A Complete Guide to IPC Section 417 Cheating Laws

- Rare Labs

- 2 days ago

- 17 min read

When you hear "cheating" in a legal context, your mind probably jumps to complex financial scams or high-stakes fraud. But what about the simpler, everyday deceptions that still cause real harm? That's where Section 417 of the Indian Penal Code comes into play. It carves out a specific space for punishing what's known as 'simple cheating.'

This section deals with situations where someone is deceived into doing—or not doing—something that ends up harming their mind, body, reputation, or property. The crucial difference here is that no property is actually handed over as a result of the trickery.

Decoding Simple Cheating Under Section 417

Think of Section 417 as the foundational offence for deceit. It's not always about money changing hands; it's about the act of deception itself causing a tangible loss. The law is smart enough to recognise that harm isn't just financial.

The scope of damage under this section is surprisingly broad. It acknowledges that a lie or a trick can hurt people in many different ways, including:

Harm to Mind: Think of the mental anguish or emotional distress caused by a deliberate falsehood.

Harm to Body: This covers situations where deceit leads someone into physical danger or injury.

Harm to Reputation: A classic example is damaging someone's good name through a calculated deception.

Harm to Property: Even if no property is delivered, the act could cause damage to a person's existing assets.

You might be surprised to learn that this is one of the most commonly invoked fraud-related sections in Indian courts. In fact, data shows that cases under Section 417 often account for 15-20% of all fraud-related prosecutions in magistrate courts. This highlights just how critical it is for tackling everyday acts of deception. You can find more practical insights on how IPC Section 417 is applied in Indian courts on Lawtendo.

A Closer Look at the Offence

For any legal professional, getting the technical details of IPC Section 417 right is non-negotiable. The punishment is lighter than for more aggravated forms of cheating, which makes sense given the nature of the offence.

Insights Here’s the main takeaway: Section 417 punishes the act of cheating itself. This is different from more serious sections like 420, which punish cheating that specifically results in the delivery of property. This distinction is what makes Section 417 so versatile—it applies to a huge range of scenarios where deception is the core issue.

To give you a quick reference, here’s a table summarising the essential legal attributes of the offence.

IPC Section 417 at a Glance

This table breaks down the key characteristics of a Section 417 offence, from its bailable nature to the upcoming changes in the new criminal code.

Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

Offence | Simple Cheating |

Punishment | Imprisonment for up to one year, a fine, or both. |

Bailable/Non-Bailable | Bailable (the accused has a right to be released on bail). |

Cognizable/Non-Cognizable | Cognizable (police can arrest without a warrant). |

Future Legislation | Set to be replaced by Section 318 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), which introduces a much harsher penalty of up to three years imprisonment. |

Knowing these details is one thing, but applying them to a messy set of real-world facts is another.

How Draft Bot Pro Can Help Figuring out if a particular situation fits the bill for 'simple cheating' can be tricky. This is where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. You can input the case facts, and the AI will run a quick preliminary analysis against the legal ingredients of Section 417. It helps you instantly spot whether the core elements of deception and resultant harm are present, giving you immediate clarity before you dive deeper.

The Core Ingredients of a Cheating Offence

To get a handle on a charge under IPC Section 417, we first need to look under the bonnet and understand what 'cheating' actually is. Section 417 only lays out the punishment; the real action, the definition of the crime itself, is found in Section 415 of the Indian Penal Code. Think of it this way: you can't understand the penalty for a foul in football until you know what the rulebook considers a foul in the first place.

Every cheating offence stands on two legs: a physical act and a mental state. In legal speak, we call these the 'actus reus' (the guilty act) and 'mens rea' (the guilty mind). For a conviction to stick, the prosecution has to prove both of these beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Deceptive Act or 'Actus Reus'

The actus reus is the part of the offence you can see. It’s the concrete act of deception—the lie told, the truth hidden, or the misleading promise that gets the ball rolling. This is the action the victim sees and, crucially, acts upon.

Imagine you're buying a used car. The actus reus is the seller rolling back the odometer. It's the tangible, deceptive act that convinces you the car is in better shape than it really is. It’s the external action that creates the false belief.

For a proper legal footing, let’s look at the exact wording from the IPC that defines this act.

Section 415 IPC Cheating "Whoever, by deceiving any person, fraudulently or dishonestly induces the person so deceived to deliver any property to any person, or to consent that any person shall retain any property, or intentionally induces the person so deceived to do or omit to do anything which he would not do or omit if he were not so deceived, and which act or omission causes or is likely to cause damage or harm to that person in body, mind, reputation or property, is said to 'cheat'."

The key word here is "induces." The accused must have actively persuaded the victim to do something (or not do something) because of the deception. A simple misunderstanding doesn't cut it; there has to be a deliberate push from the accused.

The Dishonest Intention or 'Mens Rea'

This is where things get tricky. The mens rea is the dishonest intention that was buzzing around in the accused's mind right from the very beginning of the whole affair. It’s the most critical, and often the most difficult, element to prove.

Going back to our car analogy, the mens rea is the seller's knowledge, before you even showed up, that the odometer was faulty and their decision to use that fact to trick a buyer.

This timing is everything. If the intention to deceive pops up later—say, a person makes a promise in good faith but later finds they can't deliver—it’s usually just a breach of contract. That’s a civil matter, not a criminal offence under IPC 417. The prosecution’s job is to prove that the accused never planned to make good on their promise from the get-go.

Let's break it down with a couple of scenarios:

Criminal Cheating: A developer takes advance payments for flats, promising possession in two years. But here's the catch: he never even applied for the construction permits and used the money to fund a different venture. The dishonest intent was there from day one.

Civil Dispute: A supplier agrees to deliver goods but, due to unexpected factory lockdowns, fails to meet the deadline. His initial intention was honest. This is a classic breach of contract. This fine line is what separates criminal court from civil court, a distinction that's also vital in cases like criminal misappropriation under the IPC.

How Draft Bot Pro Identifies Mens Rea

Proving someone's state of mind from months or years ago is a massive challenge for any lawyer. The evidence is almost always circumstantial, buried in a mountain of emails, WhatsApp chats, and witness statements. This is where a sharp AI tool can give you a real edge.

Insights From Draft Bot Pro A specialised legal AI like Draft Bot Pro is built for this kind of detective work. You can feed it your entire case file—client notes, communication records, bank statements, you name it. The AI then meticulously sifts through everything to flag evidence that points towards (or away from) an initial dishonest intent.

For instance, it can quickly pinpoint:

Contradictory statements the accused made at different times.

Financial records showing the accused never had the means to fulfil their promise.

A pattern of making and breaking similar promises with other people.

By systematically connecting these dots, Draft Bot Pro helps you build a rock-solid argument around mens rea. It turns what is often a vague, hard-to-prove element into a structured, evidence-backed pillar of your case, letting you focus on strategy instead of getting lost in the paperwork.

Distinguishing Between IPC Sections 417 and 420

One of the most common trip-ups in criminal law is drawing the line between simple cheating and more serious forms of fraud. The distinction between IPC Section 417 and Section 420 is a make-or-break point for any prosecution, and getting it wrong can be fatal to a case.

At its heart, the difference is actually quite straightforward.

Think of it this way: Section 417 is like talking someone into stepping onto a dangerously rickety boat by lying about its safety. The harm is done—they've been deceived—but they haven't handed over any valuables. Section 420, on the other hand, is convincing them to give you their wallet before they get on that same boat. The key ingredient that changes everything is the delivery of property.

Section 417 casts a wider net, punishing the act of cheating itself, where the resulting damage could be to a person’s body, mind, or reputation. But Section 420 zooms in on a specific outcome: when that cheating dishonestly convinces the victim to deliver property or mess with a valuable security.

The Critical Role of Property Delivery

The whole legal argument pivots on one simple question: did the victim hand something over? If the deception only led to emotional distress, reputational damage, or even physical harm without any property changing hands, Section 417 is your go-to charge.

The moment the deceit results in a transfer of property—whether it’s money, goods, or anything of value—the offence gets a serious upgrade. This triggers the much tougher provisions of Section 420, which carries a hefty punishment of up to seven years behind bars.

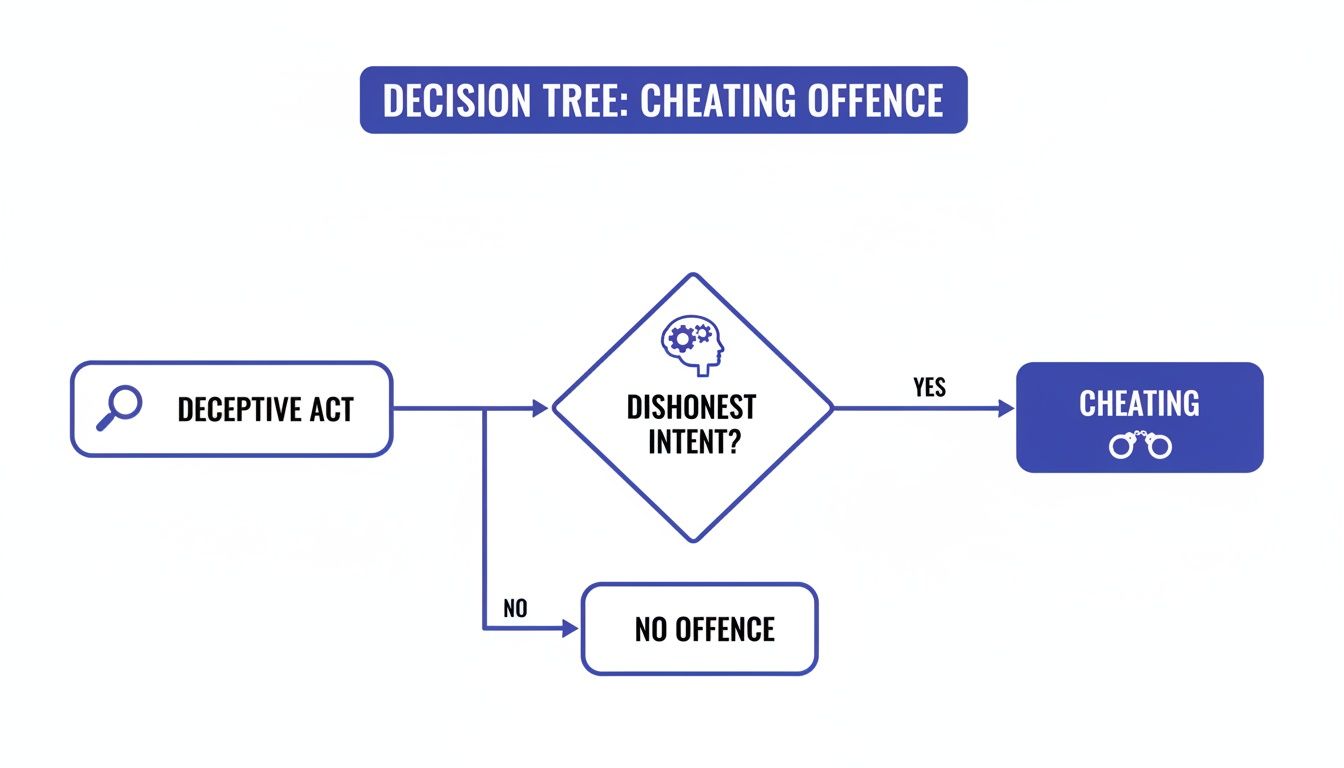

This flowchart breaks down the mental checklist for figuring out which cheating offence applies, based on whether there was a deceptive act and dishonest intent.

As you can see, a deceptive act plus dishonest intent always equals cheating, which is the foundation for an ipc section 417 charge.

Insights From Draft Bot Pro Making the wrong call between Section 417 and 420 can get your charges thrown out. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro is brilliant for this. Its research tools can instantly find landmark judgments that spell out this very distinction, giving you solid precedents to back up your choice and frame the charges correctly from day one.

To make things even clearer, let's put these two sections side-by-side.

Comparing Cheating Offences Under the IPC

Getting the nuances right is essential for any legal professional. This table lays out the key differences to help you correctly identify and frame charges related to cheating.

Provision | Core Element | Involves Property Delivery | Punishment | Common Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Section 417 | Simple cheating causing any form of harm (body, mind, reputation, property). | No, property is not delivered as a result of the deception. | Up to 1 year, a fine, or both. | Falsely promising marriage to induce a sexual relationship, causing mental anguish. |

Section 420 | Cheating and dishonestly inducing the delivery of property. | Yes, this is the essential ingredient of the offence. | Up to 7 years and a fine. | Selling a fake gold brick and inducing someone to pay for it. |

Choosing the right charge isn't just a technicality; it's fundamental to getting justice. The evidence you need, the arguments you'll make, and the potential sentence all hinge on this initial decision.

Mistakes in this area are all too common. Take Raj Kumar Sharma v. State of H.P. (2025), where charges under Section 417 were quashed because the prosecution couldn't prove that money was actually paid due to the alleged deceptive promise. It’s a perfect reminder of how crucial it is to prove every single element of the offence.

For a deeper dive into related offences, you might find our complete legal guide to Section 408 IPC helpful.

Landmark Cases That Shaped IPC Section 417

To really get a handle on IPC Section 417, you have to look beyond the textbook definition and step into the courtrooms where its true meaning has been hammered out over decades. The black-and-white text of the law comes to life through judicial interpretation, creating a rich history of precedents that guide how simple cheating cases are handled today. These key judgments draw the often-blurry line between a civil tiff and a criminal offence.

The story really starts back in the colonial era, with a case that’s still foundational. The Calcutta High Court's decision in R. v. Dabee Singh (1867) was a game-changer. It established that lying about your social status to trick someone could absolutely be considered cheating under Indian criminal law.

In this classic case, the accused brought two girls and passed them off as being from a much higher social standing than they actually were. He then arranged their marriages and pocketed monetary bonuses for the "service." The court convicted him, and in doing so, set a powerful precedent. You can find more on how this foundational precedent of Section 417 of IPC is discussed in Drishti Judiciary.

Early Precedents and Social Deception

The Dabee Singh ruling was massive. It made it clear that "harm" under the cheating definition wasn't just about losing money or getting physically hurt. The court recognised that deception causing damage to someone's reputation or social standing was just as punishable. This laid the groundwork for countless cases involving matrimonial fraud and misrepresentation of identity.

This early decision cemented the core idea of the offence: it’s the deceit itself and the harm it causes that matters, regardless of whether any property actually changed hands. That principle remains a cornerstone of IPC Section 417 jurisprudence even now.

Decisions made within these very walls over a century ago are still influencing legal arguments in modern courtrooms across India.

Modern Interpretations in Business and Contracts

Fast-forward to today, and the battleground for Section 417 has largely moved from social status to boardrooms and business deals. The Supreme Court has had to step in time and again to stop this criminal provision from being weaponised to settle what are, at their heart, purely civil disputes over broken contracts.

In recent cases like State of Gujarat v. Dilipsinh Kishorsinh Rao (2023), the apex court drove home a critical point: just because someone fails to keep a promise doesn't automatically make it cheating. The prosecution has to show solid proof that the accused had a dishonest intention (mens rea) right from the very beginning of the agreement. Without that proof of initial fraud, it’s a civil matter, not a criminal one.

Insights From Draft Bot Pro Staying on top of this ever-evolving case law is a real challenge. This is where a legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro shines. Its case law analysis feature doesn't just pull up these foundational cases; it also finds the most recent judgments that cite them. This lets you build layered, powerful arguments grounded in both classic precedents and the latest thinking from the Supreme Court and various High Courts.

The Nuance of "Promise to Marry" Cases

Another tricky area is where Section 417 is used alongside more serious charges in cases involving a "false promise to marry." The courts are extremely careful here, working to distinguish between a promise that was a lie from the start and one that was simply broken later on.

Take the recent case of Raj Kumar Sharma v. State of H.P. (2025). The Himachal Pradesh High Court discharged the accused of charges under Section 417. Why? The court pointed out that there was no real evidence in the FIR or the chargesheet to prove that money was actually paid because of the promise. That link is essential for the charge to stick. This judgment underscores just how much solid proof is needed to establish cheating in these emotionally charged situations.

This is exactly the kind of nuance Draft Bot Pro can help with. It can instantly analyse the facts of your case against thousands of similar judgments. By spotting patterns and rulings in similar scenarios, it helps you anticipate how a judge might think and build a strategy that’s in line with current legal standards, making your arguments both relevant and persuasive.

Navigating the Procedural Labyrinth of a Section 417 Case

Knowing the black-and-white text of the law is one thing; navigating the maze of the court system is an entirely different beast. When you're dealing with a case under IPC Section 417, understanding the procedural roadmap is absolutely critical, whether you're the one making the complaint or the one defending against it.

The entire process usually kicks off when the person who feels cheated decides to set the criminal law in motion. This can happen in a couple of ways. Most commonly, they’ll lodge a First Information Report (FIR) with the police. Because Section 417 is a cognizable offence, the police can get started and even make an arrest without waiting for a court order. The other path is filing a private complaint directly with a Magistrate under Section 200 of the CrPC.

From Investigation to Charge Framing

Once an FIR is on the books, the police investigation begins. Think of this as the crucial fact-finding stage. Investigators will be on the ground, recording statements from anyone involved, digging up documentary proof—like incriminating emails or WhatsApp chats—and piecing together any circumstantial evidence that points to those essential ingredients of cheating we talked about: deception and that all-important dishonest intent right from the start.

After the investigation wraps up, the police file their final report, often called a chargesheet, with the court. The magistrate doesn't just rubber-stamp this. They carefully review the report to see if there's enough of a prima facie case to even proceed. If the evidence looks solid enough on its face, the court takes the pivotal step of framing charges, which formally puts the accused on trial for an offence under IPC Section 417.

Presenting Evidence and Arguing the Case

With charges framed, the trial officially gets underway. The prosecution goes first, putting its witnesses on the stand and presenting evidence to build its case. Their goal is to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Then, the ball is in the defence's court. This is their chance to cross-examine the prosecution's witnesses, poke holes in their story, and present their own evidence and arguments to show why their client is not guilty.

Insights From Draft Bot Pro This whole journey is packed with drafting—from that initial complaint to bail applications and the final written arguments. A legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro is like having a procedural expert on call. It can help generate a solid initial complaint, formulate persuasive bail arguments tailored to your case, and even create strategic memos that break down the evidentiary strengths and weaknesses. It keeps you organised and a step ahead.

Common Defences in a Cheating Case

For the accused, a robust defence is everything. In an IPC Section 417 case, the defence strategy usually revolves around a few key arguments:

No Dishonest Intent: This is the cornerstone. The defence will hammer home the point that there was no dishonest intention (mens rea) when the deal was made.

It’s a Civil Dispute, Not a Crime: This is a powerful argument. The defence will often contend that the issue is simply a breach of contract—a promise that couldn't be kept, not a criminal act. A business deal gone sour doesn't automatically equal cheating.

There Was No Deception: The defence might also argue that the complainant wasn't actually fooled and knew all the relevant facts from the get-go.

From the first FIR to the final arguments, the entire process demands a sharp eye for detail and a solid grasp of criminal procedure. If you want to dive deeper into the nuts and bolts of court processes, you might find our guide on Navigating India's Criminal Rules of Practice helpful.

Cheating Laws Get a Major Overhaul with BNS Section 318

The entire landscape of Indian criminal law is being redrawn. With the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) stepping in to replace the old Indian Penal Code, a lot is changing. For the offence of simple cheating, this means a shift from IPC Section 417 to the new BNS Section 318—and it's not just a change in number.

The most significant update? The punishment. Section 417 capped imprisonment at a mere one year. BNS Section 318 cranks that up significantly, tripling the maximum sentence to a much more serious three years.

Why the Harsher Penalty?

This isn't a random increase. It’s a deliberate move by lawmakers to give the law against cheating some real teeth. The reality is, the relatively light punishment under the old IPC often felt like a slap on the wrist, especially when dealing with modern, sophisticated forms of deception.

Legislators have clearly recognised that cheating, even when no property changes hands, can cause immense harm. Think about the damage done in digital scams or matrimonial fraud. This stricter approach will undoubtedly change the game. We'll likely see a shift in how plea bargains are negotiated, as defendants now face a much bigger downside. It also gives judges more room to hand down sentences that truly fit the crime.

This transition, which kicked in on 1st July 2024, is a big deal. It’s backed by some sobering numbers: between 2015 and 2023, around 89,000 cases were lodged under Section 417, but conviction rates hovered between just 32-38%. The 200% jump in the maximum penalty—from 12 to 36 months—is a direct response to that. You can dig deeper into the IPC section 417 statistics on Lawrato.

Staying on Top of the New Laws

For any legal professional, keeping up with these changes isn't just good practice; it's absolutely critical. Sticking to the old IPC provisions is a recipe for disaster—it can lead to bad advice, flawed charge sheets, and cases getting thrown out. This isn't just a minor update; it's a complete overhaul. Every single document you create, from a basic complaint to your in-depth research notes, needs to be built on the new BNS framework.

Insights From Draft Bot Pro When the law itself undergoes such a massive shift, you need tools that can keep pace. A legal AI platform like Draft Bot Pro is constantly updated to reflect the very latest legislative changes. This means when you’re working on a cheating case, the platform automatically aligns with the new BNS Section 318. You're not just drafting; you're drafting with accuracy, shielded from the embarrassing and professionally damaging mistake of citing a repealed law. It ensures your advice and your documents are built on the solid ground of current legal standards.

Getting to Grips with IPC Section 417: Your Questions Answered

Let's tackle some of the most common questions that pop up for legal professionals and students when dealing with the nuances of IPC Section 417. These quick-fire answers should help clear up any confusion.

Can a Simple Breach of Contract Land Someone in Trouble Under IPC 417?

Not really, no. A straightforward failure to keep a promise made in a contract doesn't automatically mean it's a criminal case of cheating.

The prosecution has a high bar to clear: they must prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that a dishonest intention (mens rea) was there from the very beginning. The Supreme Court has hammered this point home time and again. If someone simply can't fulfil their end of the deal later on, that’s a civil matter, not a criminal one—unless you can show they planned to defraud from the get-go.

Key Insights This distinction is the bedrock of many such cases. Without proof of dishonest intent at the inception of the agreement, the case will likely get thrown out. It reinforces that critical line between civil and criminal liability. A simple payment default or a delay in delivery, on its own, just won't cut it for a charge under IPC Section 417.

What’s the New Punishment for Cheating Under BNS Section 318?

The new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) is taking a much tougher stance. Its equivalent provision, Section 318, which is set to replace IPC Section 417, dramatically increases the penalty.

The maximum jail time is jumping to three years, or a fine, or both. That’s a whopping 200% increase from the one-year maximum under the old IPC. It's a clear signal that the law is cracking down on these kinds of offences.

How Do You Actually Prove Dishonest Intention in Court?

Proving what was in someone's mind is always tricky. You can't read thoughts, so courts have to rely on circumstantial evidence to piece together the accused's state of mind at the time.

Here’s what they typically look for:

A History of Deception: Has the accused done this sort of thing before with other people? A pattern speaks volumes.

Outright Lies: Can you show the accused made provably false statements to lure the victim into the deal?

Hiding Key Facts: Did they deliberately conceal crucial information that, if known, would have made the victim walk away?

Zero Effort to Follow Through: Did the accused make any real attempt to fulfil their promise, or did they just take the money and run?

A classic example is someone promising marriage while they are already married. That's a pretty open-and-shut case of having dishonest intent from the very start.

How Draft Bot Pro Can Help This is where legal AI can be a game-changer. A tool like Draft Bot Pro can sift through mountains of case files and communications, flagging suspicious patterns or phrases that point to a pre-existing dishonest intent. It helps you build a much more solid, evidence-backed argument.

Is an Offence Under Section 417 Bailable?

Yes, it is. An offence under IPC Section 417 is bailable, meaning the accused has the right to be released on bail.

It's also cognizable, which gives the police the power to make an arrest without needing a warrant. However, it's important to remember that the offence is non-compoundable. This means the complainant can't just drop the case by reaching a settlement with the accused; it requires the court's permission to be withdrawn.

Stop losing hours to manual legal work. With Draft Bot Pro, you can generate precise legal documents and run source-backed research in minutes. Join over 46,000 legal professionals across India who trust our AI to sharpen their practice. Start your free trial today.