IPC Section 356 A Guide to Assault and Theft Laws in India

- Rare Labs

- Dec 23, 2025

- 17 min read

When you think of street crime, what comes to mind? A purse being snatched, or a mobile phone being ripped out of someone's hand? These aren't just simple thefts; they're aggressive acts that violate a person's safety. This is precisely what Section 356 of the Indian Penal Code is designed to tackle.

It specifically zeroes in on the crime of using assault or criminal force while attempting to steal something a person is physically wearing or carrying.

Decoding the Law on Snatch-and-Grab Theft

While some laws can feel a bit theoretical, IPC Section 356 is rooted in a very real, very frightening experience. It's not just about the loss of property. The law recognises that the moment a thief uses force against a person, the crime escalates. It becomes an attack on their physical well-being.

Let's break it down with a couple of scenarios to see the difference:

A pickpocket skilfully lifts a wallet from someone's bag in a crowded bus. This is a classic case of theft, falling under Section 379.

A mugger shoves a pedestrian against a wall and tries to wrench their backpack off their shoulders. This is a completely different ball game. The shove and the struggle are the key ingredients that bring it under Section 356.

The real purpose of this law is to add a crucial layer of protection for personal safety. It acknowledges that trying to steal a phone is one thing; assaulting someone to do it is far more serious.

IPC Section 356 At a Glance

For legal professionals juggling multiple cases, getting to the heart of a provision quickly is non-negotiable. This table breaks down the essential components of Section 356 for easy reference.

Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

Offence | Assault or criminal force in an attempt to commit theft of property worn or carried by a person. |

Cognizable/Non-Cognizable | Cognizable. This means the police can make an arrest without a warrant. |

Bailable/Non-Bailable | Bailable. The accused has a right to be released on bail. |

Triable By | Any Magistrate. |

The punishment prescribed under the Indian Penal Code for an offence under Section 356 is imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both. For a deeper dive into the statutory text, you can find more insights on the law at devgan.in.

What This Means in Practice

InsightsOne of the biggest challenges for a prosecutor in a Section 356 case is proving the 'attempt'. Think about it: in a completed theft, the stolen item is your proof. But in an attempt, the entire case often hangs on demonstrating the accused's intent through their actions. That act of grabbing, pulling, or pushing isn't just a detail—it's the core piece of evidence that elevates the charge.

For young lawyers and law students, understanding this distinction is what separates a well-drafted charge sheet from a weak one. You have to articulate not just the intent to steal, but the act of force that accompanied it.

This is where modern tools can be a game-changer. An AI-powered legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be incredibly helpful here. It analyses the facts of your case and suggests the right language and sections, ensuring that critical elements like 'criminal force' are precisely and correctly stated right from the start. It's like having a seasoned paralegal on hand, helping you build a stronger, more robust case with greater efficiency.

The Four Essential Ingredients of an Offence

To successfully prosecute someone under IPC Section 356, your case needs to be built on four solid pillars. Think of it like a legal recipe—miss even one ingredient, and the final dish, a conviction, will fall flat in court. The prosecution has to prove each of these elements beyond a reasonable doubt to turn an accusation into a legally sound case.

Let's break down exactly what those are, moving from legal theory to how they play out on the street.

Ingredient 1: The Act of Assault or Criminal Force

First and foremost, there has to be either assault or the use of criminal force. This is the key difference between a snatching offence under Section 356 and a stealthy theft like pickpocketing. The law here isn't just worried about the stolen item; it’s focused on the aggressive act against the victim.

Under the Indian Penal Code, 'criminal force' means intentionally using force on someone without their consent, either to commit another crime or just to cause injury, fear, or annoyance. It could be a violent shove, a forceful grab of a handbag, or a sharp tug on a gold chain. Even a slight push can qualify if the criminal intent is there.

Ingredient 2: The Clear Intent to Commit Theft

The second ingredient is all about the accused's state of mind, what we lawyers call mens rea. The prosecution must show that the assault or criminal force was used for one specific reason: to commit theft. A random shove in a crowded market is one thing, but if that shove was part of a deliberate move to steal something, that's what Section 356 is all about.

This is often the trickiest part to prove. An accidental bump that happens to knock a wallet out of someone's hand is worlds away from a calculated grab. Intent is usually figured out by looking at the person's actions. Was their hand reaching for a pocket? Did they make a lunge for a phone? These actions paint a clear picture of what they were really trying to do.

InsightsA very common defence tactic in these cases is to attack the idea of intent. The defence lawyer will often argue that any physical contact was just an accident or a misunderstanding, not a planned attempt to steal. This is exactly why strong witness testimony and clear evidence of the forceful act are so crucial for the prosecution to establish the necessary mens rea.

Ingredient 3: Property Worn or Carried by the Victim

The third pillar gets specific about the target. For Section 356 to kick in, the property has to be something the victim is either wearing (like a necklace, watch, or earrings) or carrying (like a purse, mobile phone, or a backpack). This detail is critical because the law is designed to protect people from being attacked for the things they have on their person.

It really highlights how personal and invasive this crime is. It’s not just about losing property; it's about the violation of a person's immediate physical space and safety.

Ingredient 4: The Action Must Be an Attempt

Finally, it’s absolutely vital to remember that IPC Section 356 is fundamentally about the attempt to commit theft using force. The crime is considered complete the very moment the assault happens during the attempt. It doesn't matter if the thief actually got away with the item or not.

Successful Snatching: If someone yanks a chain and it breaks off, they can be charged under Section 356 (for the assault) and also Section 379 (for the theft itself).

Failed Snatching: If they yank the chain but it doesn't break and they run off, the offence under Section 356 is still complete. Why? Because the forceful attempt was made.

Getting these nuances right when drafting an FIR or a charge sheet is crucial. A legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a massive help here. By analysing the facts of an incident, it helps legal professionals make sure all four of these ingredients are clearly laid out, ensuring the charges perfectly match the specifics of what happened.

Distinguishing Between Theft, Robbery, and IPC 356

When you're dealing with the Indian Penal Code, offences involving property can feel like a maze of overlapping sections. For any lawyer, getting the charge right is paramount, and this means understanding the fine lines between Section 356 (Assault in attempt to commit theft), Section 379 (Theft), and Section 392 (Robbery).

It almost always boils down to one critical factor: the presence and degree of force.

While all these offences involve dishonestly taking property, the way it's done changes everything. Think about it – a stealthy pickpocket, a snatch-and-run artist, and a violent mugger who hurts someone aren't the same. The law treats them differently, and for very good reason. Each poses a different level of threat to us and our sense of safety.

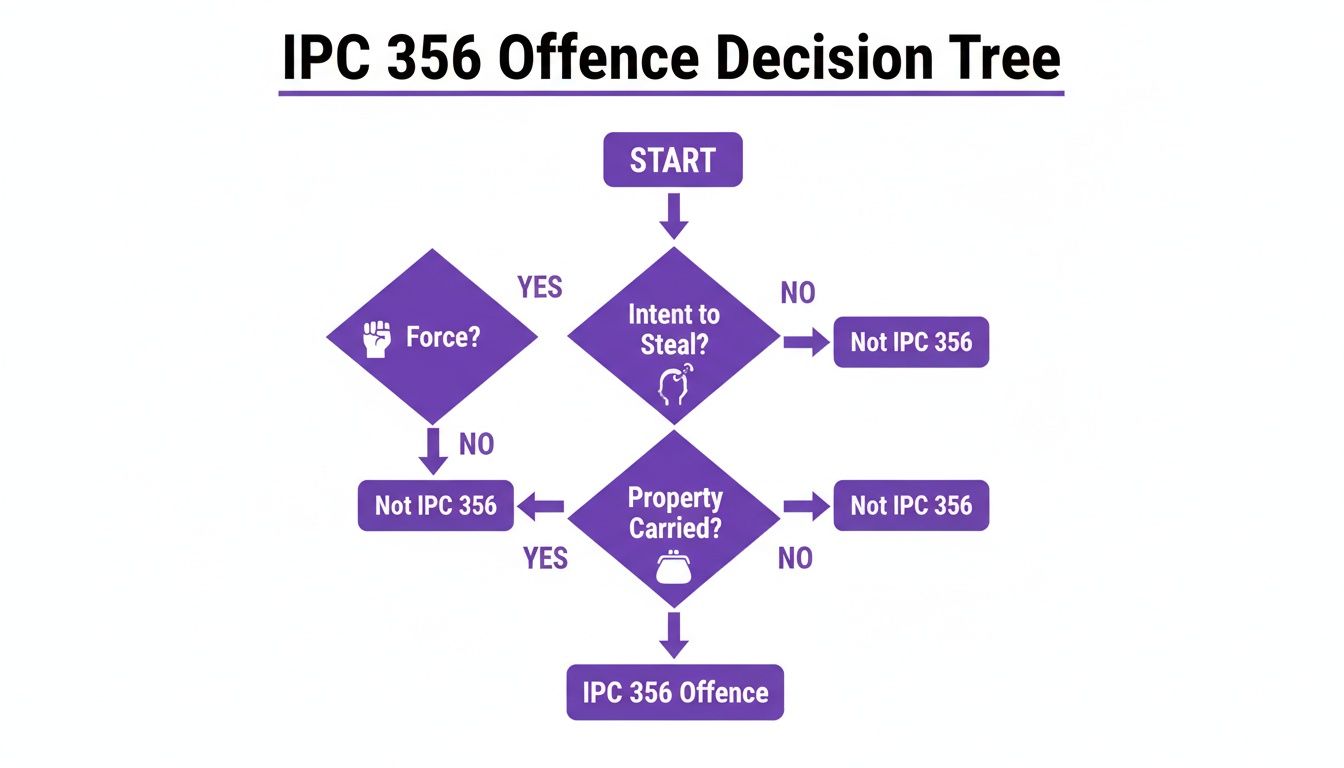

This decision tree breaks down the logic of when an act becomes an offence under IPC 356.

As you can see, the offence is a specific cocktail of intent to steal, the use of actual force, and the fact that the property is being carried by the victim at that moment.

The Spectrum of Force

The simplest way to grasp the difference is to see these offences on a spectrum. The more violence involved, the more severe the punishment.

Section 379 (Theft): This is your starting point. It’s the dishonest removal of movable property without consent. The key here is stealth, not aggression. A pickpocket who lifts a wallet without the victim feeling a thing is a classic example. No force is used against the person.

Section 356 (Assault in Attempt to Commit Theft): This is the next level up. The offender uses assault or criminal force specifically in an attempt to steal something a person is wearing or carrying. Think of a chain-snatcher who yanks a necklace but fails to break it and flees. Even though the theft didn't happen, the use of force in the attempt is enough to trigger this section.

Section 392 (Robbery): This is the heavy hitter. Robbery is essentially theft supercharged with immediate violence or the threat of it. The force isn't just part of an attempt; it's the tool used to achieve the theft by causing or threatening death, hurt, or wrongful restraint. A mugger who pulls a knife and demands your phone is committing robbery.

Why Correct Classification Is Everything

Getting these classifications right isn't just a legal technicality; it has massive real-world consequences. It affects police statistics, public perception of safety, and where law enforcement directs its resources.

A fascinating analysis of Delhi Police data, for instance, revealed a troubling pattern. Many snatching cases, which are textbook examples of street crimes under IPC Section 356, were being logged as simple theft under Section 379. This administrative sleight-of-hand painted a rosier, but false, picture of street crime rates, which could seriously skew policy decisions. You can read more about how this was uncovered in the Hindustan Times report.

InsightsEver wonder why a prosecutor might charge under Section 356 instead of robbery, even when things got a bit violent? It often comes down to the evidence. Proving the "fear of instant death or hurt" required for robbery can be tough. If the evidence for force is solid, but proving the victim was in life-threatening fear is shaky, a prosecutor might go for a Section 356 charge to secure a conviction they're more confident in winning.

Here’s a table that lays out the key differences at a glance.

Comparing Theft-Related Offences in the IPC

This table makes it easier to compare the essential elements and punishments for these closely related sections.

Legal Provision | Core Element | Use of Force | Maximum Punishment |

|---|---|---|---|

Section 379 | Dishonest taking of movable property | None (stealth) | 3 years imprisonment or fine, or both |

Section 356 | Assault or criminal force in an attempt to steal property being carried | Force is used, but theft may not be completed | 2 years imprisonment or fine, or both |

Section 392 | Theft committed by causing or threatening instant death, hurt, or wrongful restraint | Violence or threat of violence is used to commit the theft | 10 years rigorous imprisonment and fine |

As you can see, the use of force is the dividing line, directly impacting the severity of the potential sentence.

For lawyers and law students, mastering these distinctions is non-negotiable. It shapes how you draft an FIR, what evidence you lead, and the arguments you build in court. And if you're working on a case involving dishonest intent but not necessarily theft, you may find our guide on criminal misappropriation under IPC Section 403 useful.

This is precisely where tools like Draft Bot Pro become a game-changer. By feeding in the facts of an incident, the AI can analyse the elements—especially the nuances of force—and suggest the most accurate sections to apply. This ensures you start on the right foot, preventing your case from getting derailed by an incorrect charge down the line.

How Landmark Rulings Have Shaped Section 356

While the Indian Penal Code gives us the black-and-white text of the law, it’s the courtroom where the real picture gets filled in. The lifeblood of IPC Section 356 comes from the landmark judgments of the Supreme Court and various High Courts. They've been absolutely crucial in defining its scope and showing how abstract legal terms apply to real-world street crime.

Think of these rulings as a practical guide for lawyers and judges, ensuring the law is applied consistently and fairly. They get into the nitty-gritty of what actually counts as 'criminal force' and what separates simply planning a crime from making a concrete 'attempt'. Understanding this body of case law isn't just an academic exercise; it’s a necessity for building a watertight prosecution or a rock-solid defence.

Clarifying Criminal Force and Intent

One of the biggest questions that comes up with Section 356 is the threshold for "criminal force." Is a slight touch enough? What if the victim barely even noticed? The courts have consistently said that the degree of force is far less important than the intention behind it.

A great example is the case of Phulabai v. State of Maharashtra. Here, the court drove home the point that even minimal force, when combined with the intent to commit theft, is enough to bring Section 356 into play. The act of snatching a 'mangalsutra' from a woman's neck was a clear-cut application of criminal force aimed at theft.

This precedent is so important because it shifts the focus away from how badly the victim was hurt and onto the accused person's mindset and actions. The real core of the offence is the aggressive act during the attempt, not necessarily the outcome or the level of violence.

Another key case, Sita Ram v. State of Rajasthan, helped draw a clearer line around the element of 'attempt'. The court ruled that you need an overt act that goes beyond just preparing. Simply following someone with the idea of stealing from them isn't enough; there has to be a direct move towards the crime, like reaching out to grab their property.

Judicial Observations on Modern Street Crimes

As society evolves, so does crime. Courts have had to interpret Section 356 in the modern context of rampant urban crimes like mobile phone snatching. The legal principles established in older cases about chain or purse snatching are now regularly applied to these newer scenarios.

InsightsYou can see a clear trend in the judiciary: a stricter stance on street crimes falling under IPC Section 356. Courts are increasingly acknowledging the fear and public disruption these acts cause. Because of this, judges often point out that even a failed attempt can have a huge psychological impact on the victim and the community, which justifies a strong legal response. This view reinforces the idea that the 'attempt' itself is a serious offence.

This evolving interpretation makes sure the law stays relevant. The focus remains on protecting people from aggressive attempts to steal their personal belongings, whether it’s a traditional piece of jewellery or a brand-new smartphone. For anyone interested in how our judiciary approaches foundational legal principles, checking out the top 8 landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India gives fantastic insight into judicial reasoning.

The Role of AI in Case Law Analysis

For any legal professional, staying on top of all these judicial interpretations is a massive task. We've all been there—sifting through decades of case law, trying to find that one perfect ruling to support an argument. It can be incredibly time-consuming. This is exactly where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro changes the game.

Instead of losing hours in a law library or digging through online databases, you can just input the facts of your case. Draft Bot Pro can instantly scan thousands of judgments and pinpoint the most relevant precedents for IPC Section 356. It can highlight key observations from judges and help you understand how courts have handled similar situations in the past. This lets you build a more persuasive, evidence-backed argument with incredible speed and accuracy.

Practical Guidance and AI-Powered Legal Drafting

Moving from the black letter of the law to the realities of the courtroom demands more than just knowing the statute. For lawyers handling cases under IPC Section 356, success is built on a foundation of meticulous drafting, a sharp understanding of bail and sentencing, and the foresight to dismantle defence arguments before they're even made. Let’s get into some actionable strategies for building a solid case.

It all starts with the First Information Report (FIR). When you're drafting an FIR for a Section 356 offence, vague language is your enemy. It's not enough to just say a theft was attempted. You need to paint a picture. Use active, descriptive words like "yanked," "shoved," "grabbed," or "wrenched" to show the court exactly how the physical confrontation happened.

This precision must carry through to the charge sheet. Every single element of the offence has to be clearly laid out and backed by solid evidence. This means witness statements confirming the use of force, medical reports detailing any injuries, and a clear narrative that connects the accused's actions to the intent to steal property from the victim. A well-built charge sheet closes loopholes and leaves no room for doubt.

Crafting Compelling Legal Documents

A strong Section 356 case lives and dies in the details of its paperwork. Here's where to focus your attention:

Detail the Force: Be specific about the force used. Was it a sudden pull from behind? A direct push to throw the victim off balance? These specifics are what make the charge stick.

Establish Intent: Explicitly connect the assault to the attempted theft. For example, "The accused forcefully grabbed the victim's wrist for the purpose of snatching the mobile phone she was holding."

Specify the Property: Always name the item that was the target of the theft. Crucially, you must state that it was being worn or carried by the victim at that exact moment.

InsightsA common weakness in Section 356 cases is a hazy description of the incident, which defence lawyers love to pick apart. By focusing on a clear sequence—the approach, the use of force, and the immediate attempt to steal—you create a powerful narrative that can withstand the pressures of trial.

Leveraging AI for Enhanced Efficiency

This level of detailed drafting is critical, but let's be honest, it takes a lot of time. This is exactly where legal AI tools like Draft Bot Pro come into play. You can input the basic facts of the case and get a solid first draft of an FIR or charge sheet that already includes the necessary legal structure and language. This frees you up to focus on fine-tuning the story and strengthening the evidence.

For instance, Draft Bot Pro can take your case summary and suggest the most precise legal terms to describe the criminal force, ensuring all four ingredients of IPC Section 356 are covered. It can also perform lightning-fast research to pull up relevant case law that supports your arguments on bail or sentencing. What used to be hours of painstaking work can now be done in minutes.

Navigating Bail and Sentencing

Since an offence under IPC Section 356 is bailable, the accused has a right to seek bail. At the bail hearing, the prosecution’s job is to highlight any aggravating factors, such as the accused's criminal history or the risk of witness intimidation. The defence, of course, will lean on the bailable nature of the offence and the accused's ties to the community.

When it comes to sentencing, the court weighs several factors: the amount of force used, any injuries sustained, the value of the property involved, and the offender's background. Prosecutors should push for a sentence that reflects the severity of the assault, while defence lawyers will point to mitigating factors to argue for a lighter penalty.

AI is becoming a powerful ally here, too. Lawyers are increasingly asking if they can use AI to draft legal documents, and the answer is a firm yes. Platforms like Draft Bot Pro can help you prepare bail applications or sentencing submissions by finding and weaving in relevant case law, making sure your arguments stand on a strong foundation of judicial precedent.

As these tools become more integrated into our work, practical guidance isn't just about drafting; it's also about understanding the broader impact of technology. Exploring resources on understanding AI in legal advertising can offer a wider view. By embracing these tools, legal professionals can work smarter, build stronger cases, and ultimately deliver better results for their clients.

The Big Shift from IPC to Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

If you're a legal professional in India, you've likely spent years, if not decades, memorising the Indian Penal Code. So, the shift to the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) is more than just a legislative update—it’s a fundamental rewiring of your professional muscle memory.

One of the key changes you'll need to get a handle on is the re-shuffling of section numbers. Let’s take a classic provision like IPC Section 356, which deals with assault or criminal force during a theft attempt. Under the BNS, that number now means something entirely different. Section 356 of the BNS now covers the offence of defamation.

So, Where Did the Old Section 356 Go?

Don't panic. The substance of the old law hasn't vanished; it's just moved house.

The offence of using assault or criminal force while trying to snatch property a person is carrying is now found under Section 122(2) of the BNS. The core principle is the same: punishing the forceful attempt to steal personal property. This is all part of a larger, ambitious project to modernise and streamline India's criminal laws, making the code more logical and shedding some archaic baggage.

InsightsThis transition period is a double-edged sword. On one hand, you've got to unlearn section numbers that are practically ingrained in your DNA. It's a real challenge. On the other hand, it's an opportunity to get ahead. The lawyers who dive in and master the new BNS structure first will have a serious advantage in their drafting, arguments, and overall case strategy. It's time to hit the books again.

For context, the new BNS Section 356 now consolidates what used to be IPC Sections 499 and 500 (defamation). The punishment remains largely the same: up to two years in prison, a fine, or the newly introduced community service. If you're looking for more details on these changes, you can find a good overview of the restructuring of important IPC sections here.

How to Navigate This Shift Without Tearing Your Hair Out

Keeping track of these changes manually is a recipe for disaster. One slip-up, one old section number in a new draft, and you could face procedural errors that compromise your entire case.

This is where legal AI tools like Draft Bot Pro become indispensable. Think of it as your personal paralegal, one that's already fluent in the BNS. Instead of flipping through books or running uncertain web searches, you can rely on its up-to-date database to instantly pinpoint the correct BNS provision for any offence. It ensures your FIRs, charge sheets, and applications are accurate from the get-go, letting you focus on strategy instead of getting bogged down in clerical work.

FAQs About IPC Section 356

When you're dealing with the Indian Penal Code, some sections seem to overlap at first glance. Section 356 is a classic example, often raising questions for both seasoned lawyers and law students trying to get a handle on the fundamentals. Let's clear up some of the most common points of confusion.

Core Legal Distinctions

What’s the main difference between IPC 356 and simple theft under IPC 379?Think of it this way: the core difference is the presence of force against a person. A pickpocket who stealthily lifts a wallet is committing theft under Section 379. There's no confrontation, no physical struggle.

But Section 356 kicks in the moment there's an 'assault or criminal force' used in the attempt to steal something a person is carrying. It's about the act of physically trying to snatch a chain, grab a purse, or wrestle a phone away. The law sees this as a more serious offence because it directly endangers personal safety, moving beyond a simple property crime.

Can someone be charged under both Section 356 and Section 379 for the same act?Absolutely, and it happens all the time. It’s not a case of double jeopardy but rather charging for different aspects of the same event. The police might file an FIR under both sections to cover all bases.

Section 356 covers the assault during the attempt to steal. If the thief succeeds and actually gets away with the property, Section 379 can be added to cover the completed theft.

Procedural Aspects and Application

Is an offence under IPC Section 356 bailable?Yes, an offence under Section 356 is classified as a bailable offence. This is a crucial point for any defence counsel—it means the accused has a right to be released on bail. It is, however, also a cognizable offence, which gives the police the power to make an arrest without a warrant.

Does a simple push while grabbing a purse count as 'criminal force'?Almost certainly, yes. The threshold for what constitutes 'criminal force' under the IPC isn't sky-high. Any intentional use of force, however slight, to commit an offence can meet the definition.

A quick shove, a tug on a sleeve, or a grab at a bag is more than enough. If the force was intended to make the theft easier, it will almost always satisfy this element of the offence.

InsightsFor practising lawyers, nailing these distinctions is everything. Whether you're framing charges for an FIR or arguing for bail, how you describe the force used can make or break your case. This is where getting the details right from the start is non-negotiable.

This is exactly the kind of detailed work where an AI legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. It helps you dissect the facts of a case to make sure every legal element is precisely identified and articulated in your documents, cutting down on time and avoiding costly mistakes.

Tired of second-guessing legal nuances and spending hours on drafting? Draft Bot Pro is the AI-powered legal assistant built by Indian lawyers, for Indian lawyers. Create spot-on legal documents, run verifiable research, and get your workflow in order in minutes. Join over 46,000 legal professionals and see the difference at https://www.draftbotpro.com.