Tweddle v Atkinson: tweddle v atkinson explained

- Rare Labs

- 16 hours ago

- 19 min read

Picture this: a wedding is on the horizon, promises of money are made to support the new couple, but when the time comes to collect, the groom is left high and dry with no legal way to claim his due. This isn't just a dramatic story; it's the real-life scenario at the heart of Tweddle v Atkinson, a foundational 19th-century English case that every legal professional in India should know inside and out.

Unpacking The Landmark Tweddle v Atkinson Case

The story behind Tweddle v Atkinson is surprisingly simple, yet it perfectly demonstrates a massive legal principle. It all started with an agreement between two fathers, John Tweddle and William Guy, whose children were getting married.

To give the newlyweds a good financial start, the fathers made a written pact. Each promised to pay a sum of money to the groom, William Tweddle. A straightforward plan, right? Well, as we know, law and life are rarely that simple.

A Promise Made But Not Kept

The trouble began after the wedding. The bride's father, William Guy, passed away before he paid up. So, the groom, William Tweddle, did what he thought was logical: he sued the executor of his late father-in-law's estate, Mr. Atkinson, to get the money he was promised.

It seems only fair. The money was meant for him, after all. But the court had a very different take, and its decision would shape contract law for generations. The judgment, handed down on 7 June 1861, was clear: even though the contract was explicitly for his benefit, William Tweddle had no legal right to sue. Why? Because he was a "stranger to the consideration."

This ruling hammered home the doctrine of privity, establishing that consideration must come from the person who is trying to enforce the contract.

To make sense of who's who, let's break down the key players involved.

Key Parties and Their Roles in Tweddle v Atkinson

Party | Role | Key Action/Promise |

|---|---|---|

William Tweddle | The Groom / Plaintiff | Sued the estate to receive the promised money. |

John Tweddle | Groom's Father | Promised to pay £100 to his son. |

William Guy | Bride's Father | Promised to pay £200 to the groom but passed away before doing so. |

Mr. Atkinson | Executor of Guy's Estate / Defendant | Was sued by the groom for the unpaid amount. |

This table clearly shows that while William Tweddle was the intended beneficiary, he wasn't one of the two parties who actually made the promises and provided the consideration. That's the crux of the issue.

Insights: The court's decision in Tweddle v Atkinson set a strict precedent. If you're not a direct party to a contract and didn't provide any consideration, you can't sue to enforce it, even if you were supposed to benefit from it.

Why This Case Still Matters Today

For any lawyer in India, this case is essential reading. It lays the groundwork for core contract law principles that the Indian legal system has both adopted and adapted in its own unique way. While the doctrines of privity and consideration are fundamental, their application in India has evolved, creating nuances you need to understand.

This is where knowing the history helps build stronger arguments today.

Historical Context: Understanding where these legal principles come from gives you a solid foundation for your arguments.

Comparative Analysis: Knowing the English precedent helps you see exactly how and why Indian law has carved its own path.

Efficient Research: Being able to quickly pull up and analyse cases like this is a game-changer for building a winning legal strategy.

This is exactly why modern legal tools are so valuable. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can instantly give lawyers and students in India case summaries, find relevant precedents, and pinpoint the differences between English common law and the Indian Contract Act, 1872. It lets you ground your arguments in deep historical context while applying current Indian law with speed and precision. For a better grasp on the fundamentals, you can check out our guide on what legal research methodology is.

Decoding the Core Legal Principles of the Case

To really get why William Tweddle walked away with nothing, we have to dig into the two legal pillars the court's decision rested on. These principles, privity of contract and consideration, created a legal fortress that the groom just couldn't breach, even though the agreement was made entirely for his benefit.

Think of a contract as an exclusive club. Only the people who sign up and pay the membership fee—the actual parties to the contract—get to enjoy the perks and are bound by the rules. This idea of exclusivity is the very heart of the doctrine of privity.

In Tweddle v Atkinson, the club members were the two fathers, John Tweddle and William Guy. They were the ones who made the promises and shook hands on the deal. William Tweddle, the groom, was the person they all wanted to help, but he wasn't a member. He was an outsider looking in, and in the eyes of the law, outsiders have no rights.

The Doctrine of Privity of Contract

The court's reasoning was sharp and unforgiving. The doctrine of privity of contract means that a person cannot sue on a contract if they are not a direct party to it. It makes no difference if the entire point of the contract was to benefit them; if your name isn't on the dotted line as a party, you have no legal standing to enforce it.

For William Tweddle, this was a non-starter. His claim was dead on arrival. The agreement was between his father and his father-in-law. Since he was a ‘stranger’ to this contract, the court ruled he had no right to sue Mr. Atkinson's estate.

This principle is there for a reason—it prevents a potential flood of lawsuits from third parties who might be tangentially affected by an agreement. But as this case so clearly shows, it can also lead to outcomes that feel deeply unfair, especially when the third party was the one and only intended beneficiary.

Insights from the Bench: Wightman, J., one of the judges on the case, put it bluntly: "It is now established that no stranger to the consideration can take advantage of a contract, although made for his benefit." This single sentence perfectly captures the rigid logic that sealed William Tweddle's fate.

Grasping this fundamental rule is non-negotiable for legal professionals. When you’re looking at any agreement, the first question should always be: who are the actual parties? This is where legal AI can give you a head start. By uploading an agreement to Draft Bot Pro, lawyers in India can instantly identify the contracting parties and flag potential privity issues, making sure their strategy is built on solid ground.

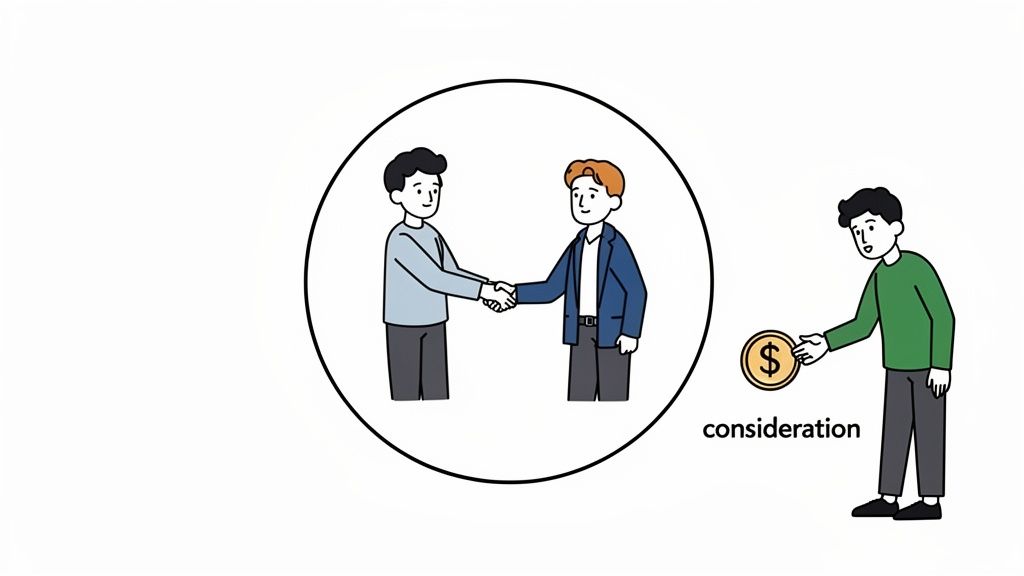

The Concept of Consideration

The second pillar propping up the court's decision was the rule of consideration. If privity is about who is in the club, consideration is the price of admission. It’s the value—whether it's money, goods, a service, or a promise—that each party brings to the table to make the contract legally binding.

You can think of it as the 'price of the promise'. For a promise to be legally enforceable, the person trying to enforce it must have 'paid' for it by providing some consideration of their own.

The court in Tweddle v Atkinson looked at what, exactly, William Tweddle had personally contributed to this deal. The answer was simple: nothing. The consideration for William Guy's promise to pay £200 was John Tweddle's counter-promise to pay £100. The groom himself hadn't promised or given a single thing in return.

This was the fatal flaw in his case. Since he had provided no consideration, he hadn't 'bought' the right to enforce the promise made for his benefit.

Here’s how the two principles worked together to shut the door on the groom's claim:

Privity Rule: He wasn't a party to the contract.

Consideration Rule: He didn't provide any consideration for the promise.

These two concepts are two sides of the same coin. The court essentially said that only a person who has provided consideration can be seen as a party to the contract for the purposes of a lawsuit. This powerful one-two punch set a firm precedent that has shaped contract law across the common law world for over 150 years.

How Indian Law Sees Tweddle v Atkinson Differently

While Tweddle v Atkinson is a landmark case in English common law, its principles didn't just get copy-pasted into the Indian legal system. Think of it more as a story of adaptation, not blind adoption. Indian courts certainly acknowledge the case, but they operate within a completely different universe: the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

This single piece of legislation fundamentally reshapes the rigid English rules of privity and consideration, creating a much more flexible—and often fairer—outcome for people who stand to benefit from a contract, even if they aren't technically a party to it.

The real game-changer is Section 2(d) of the Indian Contract Act. This clause defines 'consideration' in a way that directly cuts through the logic that blocked William Tweddle from his inheritance. It states that consideration can come from the promisee or from "any other person."

This might seem like a small tweak in wording, but the legal earthquake it creates is massive. It completely severs the strict link between being a party to the contract and providing the consideration, which was the exact wall William Tweddle ran into.

The Power of Section 2(d) of the Indian Contract Act

Back in England, the rule was brutally simple: if you didn't provide some form of 'payment' for the promise (the consideration), you had no right to enforce it. The Indian Contract Act, however, takes a much more practical and broader view.

Insights on Indian Law: "When, at the desire of the promisor, the promisee or any other person has done or abstained from doing, or does or abstains from doing, or promises to do or to abstain from doing, something, such act or abstinence or promise is called a consideration for the promise." - Section 2(d), Indian Contract Act, 1872.

What this means in plain English is that someone else can provide the consideration on your behalf. If the two fathers in Tweddle v Atkinson had struck their deal in India, the whole case would have likely gone the other way. The groom's father providing his share of the money would have been enough for the groom to sue, simply because the consideration came from "any other person."

A Landmark Indian Case: Chinnaya v Ramayya

The real-world impact of this legal shift is perfectly captured in the classic Indian case of Chinnaya v Ramayya (1882). The setup feels incredibly familiar, involving a family promise and a third person meant to benefit.

Here's what happened: an elderly woman gifted some property to her daughter, Ramayya. But there was a catch. The gift came with a clear instruction that the daughter had to pay a yearly sum (an annuity) to her own maternal aunt, Chinnaya. The daughter agreed to this, but after receiving the property, she stopped making the payments.

When the aunt, Chinnaya, took her niece to court, the niece's defence was straight out of the Tweddle v Atkinson playbook. She argued that her aunt hadn't provided any consideration for the promise, making her a "stranger to the consideration" and therefore unable to sue.

The court wasn't having it. It ruled that the property gifted by the mother was more than enough consideration for the daughter's promise to pay the aunt. Because Section 2(d) allows consideration to move from "any other person," the mother's gift was legally sufficient to let the aunt enforce the promise.

The Chinnaya v Ramayya case is a fantastic illustration of how Indian law, while aware of English precedents, carves its own path. For a deeper dive into how the Indian legal framework reinterprets these principles, check out this detailed legal analysis.

To make this distinction crystal clear, let's break it down.

Tweddle v Atkinson vs Indian Contract Act 1872

Here’s a side-by-side comparison that gets right to the heart of the matter, showing how English common law and the Indian statute differ on these core contractual principles.

Legal Principle | Stance in Tweddle v Atkinson (English Law) | Stance in Indian Contract Act, 1872 |

|---|---|---|

Privity of Contract | Very strict. Only a person who is a party to the contract can sue on it. | Relaxed. Exceptions allow a third-party beneficiary to sue in certain circumstances (e.g., trust, family arrangements). |

Privity of Consideration | Extremely strict. Consideration must move from the promisee only. A third party cannot provide it. | Completely different. Section 2(d) explicitly allows consideration to move from the promisee or "any other person." |

Third-Party Beneficiary Rights | A third-party beneficiary has no right to enforce the contract, even if it was made for their direct benefit. | A third-party beneficiary can enforce the contract, provided there is valid consideration, even if they didn't provide it themselves. |

This table shows that while the concept of being a 'party to a contract' is still important in India, the rigid barrier of 'consideration' that tripped up William Tweddle has been effectively dismantled by statute.

How Draft Bot Pro Helps You Master These Nuances

For any lawyer in India, simply knowing the English precedent isn't enough—you have to know how Indian law modifies it. This is precisely where a specialised legal AI assistant becomes your most powerful paralegal.

Draft Bot Pro isn't a generic AI; it’s built from the ground up for the Indian legal system. Imagine you have a case involving a third-party beneficiary. You can just upload the facts and ask the AI to:

Pinpoint Key Statutes: It will instantly flag Section 2(d) of the Indian Contract Act as the make-or-break provision for your case.

Find Indian Precedents: Forget hours of research. It will pull up foundational cases like Chinnaya v Ramayya to back up your argument that consideration from a third party is perfectly valid.

Sharpen Your Arguments: It can help you draft sections of your pleadings or legal notices that skillfully apply Indian law, clearly distinguishing your client's situation from the outdated English rule in Tweddle.

By having a tool like this in your corner, you ensure every argument you make is firmly rooted in the specifics of Indian law, not just a historical case from another country.

Drafting Modern Arguments with AI-Powered Insights

Knowing the history of Tweddle v Atkinson is one thing. But turning that textbook knowledge into a winning strategy for a client in India today? That’s a whole different ball game. This is where legal theory has to get its hands dirty and become powerful, practical advocacy.

Let's jump from the 19th-century English countryside straight into the middle of India's buzzing startup scene. This will show you exactly how old precedents and new tools come together to build a case that’s tough to beat.

A Modern Hypothetical Scenario

Picture this: two co-founders of a tech startup sign a formal, written agreement with each other. In that contract, they make a clear promise: they will grant a 5% equity stake to their lead developer, Priya, as soon as the company secures its first round of funding.

Now, Priya isn't a signatory on this co-founder agreement. But her critical role and the promised equity are spelled out in black and white. She grinds away, often for a lower salary, banking on this promise. The funding comes through, but the founders suddenly get amnesia and refuse to transfer the equity.

If we were bound by the rigid ruling of Tweddle v Atkinson, Priya would be out of luck. She’s a "stranger to the contract" and didn't directly provide consideration for the promise the founders made to each other. But here in India, her lawyer has a much stronger hand to play, all thanks to the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

Building the Winning Argument Step-by-Step

A sharp lawyer wouldn't even try to fight the old English precedent head-on. Instead, they’d sidestep it and anchor their argument firmly in Indian law. The entire strategy would be about showing how Priya’s situation is worlds away from the one that failed in court over 150 years ago.

Here's how that argument would be structured:

Acknowledge and Sidestep Tweddle v Atkinson: You start by showing you know your history. Acknowledge the classic privity rule. Then, immediately pivot to explain precisely why it’s irrelevant here, thanks to the overriding authority of Indian statutes.

Make Section 2(d) of the Indian Contract Act Your Hero: This is the heart of the entire case. You hammer home the point that in India, consideration can move from "any other person." The mutual promises between the co-founders are more than enough valid consideration for the promise made to benefit Priya.

Bring in the Indian Heavyweights: Back it up with landmark cases like Chinnaya v Ramayya. This shows that Indian courts have a long history of protecting third-party beneficiaries where consideration exists, even if it didn't flow directly from them.

Frame it as a Trust or Special Arrangement: You can also argue that the founders' agreement essentially created a trust or a special family-like arrangement for Priya's benefit. Indian courts are often more flexible in enforcing promises in these contexts to prevent a clear injustice.

This approach completely reframes the narrative. Priya goes from being a helpless "stranger" to a legally recognised beneficiary with rights she can actually enforce.

Insights: The key isn't to argue that Tweddle v Atkinson was wrong. The key is to show that Indian law has carved out a more equitable and practical path. Your goal is to prove that while the English case is a historical footnote, it's not legally binding when specific Indian laws say otherwise.

The Role of Legal AI in Crafting Your Case

Manually pulling together all the research, drafting the notice, and cross-referencing cases is a grind. It’s time-consuming and tedious. This is exactly where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro becomes a modern lawyer's secret weapon. It provides a clear, efficient way to turn the facts of a case into a powerful legal notice or pleading.

Here’s how you’d use a tool like Draft Bot Pro for Priya’s case:

Upload Case Facts: Just input the details of the co-founder agreement and what happened to Priya.

Generate a Preliminary Notice: Ask the AI to draft a legal notice to the co-founders. It will instantly cite Section 2(d) and build the core argument, saving you hours of initial drafting.

Perform Expert Research: Tell the AI to find supporting Indian case law. It can quickly pull up precedents that distinguish your case from the strict ruling in Tweddle v Atkinson, making your position rock-solid.

Anticipate Counter-Arguments: You can even ask the AI to play devil's advocate, identifying potential arguments the other side might use and helping you prep your rebuttals before they even think of them.

By letting AI handle the heavy lifting of research and first drafts, you get to focus on the high-level strategy that actually wins cases. This blend of historical knowledge, statutory expertise, and AI-powered efficiency is what defines top-tier legal work today. To get a better sense of how these tools are changing the game, learn more about the role of an AI legal research assistant. As AI becomes more crucial for building legal arguments, it's also smart to explore the wider tech landscape, including the best AI search tracker tools, to understand all the technologies available.

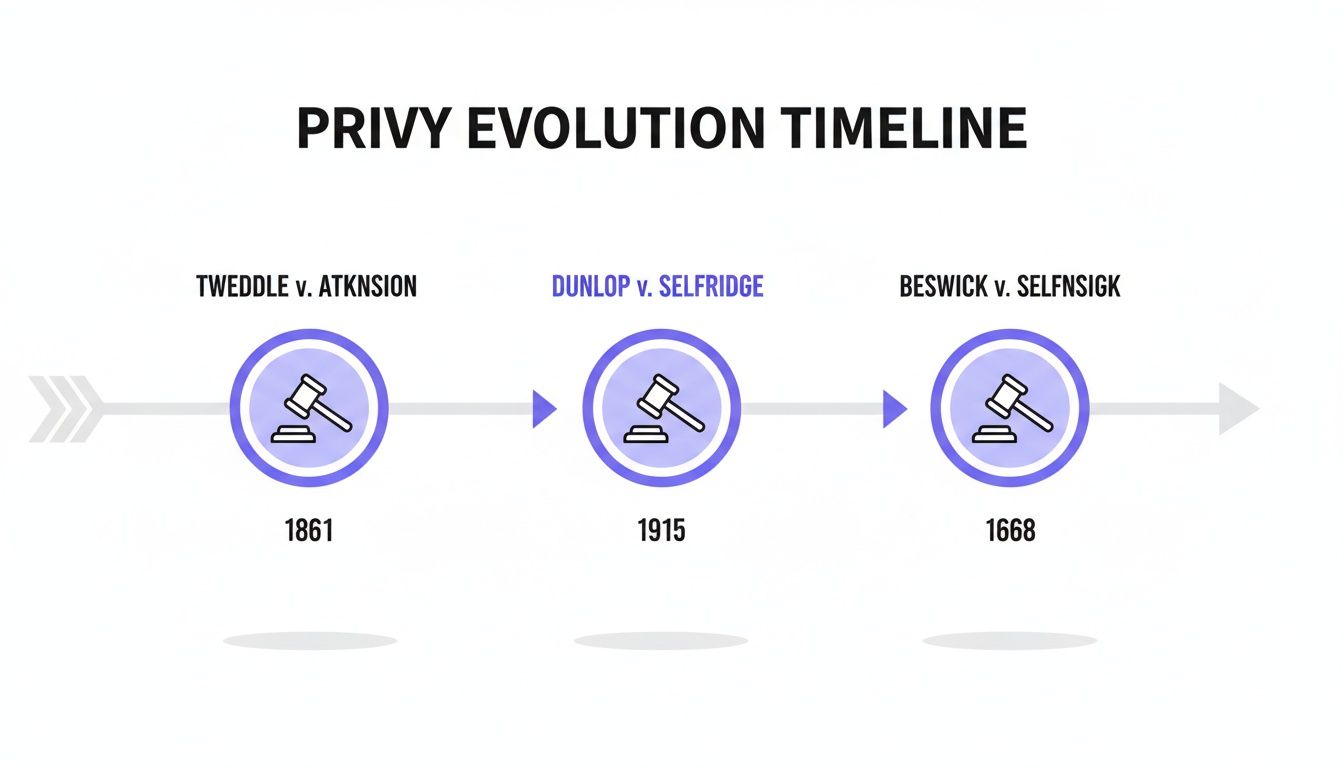

The Evolution of Privity and Its Modern Exceptions

The rigid rule laid down in Tweddle v Atkinson was a huge moment for contract law, but it was never going to be the final word. While the doctrine of privity created a clean, logical line, it also paved the way for outcomes that just felt plain wrong. Over time, courts began to see that applying the rule so strictly could completely undermine the original point of an agreement, leading to a slow but sure evolution of the law.

This shift didn't happen overnight. For a while, the precedent from Tweddle v Atkinson was actually strengthened. The landmark case of Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v Selfridge & Co Ltd (1915) doubled down on the idea, confirming that only someone who is a party to a contract and has provided consideration can sue on it. For decades, this cemented the privity doctrine as a cornerstone of English law.

But the cracks started to appear. The case of Beswick v Beswick (1967) really shone a light on how unfair the rule could be. In that case, a man sold his business to his nephew. The deal was that the nephew would pay a weekly sum to the man's wife after he died. When the man passed away, the nephew simply stopped paying. As a third party, the widow couldn't sue in her own right. It was a classic Tweddle v Atkinson problem, and it screamed for a more sensible approach.

Key Exceptions to the Privity Rule

To stop these kinds of unfair results, both courts and legislatures started to carve out important exceptions to the strict privity rule. You can think of these as "safety valves," making sure that the people who were meant to benefit from a contract aren't left high and dry. These principles are now recognised in both English and Indian law, opening up vital paths for third-party claims.

Some of the most critical exceptions include:

Trust or Charge: If a contract effectively creates a trust for a third party, that person (the beneficiary) can enforce it. A classic example is when property is transferred to someone with a clear instruction to pay a third person from the property's income. That's a trust.

Agency: When an agent makes a contract on behalf of their principal, the principal can sue on it. This is true even if the principal wasn't in the room for the negotiations. The agent is just a channel for the principal.

Assignment of a Contract: The rights and benefits of a contract can often be legally transferred, or "assigned," to a third party. Once that assignment is complete, the third party steps into the shoes of the original party and can enforce the contract.

Contracts for the Benefit of a Third Party: This is a wider category, and it's particularly important in India. In situations like family arrangements or marriage settlements, courts are often willing to let a third-party beneficiary sue to make sure the family's intentions are honoured.

Modern Examples of the Exceptions in Action

These exceptions aren't just dusty legal theories; they pop up in everyday situations.

Insights: The evolution of privity shows a clear shift in legal thinking—away from rigid rules and towards achieving real justice. The courts realised that the main job of contract law is to make the parties' intentions a reality, even if that means looking beyond the list of names on the signature page.

Think about a standard life insurance policy. You take out a policy and name your spouse or child as the beneficiary. You're creating a contract with the insurance company for the benefit of a third person. If we were still stuck with the strict Tweddle v Atkinson rule, your family member would have no power to sue the insurance company if it refused to pay. Thanks to statutory exceptions and the principles of trust, this is now completely enforceable.

How Draft Bot Pro Simplifies Navigating Exceptions

For lawyers in India, figuring out the right exception to the privity rule is half the battle. The line between a simple third-party benefit and an enforceable trust can be razor-thin, often coming down to the specific words used in the agreement and the context of the deal. This is where modern legal tools give you a real edge.

With Draft Bot Pro, you can upload a contract and get an instant analysis of potential third-party rights. Our AI can pinpoint clauses that might create a trust or charge and pull up relevant Indian case law where similar exceptions were argued successfully. Instead of spending hours hunting for precedents, you get solid insights in minutes. This allows you to build a stronger, more legally sound argument from the get-go. You can learn more about how to apply these concepts by reading our guide on the subsidiary rules of interpretation. It’s all about making sure you use every legal tool available to protect your client.

Key Takeaways and Final Insights for Lawyers

So, what's the big takeaway from Tweddle v Atkinson for legal professionals in India today? It really boils down to this: you have to respect legal history, but you must master your local law. This case is absolutely foundational for understanding why the doctrine of privity exists, but your success as a lawyer hinges on knowing how to apply the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

The timeline below really puts the evolution of the common law on privity into perspective, with Tweddle as the starting block.

You can see a clear journey here, moving away from rigid, sometimes unfair rules towards achieving more just outcomes for people who were clearly meant to benefit from a contract.

Practical Tips and Final Insights

At the end of the day, your job is to connect that legal history with sharp, modern advocacy. For any lawyer getting to grips with the subtleties of landmark cases like Tweddle, a solid modern guide to contracts for lawyers can be a huge help. A deep appreciation for common law principles, paired with a rock-solid command of Indian statutes, is what separates a good lawyer from a great one.

Insights: Let's be honest, using AI tools like Draft Bot Pro isn't just a neat trick anymore; it’s a strategic necessity. It helps you quickly connect the dots between historical precedents and current Indian law, giving you a real leg up in your research and drafting work.

Here’s a simple checklist to keep you on the right track:

Your starting point is always the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and specifically Section 2(d). No exceptions.

Treat English cases like Tweddle v Atkinson as a source of context and background, not as a binding rule.

Become an expert on the Indian exceptions to privity—things like trust, agency, and family arrangements are your bread and butter.

Frequently Asked Questions

When you're digging into contract law, some questions pop up again and again, especially around landmark cases like Tweddle v Atkinson. Let's clear up some of the common sticking points to make sure these core legal ideas are crystal clear.

What Is the Main Rule from Tweddle v Atkinson?

At its heart, Tweddle v Atkinson cemented the doctrine of privity of contract into English law. Think of it this way: a contract is like a private club. The rule says only the members of that club—the people who actually made the agreement—can sue to enforce it or be held responsible under it.

Even if you're the one who was supposed to get all the benefits from the contract, if you're not an official "member," you have no legal power to demand what was promised. You're just a stranger looking in from the outside.

How Does Consideration Relate to This Case?

Consideration is what each party gives up to make a deal stick; it's the legal "price" of a promise. The court in Tweddle v Atkinson was incredibly strict about this. They ruled that consideration has to move from the person trying to enforce the promise (the promisee).

In this case, the groom, William Tweddle, didn't offer anything in return for the money. The promises were a back-and-forth between the two fathers. Because he hadn't put any "skin in the game" himself, he had no right to sue. This double whammy—being a stranger to the deal and providing no consideration—was the nail in the coffin for his claim.

Insights: The case really tightened the link between giving consideration and earning the right to sue. You can't just be a bystander waiting for a benefit; under this traditional English common law view, you have to be an active part of the bargain to have enforceable rights.

Is the Tweddle v Atkinson Rule Still Followed in India?

Here's where things get interesting. While Indian law does recognise the doctrine of privity, its bite is much less severe thanks to the Indian Contract Act, 1872. The game-changer is Section 2(d) of the Act.

This section states that consideration can come from the promisee or "any other person." This one little phrase completely changes the dynamic. It breaks the rigid link that Tweddle v Atkinson created. As a result, someone in India who is meant to benefit from a contract has a much better shot at enforcing it, a principle we see in action in cases like Chinnaya v Ramayya.

How Can AI Help with Privity of Contract Issues?

Figuring out if your client can sue as a third party isn't always straightforward. It means diving deep into the contract's wording and lining it up against current case law. This is exactly where a specialised legal AI becomes a massive help.

An AI tool like Draft Bot Pro is built for these very challenges faced by Indian legal professionals. Just upload your client's agreement, and the AI gets to work:

It immediately flags any clauses that name third-party beneficiaries.

It analyses how consideration flows, but through the lens of Indian law, not outdated English rules.

It pulls up relevant Indian case law that could either back up or challenge a third party's right to sue, cutting through the noise of old precedents like Tweddle v Atkinson.

This means you can get a quick, accurate read on the strength of a potential case and start building your strategy on solid, India-specific legal ground. It saves you hours of manual research and lets you focus on the argument itself.

Ready to build stronger legal arguments with the power of AI? Draft Bot Pro is the most affordable and verifiable legal AI built by lawyers, for lawyers. Trusted by over 46,379 legal professionals in India, our platform helps you conduct accurate legal research and draft precise documents in minutes. Start your free trial today and discover a smarter way to practice law.