A Complete Guide to Section 353 of IPC for Legal Professionals

- Rare Labs

- 3 days ago

- 16 min read

Section 353 of the Indian Penal Code is all about protecting public servants. Think of it as a legal shield that makes it a crime to assault or use criminal force against a government official who is just trying to do their job. This law is crucial for keeping public order and making sure the government can function without its officers being intimidated or physically harmed.

Decoding the Shield for Public Servants

Picture a tense situation: a police officer is trying to control a chaotic crowd, or a tax official is carrying out a legitimate raid. These public servants are often in the line of fire, and their ability to do their duty is fundamental to a functioning society. Section 353 of the IPC was drafted specifically for these moments.

This law goes deeper than just punishing a simple assault. It zeroes in on the intent behind the act. The real target here is any action meant to scare, stop, or get in the way of a public official while they're on the clock. Without this legal backstop, the entire machinery of governance could grind to a halt under the threat of violence.

The Purpose Behind the Provision

At its heart, Section 353 is about upholding the authority and dignity of the state itself. It ensures that every public servant, from a municipal worker cleaning the streets to a high-ranking officer in a government department, can do their work without being bullied or coerced. In essence, an attack on a public servant on duty isn't just an attack on an individual—it's treated as an assault on the state.

The law is straightforward: anyone who assaults or uses criminal force against a public servant to stop them from doing their job can face up to two years in prison, a fine, or both. For a deeper dive, you can explore a detailed legal analysis of the provision to understand its full scope.

A Quick Overview

To really get a handle on Section 353, it’s best to break it down into its core parts. For any law student or legal professional dealing with a case under section 353 of the IPC, understanding these fundamentals is the first and most important step.

A quick summary can help put the key components into perspective.

Section 353 IPC At a Glance

Component | Description |

|---|---|

The Accused | Any person who commits the act. |

The Act (Actus Reus) | An assault or the use of "criminal force" is committed. |

The Victim | The person must be a "public servant" as defined under Section 21 IPC. |

The Context | The public servant must be acting in the "execution of his duty." |

The Intent (Mens Rea) | The act must be done with the intent to prevent or deter the public servant from performing their duty. |

This table lays out the essential ingredients that the prosecution needs to prove for a conviction under this section.

InsightsTiming and context are everything when it comes to Section 353. The key phrase is 'in the execution of their duty'. If the official is off-duty, or if they are acting beyond their legal authority, this section might not even apply. This highlights just how critical it is to establish a direct link between the assault and the official's duties at that specific moment.

For legal professionals, navigating the complexities of drafting charge sheets or bail applications for these cases demands absolute precision. This is where an AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a real game-changer. By analysing the specific facts of your case, it helps generate accurate documents that tick every box and address all the essential elements of Section 353.

Unpacking The Essential Elements of The Offence

To make a charge under Section 353 of the IPC stick, the prosecution can’t just make a vague accusation. They have to prove three specific ingredients. Think of it like a three-legged stool—if even one leg is missing, the entire case collapses.

For lawyers, breaking down these elements is day-one strategy. Whether you're building a case for the prosecution or punching holes in it for the defence, it all starts here.

Pillar 1: The Victim Must Be a Public Servant

First things first, who was the target? The offence only applies if the person assaulted was a ‘public servant’. This isn't just a narrow term for police officers. The definition under Section 21 of the IPC is incredibly wide, covering everyone from judges and municipal corporation employees to government doctors and officials carrying out their duties.

But it gets more specific. The public servant must have been acting in the 'execution of their duty' when the incident occurred. They need to be performing a task that’s lawfully part of their job. So, a police officer settling a personal argument while off-duty doesn't get protection under this section.

The law isn't just about protecting an individual; it's about shielding the very function of the state they represent.

Pillar 2: The Act of Assault or Criminal Force

The second pillar is the physical act, the actus reus. The accused must have either committed an 'assault' or used 'criminal force'. These two terms have very precise meanings in the law and are not interchangeable.

Assault (Section 351 IPC): This is all about making someone believe they're about to be harmed. Picture someone balling up their fist and lunging at a tax official during a raid. Even if the punch never lands, that aggressive gesture, causing the official to fear immediate harm, is enough to qualify as assault.

Criminal Force (Section 350 IPC): This is where physical contact actually happens. Shoving a civic worker who’s trying to tow an illegally parked car, or grabbing a constable’s uniform to resist arrest—these are textbook examples of using criminal force.

Without one of these actions, a Section 353 charge has no legs. Shouting insults or just standing in the way might be an offence under a different law (like Section 186 IPC for obstruction), but it won't meet the higher bar for this one.

Pillar 3: The Intent to Deter From Duty

Here’s the heart of the matter—the mens rea, or the guilty mind. This is often the trickiest part to prove and where most legal battles are fought. The assault or force must have been used with the specific intent to stop or discourage that public servant from doing their job.

This element is what separates a deliberate act of defiance from a simple, unrelated scuffle. If you accidentally bump into an officer in a crowded street, there’s no intent. But if you shove that same officer to help your friend escape custody, the intent becomes crystal clear. The goal was to interfere with their duty.

InsightsThe prosecution carries the full burden of proving this intent. Courts don't just take their word for it; they scrutinise everything—what was said, what was done, and the entire context of the situation—to figure out what was going on in the accused's mind. The key question is always: Was this act done specifically to stop the public servant from performing their official duty?

This focus on intent is what makes Section 353 so serious. It’s not just about an attack on a person; it's an attack on the rule of law and the administration of justice.

For legal professionals, getting the articulation of these elements right in your drafts is everything. This is where modern tools can give you an edge. For instance, AI-powered platforms like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. You can upload your case file and instruct the AI to draft a charge sheet or bail plea that systematically addresses each pillar—the victim’s status, the physical act, and the evidence of intent. It helps ensure your document is not just well-written, but legally airtight.

Navigating Punishment and Legal Procedures

Knowing the ingredients of an offence under Section 353 of the IPC is one thing; understanding the real-world consequences is another entirely. Once the prosecution has made its case, the conversation shifts to punishment and the maze of legal procedures that every case must navigate. The penalties and the procedural rules attached to this section really drive home just how seriously the law takes any interference with a public servant's duty.

A conviction here isn't a slap on the wrist. The law lays down a punishment of imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both. This gives the court a fair bit of leeway to decide on a sentence that fits the crime, taking into account how serious the assault was and the specific circumstances of the whole incident.

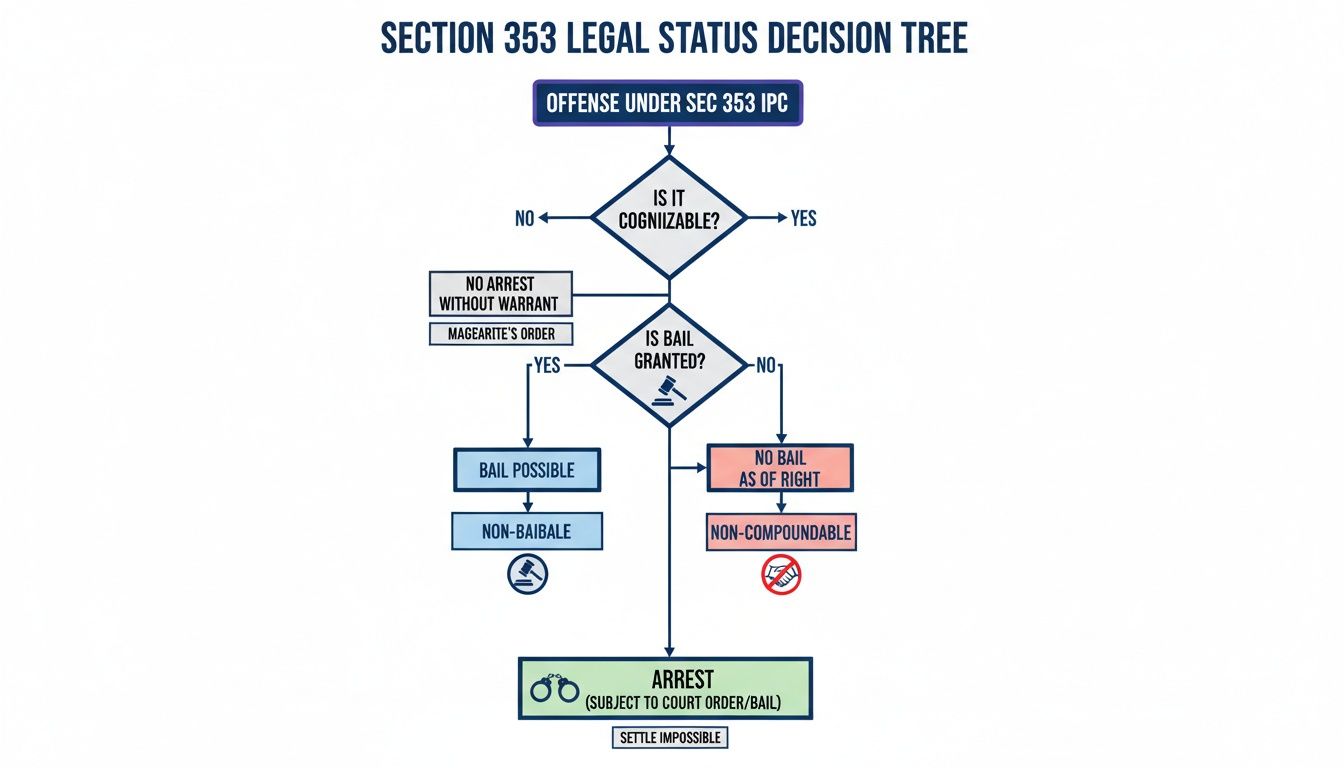

The Procedural Trio: Cognizable, Non-Bailable, Non-Compoundable

Beyond the sentence itself, it's the procedural classification of the offence that dictates how everything unfolds, from the moment of arrest to the final verdict. Section 353 IPC carries three critical labels that every lawyer and law student needs to have down pat. Each one has a massive impact on the accused.

These aren't just legal terms to memorise for an exam. They are the gears that turn the criminal justice machine, defining police powers, the accused person's liberty, and whether the case can be quietly settled.

Cognizable Offence: In simple terms, this means the police can arrest a suspect without a warrant. This power is usually reserved for more serious crimes, and it lets law enforcement act fast to stop any further trouble or obstruction. For Section 353 IPC, this gives police pretty wide authority to make an arrest if they have good reason to, without being held to a strict timeline. As explained in this detailed legal breakdown of arrest timelines, investigations can run for up to 90 days after the FIR is filed before an arrest might even happen.

Non-Bailable Offence: This is where a lot of people get tripped up. "Non-bailable" doesn't mean you can't get bail at all. It just means bail isn't an automatic right; it's entirely at the discretion of the court. The accused has to file a proper bail application, and the judge will weigh things like the seriousness of the offence and whether the accused is a flight risk before making a decision.

Non-Compoundable Offence: This one is crucial. It means the case cannot be settled privately between the parties. The public servant who was assaulted can't just "drop the charges" if they come to an agreement with the accused. The thinking here is that an offence against a public servant isn't just a personal matter—it's an offence against the state itself, and the state has an interest in seeing it through to the end.

The Evolving Legal Landscape

Like any area of law, this isn't set in stone. Legislatures are always looking to amend laws to keep up with what society needs. For example, the state of Maharashtra has looked at proposals to hike up the punishment for Section 353 offences, which points to a growing trend of getting tougher on people who attack public officials.

This just goes to show why legal professionals have to keep a close eye on state-specific amendments. What's true in one state might not be in another, and that can completely change how you approach a case.

InsightsThese procedural labels are the absolute foundation of any criminal litigation strategy. For a defence lawyer, the "non-bailable" tag immediately sets up the first major hurdle: securing bail. For the prosecution, the "cognizable" and "non-compoundable" status gives them a solid platform to push the case forward without worrying about outside pressure or backroom deals.

Keeping up with these procedural quirks and any legislative shifts is non-negotiable. This is where a legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a real game-changer. Lawyers can use it to instantly pull up state-specific amendments or find the latest case law on bail for non-bailable offences. It ensures your arguments are always sharp, current, and built on solid ground.

Distinguishing Section 353 From Related Offences

In the intricate web of the Indian Penal Code, it's easy to get tangled up in sections that seem to overlap. For any legal professional, drawing a sharp line between these provisions isn't just an academic exercise—it's a critical skill. This is especially true when dealing with offences against public servants, where Section 353 of the IPC can be confused with its close cousins, Section 186 and Section 332.

The differences in the act, intent, and consequences are vast. Picking the right charge can genuinely make or break a case.

This visual decision tree neatly lays out the strict procedural classifications for an offence under Section 353 of the IPC.

As the flowchart shows, an offence under this section is cognizable (so police can arrest without a warrant), non-bailable (meaning bail is purely at the court's discretion), and non-compoundable (it can't be settled out of court between the parties).

Section 353 vs. Section 186: The Line Between Obstruction and Assault

The most common point of confusion is telling the difference between a simple obstruction and an actual assault. Section 186 of the IPC deals with voluntarily obstructing a public servant while they are doing their job. The key distinction here is the complete absence of force.

Think about a tax officer trying to enter a building for a raid. If someone just stands in the doorway, verbally refuses entry, or even parks a car to block the path, that's obstruction under Section 186. There’s no physical contact, no threat of harm.

But what if that person shoves the officer? Or raises a hand as if to strike them? That's when the situation escalates. The moment assault or criminal force enters the picture, the offence moves squarely into the territory of Section 353. The first is a much lesser offence, carrying a lighter punishment of up to three months in prison.

Section 353 vs. Section 332: When Assault Becomes Hurt

While Section 353 covers assault or the use of criminal force, Section 332 of the IPC takes things a step further. This section kicks in when someone voluntarily causes hurt to a public servant to stop them from doing their duty. The crucial word here is "hurt," which Section 319 of the IPC defines as causing bodily pain, disease, or infirmity.

Let's go back to our tax officer scenario. If the person blocking the way doesn't just shove the officer (Section 353) but actually punches them, causing a bruise or some other injury, the offence becomes far more serious. The act has now resulted in actual physical harm.

This jump in severity is reflected in the punishment. A charge under Section 332 is much graver, with a potential prison sentence of up to three years. For a deeper dive into how the law treats similar acts of grievous hurt, it's worth checking out our guide on Section 325 IPC punishment for a useful comparison.

To make these distinctions even clearer, let's break them down side-by-side.

Comparison of IPC Sections 353, 186, and 332

Provision | Core Act (Actus Reus) | Required Intent (Mens Rea) | Punishment | Nature of Offence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Section 186 IPC | Voluntarily obstructing a public servant. | To obstruct the public servant in the discharge of their public functions. | Up to 3 months imprisonment or a fine, or both. | Non-cognizable, Bailable. |

Section 353 IPC | Assaulting or using criminal force against a public servant. | To deter or prevent that person from discharging their duty as a public servant. | Up to 2 years imprisonment or a fine, or both. | Cognizable, Non-bailable. |

Section 332 IPC | Voluntarily causing hurt to a public servant. | To deter or prevent that person from discharging their duty or in consequence of anything done in the lawful discharge of such duty. | Up to 3 years imprisonment or a fine, or both. | Cognizable, Non-bailable. |

The progression is crystal clear when you see it laid out like this: Section 186 is about interference without force; Section 353 involves force or the threat of it; and Section 332 is triggered when that force results in actual injury. For lawyers, framing the charge accurately based on the evidence of force and injury is absolutely fundamental to a successful prosecution or defence.

Learning From Landmark Case Law

The black-and-white text of a statute gives you the rules of the game. But it’s in the courtroom, through landmark judgments, that you learn how the game is actually played. These rulings breathe life into Section 353 of the IPC, carving out its real-world boundaries and clarifying its scope. For any of us in the legal profession, these judgments aren't just history lessons; they are strategic blueprints for building a case that wins.

Judicial interpretations are where the rubber meets the road. Time and again, courts have had to step in and define what "in the execution of his duty" really means in a practical sense. They've laid down how to prove the crucial element of intent, and they’ve drawn the line between a genuine act of criminal force and what amounts to just a heated argument. This body of precedent is the bedrock of any solid legal argument you'll ever make on this section.

Defining "Execution of Duty" and Intent

One of the most fought-over questions in a Section 353 case is whether the public servant was genuinely acting within their lawful duty when the incident happened. The courts have been crystal clear on this: the official can't be off on a personal frolic or acting beyond their legal authority. The duty they are performing must be lawful and directly tied to their official responsibilities at that very moment.

Likewise, proving the accused's intent—the mens rea—is everything. The prosecution has to show, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the assault or use of force was a deliberate act to stop the official from doing their job. This is where evidence becomes the star of the show. Judges will meticulously scrutinise the accused's actions and words to figure out what was going through their mind. An accidental bump or a spontaneous outburst, without that clear intent to obstruct, just won't cut it. You can dive deeper into judicial reasoning in our review of the top 8 landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India.

A Real-World Example of Conviction

Cases that end in a conviction are powerful teachers. They show us exactly how the different elements of Section 353 click together in a way that persuades a court. It’s here that we move from abstract legal theory to the very real, tangible consequences of the law.

Take the 2014 conviction in Sessions Trial No.78/495 of 2004 in Gaya, Bihar. Here, the appellants—Akhilesh Kumar, Navlesh Kumar, and Pawan Kumar—were handed two years of rigorous imprisonment. What did they do? They assaulted an Amin, Anand Mohan Srivastava, on September 18, 2002, while he was carrying out duties ordered by the court. This case is a perfect illustration of how a direct assault on an official performing a specific, court-mandated task creates an open-and-shut case. To get a better feel for the court's thinking, you can read the full case summary.

InsightsUsing precedents effectively is more than just name-dropping old cases; it’s about telling a strategic story. When you find a judgment where the facts mirror your own case, you can show the court a clear path. You’re essentially arguing, "The same thing happened here, and this is how it was decided." This builds a persuasive narrative that can significantly strengthen your position, whether you're aiming for a conviction or an acquittal.

Differentiating Force From Verbal Threats

Another critical distinction that case law has sharpened over the years is the line between actual criminal force and simple verbal abuse. Courts have consistently held that while shouting abuses at an official is certainly wrong, it doesn’t, by itself, make for a crime under Section 353. The law demands an act of 'assault' or 'criminal force'.

So, what constitutes an 'assault' under the IPC? It requires a gesture or action that makes someone reasonably fear they are about to be harmed. A fiery verbal tirade, on its own, won't meet that standard. It’s only when that tirade is paired with a threatening physical act—like a raised fist or a sudden lunge—that it crosses the line into a potential Section 353 offence. This judicial clarity is vital; it prevents the law from being misused to escalate minor arguments that lack any real physical threat.

Navigating this vast ocean of case law can feel like a herculean task. This is where modern legal tools give you a serious edge. A legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro, for example, is a game-changer for this kind of work. Its advanced research feature lets you instantly find the most relevant and recent High Court and Supreme Court judgments related to section 353 of ipc. It turns hours of painstaking manual research into a task of minutes, making sure your arguments are always backed by the strongest, most current precedents available.

Turning Theory into Action with AI-Powered Legal Drafting

Knowing the black-letter law of Section 353 IPC is one thing; translating that knowledge into a document that persuades a judge is another thing entirely. This is where theory meets practice, and it's precisely this gap that modern tools are now bridging for legal professionals.

A strong bail application or a watertight charge sheet hinges on articulating the offence's core elements with absolute clarity. Any ambiguity or oversight can crumble your case. For instance, a bail plea needs to convincingly argue against the non-bailable nature of the charge, while a charge sheet must be crafted to leave no room for doubt.

How AI Can Sharpen Your Drafting

This is exactly where an AI legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro can become a game-changer. Instead of staring at a blank page, you can upload a case brief and have the AI generate a meticulously structured draft in moments. This frees you and your team from the drudgery of clerical work to focus on what truly matters: strategy.

InsightsThe advantage isn't just about drafting faster. It's about achieving greater accuracy and strategic depth. By handling the foundational drafting, Draft Bot Pro lets lawyers dedicate their mental energy to refining arguments, predicting counter-moves, and ultimately building a more formidable case.

Section 353 IPC, a holdover from our colonial past, is still invoked in thousands of cases every year. As the new BNS 2023 comes into force, staying on top of the details is critical. For legal teams, AI tools can instantly verify crucial points through PDF chats—an invaluable function. For a junior lawyer tackling their first Section 353 draft, AI assistance is a lifeline in a field where cases are reportedly rising by 16% annually, yet conviction rates often hover around a mere 20-30%.

Understanding how technology can be applied in various professional and even academic contexts, like using AI to help with homework, provides a broader perspective. The integration of AI into the legal field points towards a smarter, more efficient way of working. You can explore this further by reading about using AI to draft legal documents.

Frequently Asked Questions

When you're dealing with a specific provision like Section 353 of the IPC, a lot of practical questions pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common ones that lawyers and law students often grapple with.

What's The Main Difference Between Section 353 and Section 186 of The IPC?

Think of it this way: Section 186 is about obstruction, while Section 353 is about attack. The real dividing line is the element of force.

Section 186 of the IPC covers voluntarily obstructing a public servant in their duties. This could be something as simple as blocking a doorway or refusing to move your vehicle. It doesn't have to be physical. But Section 353 kicks in the moment you introduce 'assault or criminal force' to stop that officer. It's the act of physically deterring them, or making them believe you're about to, that elevates the offence. That physical element is what makes a Section 353 charge so much more serious.

Is an Offence Under Section 353 IPC Bailable?

In a word, no. An offence under Section 353 IPC is non-bailable. This is a crucial point to remember. It means the accused can't claim bail as a matter of right.

Getting bail is entirely up to the court's discretion. A judge will look at the whole picture—the severity of the assault, the context of the incident, and other facts—before deciding. This classification really underscores how seriously the law treats any attack on a public servant trying to do their job.

Can Just Yelling at an Officer Lead to a Section 353 Charge?

Generally, no. Mere verbal abuse, however foul, isn't enough to make a case under Section 353. The section's language is very clear: it requires either 'assault' or the use of 'criminal force'.

InsightsRemember, 'assault' under the IPC isn't just the physical contact itself. It's any gesture or action that makes someone reasonably fear you're about to use criminal force on them. So, if those insults are backed up by a raised fist, a sudden lunge, or any other threatening physical act, then you've crossed the line into Section 353 territory. Without that physical element, the act might fall under other, less severe provisions, but not this one.

How Can Draft Bot Pro Help With a Section 353 IPC Case?

For a practitioner, this is where a tool like Draft Bot Pro becomes incredibly useful, especially when handling a Section 353 of IPC case. Its legal research function is a game-changer, letting you pull up the latest and most relevant judgments from the Supreme Court and various High Courts in seconds.

But it's more than just research. You can upload your case brief and have the AI generate a solid bail application, one that's specifically structured to argue for discretion in a non-bailable offence. It's also brilliant for drafting the formal charges themselves, ensuring they are precise, well-supported, and backed by current case law. It's all about saving time while boosting the quality of your legal documents.

Ready to see how much more efficient your practice can be? Join the 46,000+ legal professionals who already rely on Draft Bot Pro. Check out how our AI-powered drafting and research tools can transform your workflow at https://www.draftbotpro.com.