they rely upon when filing their written statement.

Together, these rules ensure both parties lay their documentary cards on the table right from the get-go. This symmetry prevents "trial by ambush" from either side. It gives the court a complete picture of the evidence, which paves the way for a much more efficient framing of issues and, ultimately, a speedier trial. For a closer look at the procedural steps that follow, you might find our guide on affidavits under CPC in India helpful.

Connecting Initial Filings to Trial Stages

The ripple effects of compliance (or non-compliance) with Order 7 Rule 14 extend deep into the trial itself. Its provisions are tightly linked with Order 13 (Production, Impounding and Return of Documents), which governs how documents are formally presented and admitted into evidence during the trial proceedings.

Here's the catch: if a document wasn't filed with the plaint as required by Rule 14, a party can't just casually produce it at the trial stage under Order 13 without first getting the court's permission. This shows how an initial procedural slip-up directly ties a litigant's hands when it comes to presenting evidence later on. The very first step of filing is intrinsically linked to the final stages of proof.

This simple map highlights that compliance isn’t a one-time act but a continuous process, demanding diligence from the moment of filing right through to judicial interpretation.

Insights: Strategic Procedural Mapping with AIBuilding a cohesive litigation strategy means mapping out these procedural dependencies from day one. It's not enough to know one rule in isolation; you have to anticipate how it will interact with others down the line. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro is exceptionally useful here. Its memo generation feature can analyse your case facts and create a procedural roadmap, highlighting the critical links between Order 7 Rule 14 and other provisions like Order 8 and Order 13. This ensures you build a case strategy that accounts for the entire CPC framework, not just isolated rules.

Common Questions Answered

When you're dealing with the nuts and bolts of the Civil Procedure Code, a few practical questions always pop up, especially around procedural rules like Order 7 Rule 14. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones I hear from junior lawyers and even seasoned practitioners.

What If I Find a Key Document After I've Already Filed the Suit?

This happens more often than you'd think. You file the plaint, and then a crucial piece of evidence surfaces. Are you out of luck? Not necessarily.

You can't just slide it into the record, though. The right to produce it isn't automatic. You’ll need to file a separate application asking the court for its leave (which is just a fancy legal word for permission).

In that application, you have to show "sufficient cause"—basically, a really good reason—for why you couldn't file it with the plaint in the first place, even when you were being careful. It's then up to the judge to decide whether your reason is good enough to allow the document on record.

Can I Just File Photocopies Instead of the Originals?

The golden rule in evidence law is that originals are king. But for practical purposes, the CPC does allow you to file copies along with your plaint.

There’s a catch, of course. You must be ready to produce the original documents for the court's inspection whenever it asks. This usually happens before or at the time of the settlement of issues, when the court is finalising the points of dispute.

Is a Wrong Decision on This a Ground for Appeal?

Absolutely. If you believe a trial court made the wrong call on a document under Order 7 Rule 14, it can definitely be a point you raise in an appeal.

For instance, if the court unfairly refused your application to bring a late document on record, or if it wrongly allowed your opponent to file something late without a valid reason, you can argue this was a mistake. The key is to show that the court's decision led to a miscarriage of justice.

Insights: AI as a Training ToolFor law students and young advocates just starting out, getting a firm grip on these procedural details is what separates the good from the great. It's not just about knowing the rule; it's about understanding the exceptions and how a judge might exercise their discretion. That's where cases are often won or lost. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can act as a powerful training partner. A student could mock-draft a plaint, and the AI can generate a compliant document list, highlighting potential omissions. This practical, hands-on learning builds the muscle memory needed for flawless compliance in a real-world setting.

How Can Legal AI Help Get This Right?

This is where modern tools can really give you an edge. Think of something like Draft Bot Pro as a smart assistant or a practice simulator.

A law student could, for example, use the AI to mock-draft a plaint for a hypothetical case. Then, they could ask it to spit out a checklist of all the documents they'd need under Order 7 Rule 14 based on the facts they've pleaded. This creates an immediate, practical link between the story you're telling in the plaint and the evidence required to back it up. It’s a fantastic way to build good habits and internalise compliance long before you step into a real courtroom.

Draft Bot Pro is an innovative AI-powered legal assistant designed to help Indian lawyers and law students create accurate legal documents and conduct in-depth research efficiently. Trusted by thousands, it's the most verifiable and affordable legal AI built by lawyers, for lawyers. Learn more at https://www.draftbotpro.com.