The Wagon Mound Case A Guide to Reasonable Foreseeability

- Rare Labs

- 9 hours ago

- 17 min read

The Wagon Mound case didn't just tweak a rule; it completely reshaped how we think about responsibility in negligence. It drew a clear line in the sand, establishing that you're only on the hook for damages that are reasonably foreseeable. This was a massive departure from the old way of thinking, where you could be held liable for all direct consequences of your actions, no matter how wild or unpredictable.

Why The Wagon Mound Case Still Matters in Tort Law

The story kicks off with a simple, almost mundane act of carelessness in Sydney Harbour. A ship, the Wagon Mound, negligently spilled a huge amount of furnace oil into the water. The thick, black sludge drifted over to a nearby wharf where welders were hard at work.

What unfolded next triggered a legal earthquake. Sparks from the welding ignited some floating debris caught in the oil slick. This set off a colossal fire that torched the wharf and other ships. The core legal question was a big one: should the ship's owners have to pay for the fire damage—a result so bizarre that experts at the time insisted it was impossible to ignite furnace oil floating on water?

The Old Rule: A Chain of Direct Consequences

Before Wagon Mound came along, negligence law ran on a principle from an older case, Re Polemis. The rule was brutally simple: if you were negligent, you were liable for all direct consequences of that act. It didn't matter if the outcome was freakish or unforeseeable. If you started the domino chain, you paid for where it ended.

This created a real problem. A small slip-up could lead to a catastrophic, completely unpredictable disaster, and the defendant would have to foot the entire bill. The system was crying out for a fairer, more sensible approach.

The New Rule: Introducing Reasonable Foreseeability

The Wagon Mound case threw the Re Polemis rule out the window. The Privy Council brought in a more refined test: reasonable foreseeability. The idea is that a defendant is only liable for damage of a kind that a reasonable person could have actually foreseen as a possible result of their carelessness.

Insights: This wasn't just a dry legal change; it was a fundamental shift towards common sense and fairness. It anchors liability to predictable risks, making sure people and businesses aren't held responsible for freak accidents that nobody could have realistically seen coming.

To get a clearer picture of how dramatically the law changed, let's break it down.

At a Glance: How Wagon Mound Reshaped Negligence

Here’s a quick comparison of the legal landscape before and after this landmark decision.

Legal Standard | Before Wagon Mound (Re Polemis Rule) | After Wagon Mound (Foreseeability Rule) |

|---|---|---|

Basis of Liability | Direct consequence of the negligent act. | Reasonable foreseeability of the kind of damage. |

Scope of Liability | Potentially limitless. If the act was a direct cause, you were liable for everything that followed. | Limited to what a reasonable person would have foreseen as a potential risk. |

Fairness | Could lead to harsh and unfair outcomes, holding people liable for bizarre accidents. | Considered a fairer test, as it links liability to what is reasonably predictable. |

The introduction of the foreseeability test brought a much-needed dose of reality and justice into the law of negligence, a principle that continues to be the bedrock of tort law today.

This single event actually led to two landmark rulings, known as Wagon Mound (No. 1) and Wagon Mound (No. 2). Each case had different parties and focused on slightly different legal arguments, which together helped flesh out what "foreseeable" really means. While these principles come from a Commonwealth court, you can explore how Indian courts have grappled with other major legal ideas in our guide to landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India.

For legal professionals dealing with tricky tort claims, a tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. Its AI Legal Research feature can instantly pull up precedents applying the foreseeability test, helping you build a stronger case based on the specific facts. It’s perfect for tracing how legal principles have evolved, ensuring your arguments are sharp and current.

The First Ruling: Wagon Mound (No. 1)

The first chapter in this legal saga, officially known as Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Morts Dock & Engineering Co Ltd, starts with a single, careless act that had explosive results. The crew working on the Wagon Mound ship negligently let a large amount of thick furnace oil spill right into Sydney Harbour.

This wasn't just some minor spill. The oil slick drifted across the water, eventually collecting around a wharf owned by Morts Dock. At that very moment, welders were busy with repairs on the wharf, sending a shower of sparks down towards the water.

At first, nobody panicked. The common understanding was that this type of furnace oil wouldn't catch fire when floating on water, so the welding continued. But then the unthinkable happened. Sparks landed on some floating cotton debris soaked in the oil, which acted like a wick, igniting the entire oil slick. The resulting inferno caused catastrophic damage to the wharf and nearby ships, setting the stage for a legal fight that would challenge the very rules of negligence.

The Court's Decisive Shift Away From Precedent

The whole case boiled down to one question: were the ship's owners liable for the fire damage? The claimants, Morts Dock, built their case on the long-standing Re Polemis rule. This precedent was simple—if you were negligent, you were liable for all direct consequences of your actions, whether you could have predicted them or not.

The ship owners, Overseas Tankship, pushed back hard. They argued that liability should be capped at what was reasonably foreseeable. Their key evidence came from experts who testified that, based on scientific knowledge at the time, getting furnace oil to ignite on water was practically impossible. A fire, they contended, was simply not a foreseeable outcome of spilling oil.

This left the Privy Council at a crossroads. Should they stick with the established, but often criticized, Re Polemis rule, or should they forge a new path based on foreseeability?

Insights: The court’s decision turned on a subtle but crucial point: the type of damage. The damage from the oil fouling up the wharf (the pollution) was obviously foreseeable. But the court saw the fire damage as a completely different and unforeseeable kind of harm, especially given the evidence presented.

In the end, the Privy Council sided with the defendants. They threw out the Re Polemis rule, calling it unjust. They established a new test: liability for damage only exists if the kind of damage suffered was reasonably foreseeable. Since the fire was not considered foreseeable, the ship owners were not held liable for it.

This judgment, delivered on 18 January 1961, wasn't just about one case. It completely reshaped tort law. Wagon Mound (No. 1) established reasonable foreseeability as the definitive test for remoteness of damage, a principle that profoundly influenced Indian jurisprudence, which had previously followed the Re Polemis standard.

Why This Shift Was Necessary

The logic behind the court's decision was to create a fairer system. They wanted to prevent defendants from being held responsible for an endless chain of bizarre and unpredictable consequences. The goal was to tie liability directly to what a reasonable person would anticipate and take steps to prevent.

Here are the core principles that came out of Wagon Mound (No. 1):

Rejection of Direct Consequence: The court officially overruled Re Polemis. The idea that a defendant is liable for every single direct result of their negligence was gone.

Establishment of Foreseeability: The "reasonable foreseeability" test became the new gold standard for determining if damage is too remote.

Focus on the Kind of Damage: For liability to stick, the specific type of harm that actually happened must have been a foreseeable result of the negligent act.

This landmark ruling created a more predictable and just framework for negligence claims. But the story wasn't quite over. A second case, stemming from the very same incident but involving different claimants and crucial new evidence, was about to put this brand-new principle to the test.

Round Two: The Wagon Mound (No. 2)

The story of the Sydney Harbour fire didn't just wrap up neatly after the first case. The same destructive event sparked a second lawsuit, Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Miller Steamship Co Pty Ltd, but this time with a fresh set of claimants and a much smarter legal strategy. This second go, famously known as Wagon Mound (No. 2), didn't throw out the first ruling. Instead, it added a critical layer of nuance to the whole idea of foreseeability.

The new claimants were the owners of two ships, the Corrimal and the Audrey D, that got torched in the fire. Unlike the wharf owners in the first case, this legal team came prepared for a different kind of fight. They built their case on two foundations: public nuisance and negligence. This was a savvy move that opened up new ways to bring in evidence.

A Fresh Look at Risk and Foreseeability

The game-changer in Wagon Mound (No. 2) was the new evidence brought to the table. The claimants' lawyers proved that while the risk of furnace oil catching fire on water was incredibly small, it wasn't zero. It wasn't some scientific impossibility.

They showed that any reasonable ship's engineer would have known about this tiny, but very real, possibility. The argument completely shifted. It was no longer about whether a fire was probable, but whether it was a 'real risk'—the kind of risk that a prudent person wouldn't just shrug off, no matter how slim the odds.

This new evidence painted an entirely different picture for the court. The fire was no longer a freak accident that nobody could have predicted. It was a remote possibility that a professional should have had in the back of their mind.

Insights: This case pivoted on a crucial refinement of foreseeability. It drove home the point that liability isn't just about what's likely to happen. You can also be held responsible for failing to prevent a small but known risk, especially when the negligent act—spilling oil all over a harbour—had absolutely no good reason or social benefit behind it.

The Court's Sharper Judgment

This time, the Privy Council saw things differently and held the ship owners liable for the fire damage. Lord Reid delivered a judgment that laid out a now-famous principle for figuring out foreseeability and the duty of care.

His logic was simple but powerful. A reasonable person who knows about even a small risk has to take steps to prevent it, especially if stopping it isn't difficult, expensive, or inconvenient. Since there was no good reason to spill the oil and stopping it was easy, failing to do so was a clear breach of duty. The risk of fire, even though small, was therefore 'foreseeable' in the eyes of the law.

Wagon Mound (No. 2) didn't get rid of the rule from No. 1. It just made it clearer with these key takeaways:

A "Real Risk" is Foreseeable: A risk doesn't have to be likely to be foreseeable. As long as it's a real, substantial risk that a reasonable person wouldn't dismiss as far-fetched, it passes the test.

Balancing Risk vs. Action: The court has to weigh the size of the risk against how hard or costly it would be to get rid of it.

No Excuse for Pointless Negligence: When a careless act has no redeeming value whatsoever, the duty to prevent even slight foreseeable risks becomes much stronger.

This ruling gave us a much more complete understanding of the foreseeability principle. It showed that the test isn't some rigid formula, but a flexible assessment of what a sensible, careful person would actually do in the circumstances.

For legal professionals dealing with complex negligence claims, telling the difference between these interpretations of foreseeability is everything. This is where a tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a massive help. Its AI Legal Research function lets you quickly find and compare case law that applies the nuanced principles from Wagon Mound (No. 2). You can ask it to pull up precedents involving "low probability, high consequence" risks, helping you build arguments that fit the unique facts of your case and show exactly why a particular risk, no matter how small, should have been taken seriously.

Comparing the Two Landmark Decisions

It’s one of the great head-scratchers in tort law: the same oil spill in Sydney Harbour led to two famous Wagon Mound cases with totally different outcomes. How is that possible?

The answer isn't just a legal curiosity; it’s a masterclass in legal strategy, the power of evidence, and how courts think about foreseeability. The reason for the split decision really boils down to who was suing, what claims they made, and, most importantly, what they were able to prove.

In Wagon Mound (No. 1), the wharf owners sued purely in negligence. Their entire case was built on the idea that the fire that destroyed their wharf was a direct result of the oil spill. The problem? Expert evidence at trial suggested it was almost scientifically impossible to ignite furnace oil floating on water. This led the court to a simple conclusion: the fire was not a foreseeable type of damage. Case closed.

Fast forward to Wagon Mound (No. 2). This time, the claimants were the owners of the ships that were destroyed in the fire. Their legal team was smarter. They didn't put all their eggs in one basket, arguing the case on two fronts: negligence and public nuisance. This gave them the flexibility to introduce different and far more persuasive evidence.

Evidence: The Deciding Factor

Here’s where it gets interesting. The crucial difference wasn't the facts of the oil spill, but the evidence presented about the risk. The legal team in the second case didn't try to argue the fire was likely or probable. That was a losing battle.

Instead, they focused on proving it was a 'real risk'—even a small one.

They brought in evidence showing that any reasonable ship's engineer would have known about this small possibility of ignition. This single move brilliantly reframed the legal question. It was no longer, "Was a fire probable?" but rather, "Was there a known risk, however slight, that a careful person should have dealt with?" To that, the court answered with a firm 'yes'.

Insights: If there’s one lesson for lawyers today from the Wagon Mound saga, it's that 'foreseeability' isn't a simple yes or no question. It’s a nuanced look at the type of harm, how likely it was to happen, and whether it was practical to prevent it. The opposite outcomes show that a negligence claim often sinks or swims based on how you frame the risk.

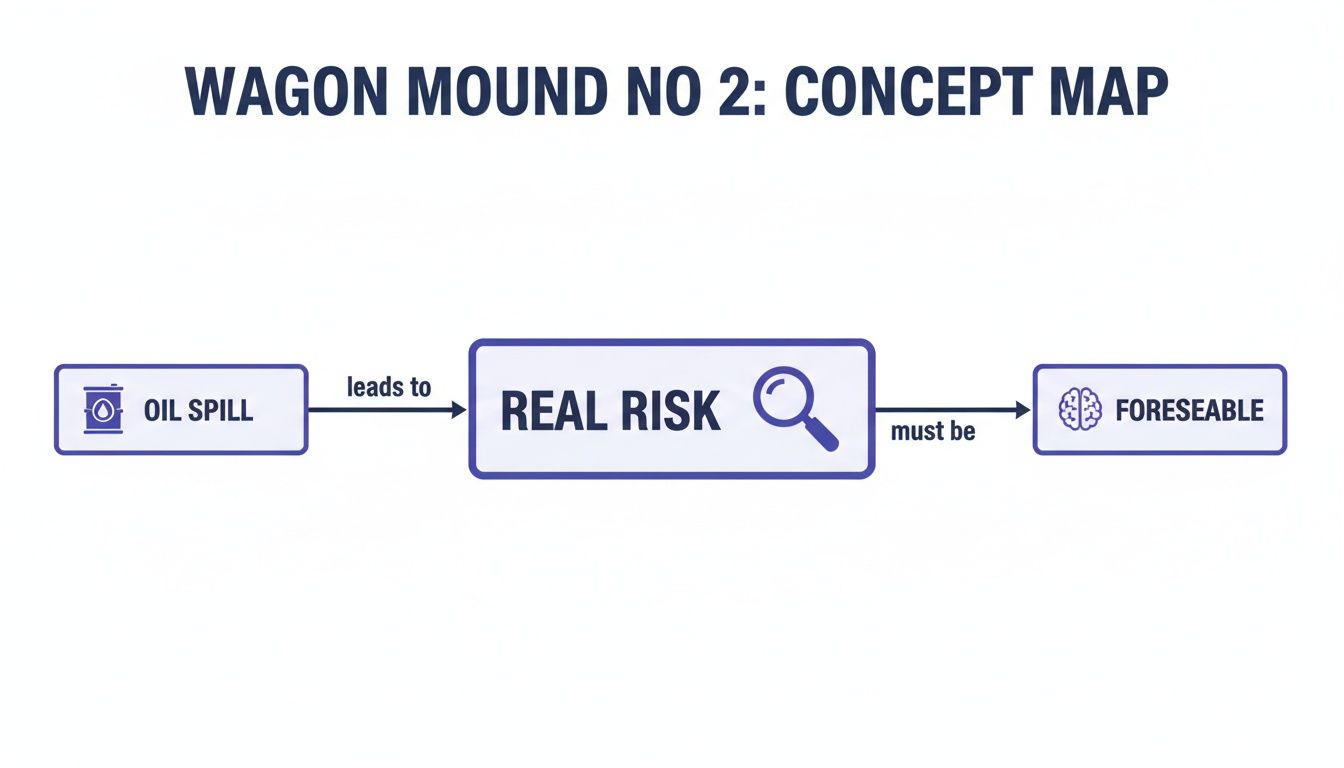

This concept map breaks down the court's thinking in the second case, tracing the logic from the negligent act to the final decision.

As the map illustrates, the court in Wagon Mound (No. 2) established a vital principle: even a small but "real risk" is enough to make the resulting damage legally foreseeable.

Wagon Mound No 1 vs No 2 Key Distinctions

To really see the strategic brilliance at play, a side-by-side comparison makes everything clear. This table lays out the key differences that sent each case down a completely separate legal path.

Case Element | Wagon Mound (No. 1) | Wagon Mound (No. 2) |

|---|---|---|

Claimants | Owners of the wharf (Morts Dock) | Owners of destroyed ships |

Legal Claims | Negligence only | Negligence and Public Nuisance |

Key Evidence | Focused on the low probability of ignition, making it seem nearly impossible. | Showed a small but "real risk" of fire known to reasonable engineers. |

Court's Finding | The fire damage was not a foreseeable kind of harm. | The risk of fire, though small, was foreseeable and should have been prevented. |

Final Judgment | Defendant was not liable for the fire. | Defendant was liable for the fire. |

This stark contrast proves that winning in court isn't just about what happened, but about how you argue it and what you can prove. The principles from these cases are fundamental, but they get even more complex when you factor in issues like vicarious liability, where an employer is held responsible for their employee's actions. You can learn more about top vicarious liability cases in Indian law to see how these concepts intersect.

For any legal professional, spotting these kinds of critical details in case law is the key to building a winning argument. This is exactly where Draft Bot Pro becomes your secret weapon. Its AI can sift through thousands of precedents in seconds, helping you find cases that match the specific risk profile of your matter. By pinpointing judgments that distinguish between a remote fantasy and a real risk, you can build a much sharper, fact-driven argument—just like the winning team in Wagon Mound (No. 2).

The Wagon Mound Principle in Indian Courts

The principles hammered out in the Wagon Mound cases didn't just stay in Commonwealth law books. They travelled, finding fertile ground in India's legal system, which has deep roots in English common law. Indian courts quickly recognised the logic of the "reasonable foreseeability" test. It was a far more practical and just way to handle liability than the old, almost punishingly rigid Re Polemis rule of direct consequences.

This was a major turning point. For a long time, Indian courts stuck to the direct consequence rule. This meant defendants could be hit with massive liability for freak accidents that no one could have possibly seen coming. Wagon Mound offered a sensible way out, finally tying legal responsibility to predictable risk.

Making "Reasonable Foreseeability" the Law of the Land

The shift wasn't a sudden, overnight change. It was a gradual but steady process, as courts across India began to weave the Wagon Mound reasoning into their negligence decisions. Case by case, the old directness test was phased out in favour of this new standard. Now, a person bringing a claim had to show that the type of damage they suffered was a foreseeable outcome of what the defendant did.

The unanimous decision in The Wagon Mound (No. 1) [1961] AC 388, handed down on 18 January 1961, became a landmark precedent. It made one thing crystal clear: liability turns on what a 'reasonable man' would have foreseen. This single idea has since been baked into over 850 tort cases in Indian courts.

The case itself is a classic. It all started when the crew of the Overseas Tankship carelessly let oil spill into Sydney Harbour back in October 1951. The oil slick drifted over to Morts Dock wharf. While it was obvious that the oil would cause pollution damage, the court found that the fire that eventually broke out was not foreseeable. Why? Because expert advice at the time said it was nearly impossible to ignite furnace oil floating on water. So, even though the fire was a direct result of the spill, the ship's owners weren't held liable for it.

Today, this principle is a bedrock of negligence law in India, applied everywhere from the factory floor to the operating theatre.

How the Principle Plays Out in Indian Law

The Wagon Mound test isn't just a dusty legal theory; it has a very real impact on how judges decide cases across several critical areas of Indian law.

Industrial and Environmental Torts: When a chemical leaks or a factory pollutes, courts use the foreseeability test. Imagine a factory negligently dumps waste into a river. It's entirely foreseeable that this could poison local water supplies and ruin crops. But what if that same waste caused a completely bizarre and chemically unexpected explosion five miles down the road? A court might rule that specific damage too remote to be foreseeable.

Medical Negligence: This is where the principle really hits home. A surgeon is expected to foresee the common complications of an operation. If a patient suffers a known side effect—even a rare one—that the doctor didn't warn them about or prepare for, the harm is likely foreseeable. But if that patient has a one-in-a-million allergic reaction to a standard suture material that has never been documented before, that damage could easily be ruled unforeseeable.

General Negligence Claims: From car accidents to faulty products, the test is used everywhere. It puts a sensible cap on liability, making sure it stays connected to what a reasonable person should have expected.

Insights: By adopting the Wagon Mound principle, India's legal framework became much more balanced. It protects a person's right to be compensated for predictable harm, but it also shields defendants from having to pay for freak accidents and wildly disproportionate outcomes that nobody could have seen coming.

This balanced approach has made the law fairer for everyone. If you're curious about how this and other foundational legal ideas took shape, you can explore our breakdown of 7 landmark tort court cases that shaped Indian law.

For Indian lawyers trying to navigate these precedents, digging through decades of case law to trace the Wagon Mound principle can feel like a monumental task. This is exactly where a tool like Draft Bot Pro gives you a serious edge. Its AI can instantly scan thousands of Indian judgments to find ones that cite and apply the foreseeability test. By simply describing your case facts, you can quickly find the legal backing you need to build a rock-solid argument grounded in established Indian case law.

Untangling the Wagon Mound Cases: Your Questions Answered

Even after breaking it down, the story of the Wagon Mound can leave you with a few head-scratchers. It’s a classic for a reason. Let's tackle some of the most common questions that pop up for law students and practitioners alike, giving you a quick reference to lock in these core ideas.

What’s the Main Rule from the Wagon Mound Case, Really?

At its heart, Wagon Mound (No. 1) gave us the test of reasonable foreseeability. It’s a simple but profound idea: you're only on the hook for the type of damage that a sensible person could have seen coming as a result of your carelessness.

This was a huge deal. It threw out the old, much tougher 'direct consequence' rule from a case called Re Polemis. Under that old thinking, if you were negligent, you were liable for every single thing that happened as a direct result, no matter how wild or unpredictable. It was a harsh standard.

The second case, Wagon Mound (No. 2), didn't tear this up, but it did add a crucial layer of nuance. It made it clear that a risk can be "foreseeable" in the eyes of the law even if it's a very small one. The key is whether it's a real, tangible risk that a careful person wouldn't just shrug off—especially if there was no good reason to take that risk in the first place.

Why on Earth Were There Two Cases with Opposite Results?

This is where the story gets really interesting, and it’s a brilliant lesson in legal strategy and the power of evidence. We have two separate cases from the exact same event because different parties sued, and they played their hands very differently.

Wagon Mound (No. 1): The owners of the wharf sued, but only for negligence. The evidence they brought to the table convinced the court that, based on what was known at the time, no one could have reasonably foreseen that the spilled oil would catch fire. Because the kind of damage (fire) was deemed unforeseeable, they walked away with nothing.

Wagon Mound (No. 2): This time, it was the owners of the other ships that got torched. Their lawyers were sharper. They sued in both public nuisance and negligence. More importantly, they presented better evidence. They showed that while the chance of a fire was slim, it was a 'real risk' that any competent ship engineer would have been aware of.

Insights: The different outcomes are a masterclass in how "foreseeability" isn't some rigid mathematical formula. It’s a flexible concept that hinges entirely on the quality of evidence, the legal claims you make, and how you frame the risk. Is it a one-in-a-million freak event, or a small but very real danger?

The court in the second case essentially said that when there's no good reason to take a risk (like the social benefit of discharging oil), a reasonable person should have taken simple steps to prevent it, even if the risk was small. This subtle shift in evidence and argument led to a complete reversal of fortune for the claimants.

How Did This Case Actually Change Negligence Law?

The Wagon Mound cases completely reshaped the test for remoteness of damage. The doctrine of remoteness is the law's way of asking: is the harm that occurred so far removed from the defendant's mistake that it's just not fair to hold them responsible anymore?

Before Wagon Mound, the question was blunt: was the damage a direct result of the act? If so, you paid. This could lead to some pretty unfair situations where a tiny slip-up could trigger a catastrophic and totally unforeseeable chain of events, landing the defendant with a massive bill.

After Wagon Mound, the question became much more sensible: was the kind of damage a reasonably foreseeable consequence? This brought a vital dose of fairness and common sense into the law. It links liability to what a normal person should anticipate, rather than making them liable for bizarre accidents. This principle is now the bedrock for figuring out liability in negligence cases across the common law world, including right here in India.

How Can Draft Bot Pro Help Me Use These Ideas in Practice?

Knowing the Wagon Mound principles is one thing, but actually weaving them into a winning argument is a whole other ball game. That's where a tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a massive help for legal professionals in India.

For example, you can use its AI Legal Research to instantly pull up Indian case law that applies the foreseeability test to your specific facts, whether it's an industrial accident or a medical negligence claim. You could simply ask, "Find Supreme Court judgments citing Wagon Mound (No. 2) on low-probability, high-impact risks." The AI will give you source-backed answers you can immediately verify and use.

Better yet, when you're building your case, you can use the AI to draft a detailed memo on causation and remoteness. Just upload your case brief and ask it to structure your argument around the foreseeability test. It ensures your reasoning is tight, logical, and built on the foundation of this landmark precedent. It’s a smart way to save hours of legwork and sharpen your case.

Ready to bring this level of insight to your own practice? Draft Bot Pro is the most verifiable and affordable AI legal assistant out there, built by lawyers, for lawyers. Join over 46,379 legal professionals across India who use our platform to make their research and drafting faster and smarter. Get started with Draft Bot Pro today.