Criminal Misappropriation IPC A Practical Guide to Section 403

- Rare Labs

- Dec 22, 2025

- 16 min read

When you hear "criminal misappropriation," what comes to mind? It’s a specific kind of property offence defined under Section 403 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), and it boils down to the dishonest conversion of movable property for your own use.

The twist here is that the initial act of taking the property isn't necessarily wrongful. The crime is born from a later, dishonest decision to keep it.

Unpacking The Concept Of Criminal Misappropriation

Let's use a simple, real-world scenario. Say you find a wallet lying on a cafe table. At that moment, you haven't committed a crime. The law presumes you might be looking for its owner. You're just a finder of lost property.

The crime happens the second you decide to make that wallet yours. You pocket the cash, throw away the ID, and start using the credit cards. That mental shift—from innocent finder to dishonest keeper—is the absolute heart of criminal misappropriation. The offence isn't about the finding; it’s about the dishonest intention that follows.

The Foundation of Section 403 IPC

Criminal misappropriation is a key pillar in the IPC's approach to economic offences, tackling situations where property ends up in someone's hands lawfully but is then kept unlawfully. It's a crucial part of India's criminal justice system, which you can learn more about by exploring statistics on crime in India.

This section plugs a vital gap. It punishes the wrongful retention of property that doesn't quite fit the classic definition of theft, where the initial taking must be dishonest.

Insights from Legal AI

Teasing out the nuances of intent and possession in these cases can be tricky. This is where a legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can really help. By feeding it the facts of your case, it can sift through precedents to find similar scenarios where "innocent possession turning dishonest" was the central issue. For a lawyer, this is a massive time-saver. It helps you quickly find relevant case law to build a stronger, more informed argument, whether you're prosecuting or defending.

Key Takeaway: The essence of criminal misappropriation is the subsequent dishonest intention. The initial possession is often innocent or neutral. The crime is committed only when the person decides to treat the property as their own, thereby depriving the rightful owner.

A Quick Summary

To make this crystal clear, let's break down the essential components of the offence.

Key Elements of Criminal Misappropriation (Section 403 IPC)

Element | Description |

|---|---|

Movable Property | The offence applies only to movable property, which includes things like cash, vehicles, jewellery, or any tangible item that can be moved. |

Initial Possession | The property must initially come into the accused's possession innocently, through chance, or without any criminal intent. |

Misappropriation | The accused must misappropriate the property or convert it for their own use. |

Dishonest Intention | The conversion or misappropriation must be driven by a dishonest intention to cause wrongful gain to oneself or wrongful loss to another. |

Understanding these four pillars is the first step to mastering Section 403 and distinguishing it from other property-related offences.

Breaking Down The Ingredients Of Section 403

To really get to grips with a charge of criminal misappropriation under the IPC, you have to break Section 403 down into its core components. Think of it like a recipe. If you're missing even one ingredient, the final dish – in this case, a successful prosecution – simply won't work. The prosecution carries the entire burden of proving every single one of these elements beyond a reasonable doubt.

Let's walk through each ingredient, step-by-step, to see exactly when finding something crosses the line and becomes a criminal offence.

1. The Property Must Be Movable

First things first, and this one is pretty straightforward: the nature of the property itself. Section 403 only ever applies to movable property. This is basically anything that isn't bolted down to the earth, like land or buildings.

So, what are we talking about?

Things like cash, jewellery, or a wallet you find on the street.

A vehicle, whether it's a car or a motorcycle.

Livestock or other animals.

Gadgets like phones and laptops.

If the argument is over immovable property, like a house or a plot of land, you're in the wrong ballpark. That dispute falls outside criminal misappropriation and will be dealt with under different civil and criminal laws. Getting this initial filter right is crucial for applying the correct section of the law.

2. The Accused Must Convert It For Their Own Use

This is where the rubber meets the road—the physical act of the crime. It's not enough for the accused to just have the property. They have to actually misappropriate it or convert it to their own use. In simple terms, they start acting like the property is theirs, doing things with it that completely disregard the real owner's rights.

"Conversion" is a broad term. It doesn't just mean selling the item. It could be any act that denies the owner their rightful claim. For instance, if you find a lost dog and decide to keep it as your new family pet, you've just converted it for your own use. Even finding a friend's textbook and lending it to someone else without asking them first qualifies as conversion.

Legal Insight: Think of the act of conversion as the outward sign of a dishonest mind. It’s the concrete action a court can actually see and judge. Without some act of conversion, there's no offence, no matter what dishonest thought might have flickered through someone's head.

3. Initial Possession Must Be Innocent

This is probably the most critical element that sets criminal misappropriation apart. The property has to have come into the accused person's hands innocently. The initial moment of taking possession wasn't wrongful. It could happen by pure chance, like finding a lost wallet, or by mistake, like getting an extra item in a delivery package.

The IPC itself gives a great illustration: If 'A' finds a government promissory note on the road that belongs to 'Z', and 'A' knows it's Z's but picks it up intending to sell it, that's theft. But, if 'A' finds the note, has no idea who the owner is, and only later gets the idea to sell it for his own gain, that's criminal misappropriation. The key difference is that the initial possession was completely innocent.

4. A Dishonest Intention Must Arise Later

The final, and often the trickiest, ingredient is the mens rea, or the guilty mind. A dishonest intention to misappropriate the property must pop up after the accused already has it. This specific "dishonest intention" is defined under Section 24 of the IPC as doing something to cause a wrongful gain to one person or a wrongful loss to another.

Of course, proving what was going on in someone's head is always a challenge. Courts have to infer this dishonest intent from the person's actions. Did they try to find the real owner? Did they hide the item away? Did they start using it openly as if they owned it? The fact that someone took no reasonable steps to return the property is often the most powerful evidence that a dishonest intention was formed later on.

Navigating these elements requires a sharp analysis of the facts. For legal professionals, a legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. By feeding in case details, the AI can conduct targeted legal research, digging up precedents where courts debated the fine line between an innocent find and a dishonest conversion. This helps you build a much stronger, more well-supported argument.

How Misappropriation Differs From Theft And Breach Of Trust

Ask any law student or even a seasoned lawyer, and they'll tell you that telling apart similar property offences can be a real headache. At first glance, criminal misappropriation under Section 403 of the IPC, theft (Section 378), and criminal breach of trust (Section 405) look almost interchangeable. But they aren't.

The legal distinctions are actually quite sharp, and getting them right is critical for framing charges correctly or mounting a solid defence. The secret is to look at three things: how the property was first obtained, when the dishonest intention kicked in, and the relationship between the people involved. Each offence has its own unique recipe of these elements, and understanding that is half the battle.

The Core Difference: Initial Possession

The biggest clue to telling criminal misappropriation apart from theft lies in how the accused first got their hands on the property.

In a classic theft, the act of taking is dodgy from the get-go. There's no innocent phase. The offender's intent is dishonest from the very beginning.

Criminal misappropriation, on the other hand, starts out innocently. The accused might find a lost wallet, receive a wrong UPI transfer, or come into possession of something without any initial plan to keep it. The crime only happens later, when they decide, "You know what? I'm keeping this."

Key Insight: The timing of the mens rea (the guilty mind) is everything. For theft, the dishonest mind is there before or during the taking. For misappropriation, the dishonest mind shows up after an innocent act of possession.

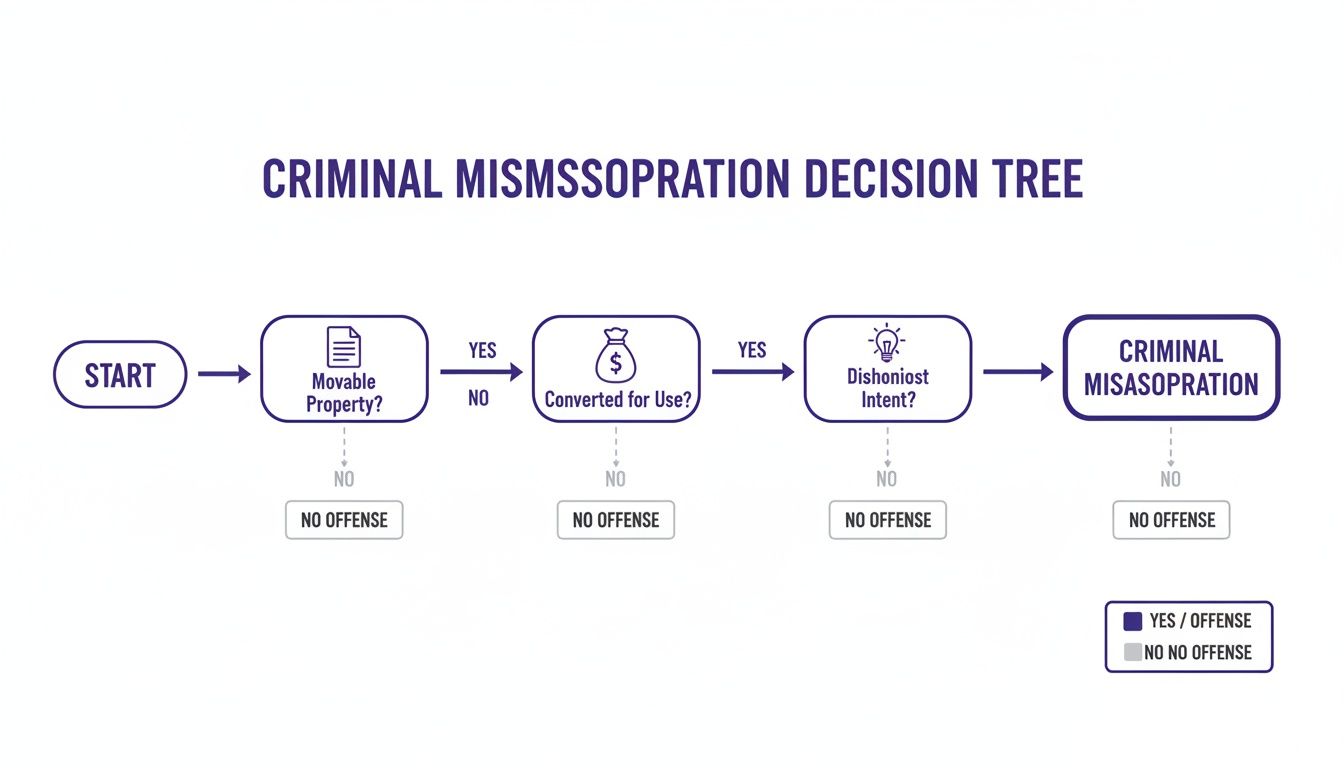

This flowchart can help you visualise how to pinpoint criminal misappropriation.

As you can see, the offence is only made out when you can tick all the boxes: it's movable property, it's been converted for personal use, and a dishonest intention developed after the person got hold of it.

The Element of Entrustment

Now, let's throw criminal breach of trust into the mix. This one has a special ingredient that sets it apart from both theft and misappropriation: entrustment.

Here, the property isn't just found or taken. It's deliberately handed over by the owner to the accused for a specific reason, based on a relationship of trust. Think of an employee entrusted with company cash, a warehouse owner given goods for safekeeping, or a trustee managing assets. The crime happens when that trusted person dishonestly uses the property for something other than what was agreed upon, shattering that trust.

A Comparative Look

To really nail down the differences, let's put these three offences side-by-side.

This table breaks down the essential ingredients that differentiate these closely related but legally distinct property offences.

Criminal Misappropriation vs Theft vs Criminal Breach of Trust

Basis of Distinction | Criminal Misappropriation (S. 403) | Theft (S. 378) | Criminal Breach of Trust (S. 405) |

|---|---|---|---|

Initial Possession | Starts innocently or by chance. The property comes into possession by mistake or is found. | Wrongful from the very beginning. The property is taken without the owner's consent. | Lawful and based on a relationship of trust. The property is willingly given to the accused. |

Dishonest Intention | Forms after the person has already taken possession of the property. | Exists from the start, at the exact moment the property is taken. | Develops after the property has been rightfully entrusted to the accused. |

Element of Trust | No pre-existing relationship of trust is necessary. | Trust is not a factor at all. | A relationship of trust and the act of entrustment are the core of the offence. |

Conversion/Taking | The property is converted to the accused's own use after an innocent possession. | The property is moved or taken out of the owner’s possession. | The property is dishonestly converted in direct violation of a specific instruction or law. |

This comparison makes it clear that while all three deal with movable property, the how and when of possession and intent lead to completely different legal outcomes. For example, punishments for criminal breach of trust are often harsher, reflecting the serious violation of a trusted relationship. If you're dealing with a case involving an employee, you might want to read our complete legal guide to Section 408 IPC, which covers criminal breach of trust by a clerk or servant.

Judicial Insights from Landmark Case Law

The law books give you the black-and-white rules, but it’s in the courtroom where these principles really come to life. For criminal misappropriation under the IPC, judgements from the Supreme Court and various High Courts have been absolutely critical in shaping how we understand this offence. These decisions bring much-needed clarity to abstract ideas like 'dishonest intention' and 'conversion', giving us a practical map for how Section 403 is applied in the real world.

Going through these landmark cases isn't just a stuffy academic task; it’s essential for anyone trying to get a real handle on the law's finer points. They show us how judges weigh evidence, what counts as a "reasonable step" to find a property's owner, and exactly where an innocent mistake crosses the line into a criminal act. If you're dealing with an allegation of criminal misappropriation, you simply can't afford to ignore this case law.

The Supreme Court on Dishonest Intention

One of the most important cases that really got to the heart of criminal misappropriation is R.K. Dalmia v. Delhi Administration. While the case itself was a complex web of charges, the Supreme Court's take on dishonest intention is still quoted constantly. The court drove home the point that dishonest intent is the absolute cornerstone of the offence and must be proven for a conviction under Section 403.

The ruling made it crystal clear: just having someone else's property for a bit isn't a crime. The offence only takes shape the very moment a person decides to use that property for their own gain, causing a wrongful loss to the person who actually owns it. This judgment set a high standard for the prosecution, forcing them to show a clear mental shift from innocent possession to a deliberate, dishonest act of conversion.

Judicial Insight: The Supreme Court has consistently said that the timing of the dishonest intention is what matters most. It's not about how you first came across the property, but the later decision to wrongfully keep it.

Clarifying ‘Conversion’ in State of Gujarat v. Jaswantlal Nathalal

The case of State of Gujarat v. Jaswantlal Nathalal offers a fantastic breakdown of what 'conversion' actually means in a criminal sense. Here, the court did a great job distinguishing a simple civil issue from a criminal offence. The takeaway was that not every broken promise or failure to return property automatically becomes criminal misappropriation.

The court explained that for an act to be a criminal 'conversion', there has to be a clear intention to treat the property as your own, completely disregarding the rights of the actual owner. This case helps us see that the accused's actions must be so at odds with the owner's rights that it's obvious they're trying to claim it for themselves.

Property-related offences are a huge part of the Indian legal landscape. In fact, crimes against property made up 23.3% of all cognizable crimes under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) registered across the country in 2023. You can dig deeper into these numbers and see how often these cases end up in court by checking out the latest data on property crime in India.

How a Legal AI like Draft Bot Pro Simplifies Case Law Research

Trying to stay on top of decades of judgements can feel like an impossible task. This is exactly where a legal AI called Draft Bot Pro becomes a game-changer. Instead of spending hours sifting through databases, you can just type in the facts of a specific criminal misappropriation scenario. The AI then instantly scans its massive library of case law to pull up the most relevant precedents. For example, let's say your case turns on whether the accused took "reasonable steps" to find the owner. Draft Bot Pro can immediately find judgments where courts have defined what 'reasonable' means in similar situations. This gives lawyers and students the power to build their arguments on a solid foundation of judicial precedent, which not only saves a huge amount of time but also seriously improves the quality of their work. You can learn more about these foundational cases by reading about the top 8 landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India.

It’s one thing to understand the legal theory behind criminal misappropriation, but what really hits home are the real-world consequences. The Indian Penal Code is crystal clear about the punishments for those found guilty, turning abstract legal concepts into tangible penalties. These punishments aren't just there to scare people off; they show just how seriously the law takes the dishonest use of someone else's property.

The standard penalty for criminal misappropriation under Section 403 is imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both. A judge has the room to decide what fits the crime, looking at things like the value of the property and how the accused behaved.

The Aggravated Offence Under Section 404

Now, the law gets even tougher when the property involved belonged to someone who has passed away. Section 404 of the IPC was drafted for this specific, and frankly, quite grim scenario. It acknowledges just how vulnerable property is in that window of time after a person's death and before the rightful heirs can take control.

This aggravated form of the offence comes with a much steeper price.

The prison sentence can go up to three years, and a fine is also mandatory.

If the offender was working for the deceased as a clerk or servant at the time of their death, the punishment gets even more severe, potentially leading to seven years behind bars.

This harsher penalty sends a strong message: the law is dedicated to protecting the assets of the deceased from anyone looking to take advantage of the grief and confusion that follows a death.

A Look at National Crime Patterns

Stepping back to look at crime statistics gives us a bigger picture of how property offences like criminal misappropriation play out across the country. The data often shows clear regional patterns, highlighting hotspots for economic crimes. For instance, data from 2009 showed that some areas were dealing with a disproportionate share of IPC crimes.

Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, for example, each accounted for about 9% of all reported IPC crimes nationwide. If we zoom in on the major cities, Delhi was at the top, reporting roughly 10.8% of total IPC crimes from 35 mega cities, with Bangalore following at 8.4%. You can dig deeper into these numbers in this official government report.

Insights for Legal Professionals: Keeping an eye on regional crime data can be a surprisingly strategic move. If you're handling a criminal misappropriation case in an area where it's common, you might find that local courts are more familiar with certain types of evidence or the modus operandi that frequently appear. This is where a legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can help by quickly analysing case law databases to spot regional precedents and judicial leanings, allowing lawyers to shape their arguments for the specific legal climate they're in. It’s about moving past a one-size-fits-all strategy to a more intelligent, geographically-aware approach to litigation.

Applying Legal Tech To Misappropriation Cases

When you're handling a case of criminal misappropriation under the IPC, precision is everything. From the first client meeting to drafting the complaint, framing charges, and finally arguing in court, every step has to be meticulous. In today's world, technology has become a powerful ally in the courtroom, helping us streamline these traditionally long-winded tasks. A legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can help at every stage, not just saving time but genuinely making a difference in the outcome of a case.

To build a solid misappropriation case, you have to nail every single essential ingredient of Section 403. It's not enough to just state the facts. You need to weave them into a compelling narrative backed by established legal principles and precedents. This is exactly where modern legal tech comes in, bridging the gap between raw case details and a polished, legally sound argument.

How Legal AI Changes The Game For Case Preparation

AI-powered legal assistants, like our very own Draft Bot Pro, are quickly becoming essential for legal professionals. Think of them not as a replacement, but as a force multiplier. These platforms are designed with the nuances of Indian law in mind, taking on the heavy lifting and automating the routine tasks where human error often creeps in.

Here’s a practical look at how Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer in a criminal misappropriation case:

Drafting Legal Notices and Pleadings: Forget starting from a blank page. You can use AI to generate a solid first draft of a legal notice or complaint in minutes. It ensures that all the crucial components of Section 403—from the dishonest intention to the act of conversion—are clearly and correctly articulated right from the start.

Laser-Focused Case Law Research: Instead of spending hours on manual keyword searches, you can simply input the specific facts of your case. The AI then gets to work, pulling up the most relevant and impactful case law that directly supports your arguments. To see this in action, check out our guide on using AI for Indian Penal Code (IPC) research-research).

Keeping Your Story Straight: AI tools are brilliant at maintaining consistency across all your documents and pleadings. This minimises the risk of tiny contradictions that could be exploited by the opposing counsel to weaken your case.

Insights for Modern PractitionersThe real magic of legal AI isn't just about speed; it's about strategic depth. When you automate the foundational work of drafting and research, you free up your mental bandwidth. This allows you to focus on what truly matters: building a rock-solid case strategy, anticipating the other side's moves, and preparing to advocate fiercely in the courtroom. It shifts your role from a legal labourer to a legal strategist.

Of course, beyond the courtroom, prevention is key. Understanding practical strategies for mitigating internal threats and ensuring human capital integrity is vital, especially for organisations looking to stop misappropriation before it even starts. Adopting modern tools gives you a clear competitive edge, empowering you to deliver better results for your clients with far greater efficiency.

Frequently Asked Questions About Criminal Misappropriation

To wrap things up, let's tackle some of the practical, real-world questions that often pop up around criminal misappropriation. These are the scenarios where the line between an innocent mistake and a criminal act can get a little blurry.

What’s The Difference Between Finding A Wallet And Committing A Crime?

This is a classic for a reason. Simply finding a lost wallet isn't a crime. The offence kicks in the moment you decide to dishonestly keep it for yourself, without making any real effort to find its owner.

Think about it: if the wallet has an ID card or a phone number inside, the law expects you to take reasonable steps to return it. If you ignore that, take the cash, and toss the wallet, your innocent act of finding something has crossed the line into criminal misappropriation. It all boils down to what a reasonable person would do in that situation.

Can A Business Partner Be Charged For Using Firm Property?

Absolutely, and it happens more than you'd think. While partners are obviously allowed to use company property for business, using it dishonestly for personal gain is a different story entirely.

For example, if a partner sells a company laptop and pockets the cash for a personal holiday without telling anyone, that's not authorised use. It's dishonest conversion. These cases often come down to the fine print in the partnership agreement and, crucially, proving that the partner acted with a dishonest mind.

InsightsProving dishonest intent is the central challenge in any criminal misappropriation case. Since intent is a state of mind, it is almost always proven through circumstantial evidence. A court will look at the accused's actions—or lack thereof—to infer their intentions. This is where a legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can help, by finding precedents where specific actions were deemed sufficient to prove a guilty mind.

How Is Dishonest Intention Proven In Court?

You can't see 'dishonest intention', so the prosecution has to prove it through the accused's behaviour and the surrounding circumstances. The court looks for actions that just don't add up if the person's intentions were honest.

This could include things like:

Hiding the found property from others.

Denying you have the item when the owner or police ask.

Trying to alter the property's appearance to disguise it.

Selling the item almost immediately without even trying to find the owner.

The lack of any reasonable effort to find the true owner is often the most powerful piece of evidence the prosecution will use to build its case.

Navigating these nuances requires a sharp legal eye. This is where a legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can give you an edge, quickly flagging relevant case law where similar actions were used to prove or disprove dishonest intent. It can take your case facts and instantly pull up precedents, helping you build a stronger, evidence-backed argument by showing how courts have interpreted similar conduct in the past.

At Draft Bot Pro, we provide AI-powered tools designed for Indian legal professionals to streamline research and drafting. Build stronger cases with instant access to relevant precedents and accurately drafted documents. Discover how we can support your legal practice at https://www.draftbotpro.com.