A Practitioner's Guide to Section 21 CPC

- Rare Labs

- Dec 15, 2025

- 17 min read

At its heart, Section 21 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) is about fairness and finality. Think of it as a "speak now or forever hold your peace" rule for jurisdictional challenges. It basically says that if you think a case has been filed in the wrong court—either geographically or based on its monetary value—you have to raise that objection right at the beginning. If you don't, you lose the right to complain about it later.

Decoding the Core Rule of Section 21 CPC

Imagine you're playing a cricket match. You play the entire game, the final runs are scored, and only after your team loses do you argue that the umpire wasn't authorised to officiate at that specific ground. It just wouldn't fly. Any objection like that needed to be raised before the first ball was bowled.

Section 21 of the CPC applies this exact logic to civil lawsuits in India. It’s a procedural safeguard to stop parties from using jurisdictional challenges as a sneaky, last-ditch tactic to get an unfavourable judgment thrown out.

The whole idea is built on the concept of acquiescence. When you participate in court proceedings without protest, you’re implicitly agreeing that the court has the authority to hear the case, at least as far as its location (territorial jurisdiction) or the suit’s value (pecuniary jurisdiction) is concerned. This prevents the legal system from getting bogged down by technical objections raised simply to delay justice.

The 'Raise It or Waive It' Doctrine

The message of Section 21 is crystal clear: if you believe a lawsuit is in the wrong court, you need to say so immediately. This isn't just good practice; it's a strict procedural requirement. The law insists that this objection must be made at the "earliest possible opportunity" and, in any case, at or before the issues in the suit are framed.

If you miss this window, the consequences are serious. The law considers the objection waived. You can't just bring it up for the first time when you're appealing a decision you don't like. This stops a losing party from springing a surprise jurisdictional attack after having fully participated in the trial.

Key Phrases Explained

To really get a handle on Section 21, let's break down its crucial parts:

Place of Suing: This is all about the court's territorial or pecuniary limits. It has nothing to do with whether the court has the inherent power to even hear a case of that type (which is called subject-matter jurisdiction).

Earliest Possible Opportunity: This is usually your first real chance to respond, which for a defendant means raising the point in their written statement.

Consequent Failure of Justice: This is the big exception. Even if you raised the objection late, an appellate court might still hear it, but only if you can prove that holding the trial in the wrong court actually caused a "failure of justice." This is a very, very high bar to clear.

Section 21 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC), a cornerstone of Indian civil litigation, dictates that objections to the place of suing must be made at the first available instance. Failure to do so means the objection is waived, unless it has caused a genuine failure of justice. This provision, enacted on March 21, 1908, is more relevant than ever. In fact, Supreme Court data from 2018-2019 showed that jurisdictional challenges under this section featured in roughly 15% of civil appeals. You can learn more about the history of objections to the place of suing.

InsightsThe philosophy behind Section 21 is about distinguishing between a court that has zero power to hear a case and a court that is simply the wrong venue. A mistake in territorial jurisdiction is seen as a procedural hiccup that a party can agree to waive, not a fundamental flaw that makes the whole process void from the start.

For any lawyer today, keeping these timelines straight is non-negotiable. This is where modern legal tech gives you a real edge. An AI-powered tool like Draft Bot Pro can be your safety net. As you draft your written statement, it can cross-reference the case details with jurisdictional rules, flagging potential territorial or money-value issues early on. This helps you raise timely objections and avoid an accidental waiver that could cost your client the case down the road.

Quick Guide to Objections Under Section 21 CPC

Navigating the timelines and conditions for raising jurisdictional objections can be tricky. This table breaks down the essentials of Section 21 into a simple, easy-to-reference format for busy practitioners.

Type of Objection | When to Raise It | Condition for Appellate or Revisional Interference |

|---|---|---|

Territorial Jurisdiction | At the earliest possible opportunity, and always at or before the settlement of issues. | The objection was raised at the earliest opportunity, AND there has been a consequent failure of justice. |

Pecuniary Jurisdiction | At the earliest possible opportunity, and always at or before the settlement of issues. | The objection was raised at the earliest opportunity, AND there has been a consequent failure of justice. |

Jurisdiction of Executing Court | Objection must be raised in the executing court at the earliest possible opportunity. | The objection was raised in the executing court, AND there has been a consequent failure of justice. |

Remember, the 'failure of justice' clause is the key hurdle for an appellate court to even consider a belated objection. Without it, the waiver rule is absolute.

The Three Conditions for Challenging Jurisdiction

So, you've spotted a potential jurisdictional error in a case. That's a great start, but it's not enough to get a decree overturned on appeal. Section 21 of the CPC lays down a tough, three-part test that an appellate or revisional court must follow before it even considers an objection to the place of suing.

Think of these conditions as three locked gates in a row. You need the right key for all three to get through. Fail on just one, and your objection is dead in the water.

This high bar is intentional. It reinforces the system's preference for substance over procedural nitpicking. The law wants to prevent parties from losing on merits and then trying to use a jurisdictional argument as a last-ditch escape hatch.

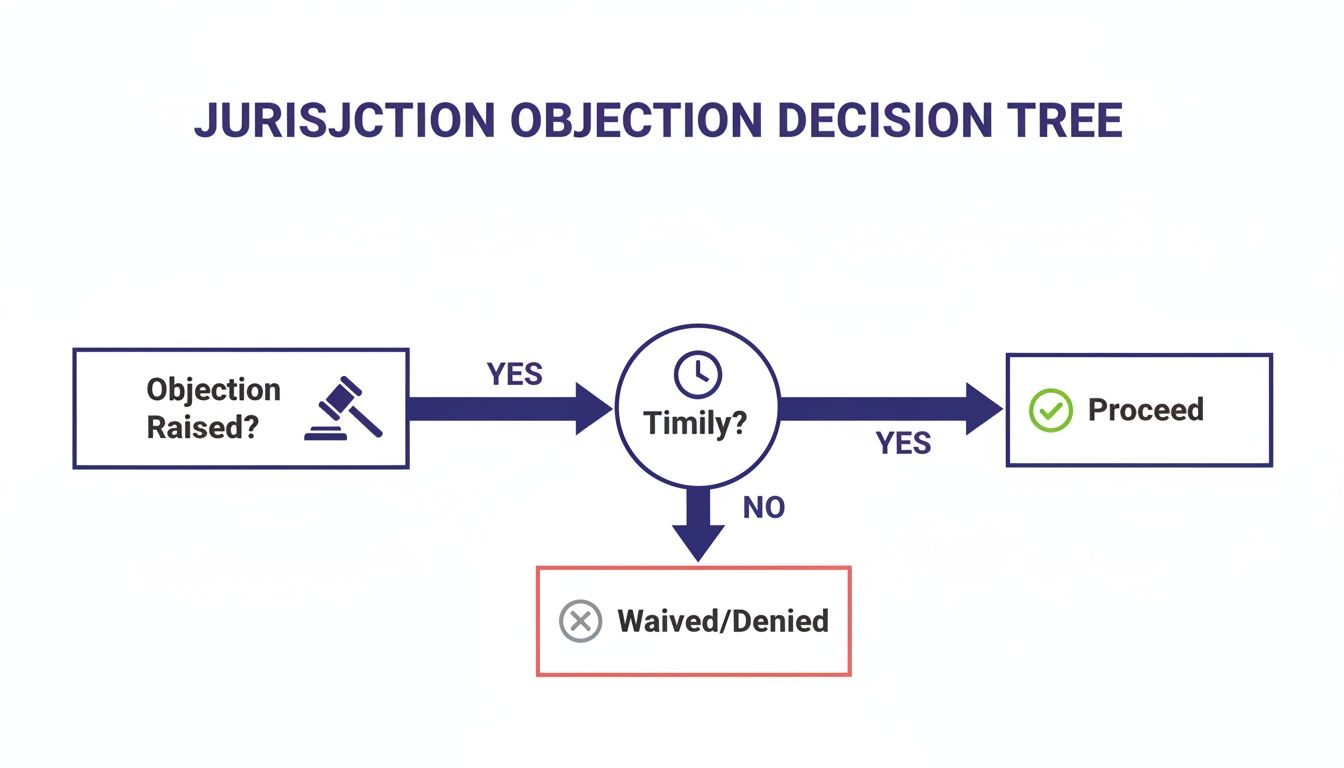

This decision tree shows you exactly how a court walks through the process when faced with a jurisdictional challenge under Section 21.

As you can see, a 'no' at any point stops the entire inquiry. This really drives home how crucial it is to raise these objections right at the beginning of a suit.

Condition 1: The Objection Was Raised in the Trial Court

First and foremost, you can't bring up a jurisdictional issue for the first time on appeal. The objection absolutely must have been raised in the original court—the court of first instance.

The logic here is simple: if you didn't challenge the court's territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction during the trial, you've essentially agreed to it by your conduct. The appellate court won't let you spring a new argument that should have been sorted out from day one. This gives the trial court the first crack at deciding its own jurisdiction.

Condition 2: The Objection Was Raised Timely

This condition builds on the first one. It’s not enough to just raise the objection in the trial court; you have to do it at the "earliest possible opportunity." The CPC pins this down precisely: at or before the settlement of issues.

The settlement of issues is that critical stage where the court crystallises the main points of contention. Bringing up jurisdiction before this happens allows the court to deal with it as a preliminary issue, potentially saving everyone a massive amount of time and money. If you wait until after the issues are framed, your objection is almost certainly doomed.

Condition 3: There Was a Consequent Failure of Justice

This last condition is the highest hurdle. Even if you checked the first two boxes—you raised the objection in the trial court and you did it on time—the appellate court still won't step in unless you can prove a "consequent failure of justice."

This is a very high standard. We're not talking about mere inconvenience or extra travel costs. A "failure of justice" means you have to show that holding the trial in the wrong court caused you real, tangible prejudice that fundamentally damaged your ability to fight your case.

Let's look at a couple of scenarios:

Example 1 (Not a Failure of Justice): A defendant from Delhi gets sued in Mumbai. They argue that travelling for hearings was expensive and a hassle. This argument will almost certainly fail. Courts see this as a manageable inconvenience, not a fundamental denial of justice.

Example 2 (Potential Failure of Justice): A defendant in a property dispute in a remote village is sued in a far-off metro city. They argue that their key witnesses—elderly villagers with no way to travel—couldn't testify. This meant they were deprived of crucial evidence. This has a much stronger chance of being considered a "failure of justice" because it directly impacted the merits and outcome of the case.

The Supreme Court's 2019 decision in Om Prakash Agrawal v. Vishan Dayal Rajpoot hammered this point home. The court held that Section 21 CPC is an express bar, stopping appellate courts from reversing a decree on jurisdictional grounds unless the objection was timely and there was a proven failure of justice. This stance has had a real impact; of the roughly 1.2 lakh civil appeals involving Section 21, data shows 79% were dismissed due to this waiver, helping clear judicial backlog. You can explore more insights on this landmark judgement and its effect on civil procedure.

InsightsProving a "failure of justice" is all about evidence. You can't just assert it. You must draw a direct line connecting the wrong jurisdiction to a negative impact on the merits of your case.

This is where having the right tools makes a difference. When you need to prove a failure of justice, you have to find precedents with similar facts. Draft Bot Pro’s advanced case analysis feature can scan thousands of judgements in moments, finding cases where courts have defined "failure of justice" in situations just like yours. By arming you with these specific precedents, it gives you the legal ammunition you need to build a truly persuasive argument on appeal.

Landmark Judgements That Define Section 21

The black-and-white text of a law gives us the blueprint, but its true character is forged in the courtroom. For Section 21 of the Code of Civil Procedure, it's the landmark judgements from the Supreme Court of India that have chiselled its meaning, clarifying how it works in the real world and reinforcing its core purpose. These rulings trace a clear judicial line of thought: substantial justice must always win out over procedural technicalities, especially when a jurisdictional objection feels like a last-ditch, tactical move.

By digging into these crucial cases, we can get a solid grip on the principles that guide courts when they’re faced with challenges to territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction. The consistent theme? A flat-out refusal to let litigation get derailed by objections that could—and should—have been raised right at the start.

The Foundation: Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd.

One of the most foundational cases that shaped how we understand Section 21 is Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd., (2005) 7 SCC 791. This case drew a bright, unmissable line between different kinds of jurisdictional mistakes.

The Supreme Court made it crystal clear that objections about territorial and pecuniary jurisdiction are in a completely different league from objections to a court's inherent subject-matter jurisdiction. The Court held that while a decree passed by a court that fundamentally lacks the power to hear a case (subject-matter jurisdiction) is a total nullity and can be challenged anytime, anywhere, a decree from a court with a mere defect in its territorial or pecuniary scope is not automatically void. It's merely voidable. This is a critical distinction. It means a party can, through their actions or even their silence, waive their right to object to the place of suing.

Reinforcing the Waiver Principle in Pathumma v. Kuntalan Kutty

Building on that foundation, the case of Pathumma v. Kuntalan Kutty, (1981) 3 SCC 589 hammered home the waiver principle that sits at the very heart of Section 21 CPC. Here, the Supreme Court emphasised that a party who jumps into the proceedings without a word of protest can't suddenly turn around and challenge the court's jurisdiction just because the outcome wasn't in their favour.

The ruling drove home the point that Section 21 is basically a statutory nod to the principle of estoppel. By submitting to the court’s authority and rolling the dice on a favourable verdict, a party is effectively barred from questioning that same authority later. This stops defendants from keeping a jurisdictional "ace up their sleeve" to play only if they lose the case on its merits.

This approach was cemented further in a pivotal 2019 Supreme Court ruling. In a judgement from January 7, 2019, the Court meticulously applied Section 21 to a title suit. It noted that even though the defendant had correctly raised an objection to territorial jurisdiction in their written statement, their failure to show up later led to an ex-parte decree. The objection ultimately failed because the strict conditions of Section 21—especially the "consequent failure of justice" part—were not met.

InsightsThe judicial philosophy here is not hard to see. Courts look at delayed jurisdictional objections with a healthy dose of scepticism, often seeing them as potential tools for dragging out litigation. The goal is simple: once a trial has been fought and won on its merits, the result shouldn't be easily overturned by procedural arguments that should have been sorted out from day one.

Keeping up with this web of case law can be a real challenge. An AI legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro is designed to cut through the complexity. Its legal research feature can instantly pull up summaries and analyses of these key judgements, helping you quickly grasp the core principles. By giving you context and precedent, it makes sure your arguments are built on solid ground, reflecting the latest judicial thinking on Section 21.

Key Precedents on Section 21 CPC

To really navigate Section 21 effectively, you need to understand how the Supreme Court has interpreted it over the years. This table gives you a quick snapshot of the core principles laid down by these landmark cases.

Case Name | Year | Core Principle Established |

|---|---|---|

Harshad Chiman Lal Modi v. DLF Universal Ltd. | 2005 | A decree passed by a court with defective territorial jurisdiction is merely voidable, not a nullity. Objections are waivable. |

Pathumma v. Kuntalan Kutty | 1981 | A party who willingly participates in proceedings is estopped from later challenging the court’s territorial or pecuniary jurisdiction. |

These judgements, and others like them, have built a strong framework for applying Section 21. They all send the same message: timely and diligent compliance with procedure matters.

If you find this area of law interesting, you might also want to check out our guide on other top landmark judgements of the Supreme Court of India. It will give you a broader perspective on how judicial precedent shapes legal practice across different fields.

How to Draft a Jurisdictional Objection

Knowing the law is one thing; putting it into practice is where cases are won and lost. Drafting a solid jurisdictional objection under Section 21 of the CPC isn't just a procedural formality. It's a strategic first strike that can define the entire battleground for your case. Get it right—and raise it at the earliest possible moment in your written statement—and you can control the narrative from day one.

This objection is your formal protest. It puts both the court and the plaintiff on notice that you're challenging their choice of venue. It has to be sharp, precise, and firmly rooted in the facts of the case. Fumble this, or file it too late, and you might find you’ve accidentally given up one of your most powerful defensive tools for good.

The Anatomy of an Effective Objection

When you're drafting that preliminary objection, ambiguity is your enemy. Vague, wishy-washy statements will get you nowhere. You need to be crystal clear about why the court can't hear the suit—is it territorial, pecuniary, or something else?—and connect it directly to the facts laid out in the plaint.

Here’s a basic framework you can build on:

Sample Jurisdictional Objection Paragraph:"PRELIMINARY OBJECTION: The Defendant submits that this Hon’ble Court lacks the territorial jurisdiction to entertain and try the present suit. The cause of action, as alleged in the plaint, arose entirely in [City/District], and the Defendant also resides and works for gain in [City/District]. Therefore, under Sections 16 to 20 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, the suit ought to have been instituted in the competent court at [City/District]. The filing of the suit before this Hon'ble Court is a misuse of the process of law, and it ought to be returned to the Plaintiff for presentation before the proper court."

This example nails three crucial things:

It’s clearly labelled as a "Preliminary Objection," so the court can't miss it.

It specifies the exact type of jurisdiction being challenged (territorial).

It gives a concise factual reason for the challenge and points to the correct court.

Strategic Drafting Considerations

Beyond the wording, think about the strategy. Your goal is to force the court to decide on jurisdiction before diving into the merits of the actual dispute. If you succeed, you could get the plaint returned under Order VII Rule 10 of the CPC, which can save your client a massive amount of time, money, and stress.

So, your draft needs to be assertive. Frame the objection not as a polite suggestion, but as a fundamental barrier that stops the court from proceeding any further. This makes the judge sit up and take the issue seriously.

To really drive the point home, consider filing a separate application to frame a preliminary issue on jurisdiction. The objection lives in your written statement, but a dedicated application puts the issue front and centre, pushing the court to deal with it first. For tips on bolstering your applications, check out our guide on preparing an affidavit under CPC in India.

InsightsHere's a critical distinction every lawyer must know: the difference between a waivable defect and an inherent lack of jurisdiction. Section 21 deals with waivable issues like territorial or pecuniary limits. But if a court lacks inherent subject-matter jurisdiction (like a civil court trying to hear a case meant exclusively for a consumer forum), that's a whole different ball game. You can raise that objection at any stage—even during execution—because the entire proceeding is considered void from the very beginning (ab initio).

Leveraging AI for Precision Drafting

In the chaotic world of litigation, it's easy to make a small procedural slip-up. An awkwardly phrased preliminary objection could be dismissed as vague, or worse, be seen as a waiver of your right to object. This is exactly where modern tools can give you an edge.

A legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro is perfect for this. You can upload the plaint and instruct the AI to generate a precise preliminary objection based on the facts provided. It will formulate the correct legal language required by the CPC, ensuring your objection related to Section 21 of the CPC is perfectly structured and procedurally sound. It's not just about saving time; it's about adding a layer of protection against a simple mistake that could derail your entire case.

Common Mistakes to Avoid with Section 21

When it comes to Section 21 of the Code of Civil Procedure, precision is everything. Even seasoned advocates can slip into procedural traps that can seriously undermine their case, or worse, make them waive a crucial right without even realising it.

Knowing these common pitfalls is the first step to building a solid, mistake-free litigation strategy right from the get-go.

Think of this section as your practical checklist. We'll walk through the most frequent errors and give you clear-cut strategies to sidestep them. By spotting these potential stumbles before they happen, you can make sure your arguments on jurisdiction are always on time, well-founded, and effective.

Confusing Subject-Matter with Territorial Jurisdiction

This is one of the most basic yet surprisingly common mistakes: mixing up a court's inherent jurisdiction with its territorial or pecuniary limits. Section 21's "raise it or waive it" rule only applies to the latter two. It's completely powerless against an objection to subject-matter jurisdiction.

The Mistake: Imagine a defendant fights a whole trial in a civil court for a matter that, by law, should only be heard by a specialised body like the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). After losing, they try to raise the jurisdiction point for the first time on appeal.

The Consequence: While the waiver rule of Section 21 CPC shuts the door on late territorial challenges, a lack of subject-matter jurisdiction makes the entire decree a nullity—a complete waste of everyone's time. Confusing the two leads to weak arguments and wasted efforts.

Avoidance Strategy: Make this a non-negotiable first step in your case analysis: always confirm the court’s subject-matter competence. Do this before you even start thinking about territorial or financial limits.

Missing the "Earliest Possible Opportunity"

The timeline for objecting to jurisdiction isn't just a friendly suggestion; it's a hard deadline. The CPC is crystal clear: you must raise your objection at or before the settlement of issues. Waiting a day longer is often fatal.

InsightsCourts treat the settlement of issues as the point of no return for preliminary objections like jurisdiction. Once the parties and the court have locked in the core points of dispute, the law assumes all procedural preliminaries have been either settled or given up.

The Mistake: A defendant files their written statement but forgets to include a specific paragraph challenging the court's territorial jurisdiction. Later on, they realise the slip-up and try to amend their pleading or just mention it orally.

The Consequence: The court will almost certainly rule that the objection has been waived. Just like that, the defendant loses their right to challenge the place of suing, not just in the trial court but on appeal as well.

Avoidance Strategy: Add jurisdictional analysis to your mandatory pre-drafting checklist for every written statement. It's just as important as addressing the merits. Getting these procedural steps right is as vital as ensuring proper service of summons, a topic you can dive into deeper in our complete guide.

Underestimating the 'Failure of Justice' Hurdle

Here’s another classic slip-up: thinking that just showing some inconvenience is enough to prove a "consequent failure of justice." The courts have set an incredibly high bar for this test. The cost or difficulty of travelling to court simply won't cut it.

The Mistake: On appeal, a lawyer argues that a failure of justice occurred because their client had to travel from Mumbai to Delhi for the trial. But they don't provide any proof of how this travel specifically stopped them from properly presenting their case.

The Consequence: The appellate court will toss that argument out. Without solid proof that the wrong venue caused real prejudice—like being unable to bring a key witness to court or produce crucial evidence—the objection is doomed to fail.

Avoidance Strategy: If you have to argue "failure of justice," you need to build a strong foundation of evidence. You must show a direct, causal link between the incorrect jurisdiction and a tangible, negative impact on the trial's final outcome.

In the fast-paced world of legal practice, these mistakes can happen to anyone. This is where an AI legal assistant like Draft Bot Pro acts as an essential safety net. It can help flag procedural deadlines and ensure preliminary objections under Section 21 CPC are correctly drafted and included in your written statement from the very beginning, preventing these critical oversights.

Common Questions About Section 21 CPC

When you're deep in the trenches of civil litigation, procedural questions always pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common queries that lawyers have about Section 21 of the CPC, with clear, practical answers to help you in your day-to-day practice.

Getting these concepts right from the very beginning can make or break your litigation strategy.

Territorial vs. Subject Matter Jurisdiction

One of the first hurdles is understanding the difference between territorial and subject-matter jurisdiction. It's a crucial distinction. The waiver rule in Section 21 CPC is very specific: it only applies to objections about territorial (the geographical location) and pecuniary (the monetary value) jurisdiction. Think of these as procedural technicalities that a party can accidentally (or intentionally) waive through their actions.

Subject-matter jurisdiction, on the other hand, is a completely different beast. This is about the court's fundamental power to even hear a certain type of case. An objection here isn't just a procedural point; it goes to the very root of the court's authority. A court that lacks subject-matter jurisdiction can't issue a valid order, period. That’s why you can raise this objection at any stage—even during execution proceedings—because any decree passed is considered a complete nullity from day one.

Does This Apply to Arbitration?

A great question. Does the spirit of Section 21 carry over into arbitration proceedings? While the Code of Civil Procedure doesn't directly rule over arbitration, its core principles—especially waiver and estoppel—are incredibly influential.

The courts have been pretty consistent on this. If a party jumps into arbitration proceedings without raising a fuss about the location at the first opportunity, they're generally barred from crying foul later on. It’s the same "speak now or forever hold your peace" principle from Section 21, which pushes for finality and stops parties from trying to get a second bite at the apple just because they didn't like the award.

What Exactly is a 'Failure of Justice'?

This is where many lawyers get tripped up. Is it enough to show that having the trial in the "wrong" court was a massive inconvenience? The judiciary's answer has been a resounding "no."

A Word from the WiseThe courts have made it clear that simple inconvenience—like the hassle and cost of travel—doesn't come close to the high bar of a 'consequent failure of justice'. The prejudice you claim has to be real, substantial, and hit the core merits of your case.

To win this argument, you have to show actual, tangible harm that warped the outcome. For example, you’d need to prove that the trial's location made it impossible for you to bring a key piece of evidence to court or to get a crucial witness to testify. You have to connect the dots and show how this logistical issue directly sabotaged your ability to fight your case effectively.

Missed the Deadline? Can Legal AI Still Help?

So, you've missed the boat and the deadline to object has passed. What now? This is where legal tech can become your secret weapon. A tool like Draft Bot Pro can't time-travel and fix a missed deadline, but its powerful research capabilities can be a game-changer for your appeal strategy.

Just because you're facing a waiver doesn't mean it's game over. Draft Bot Pro can comb through mountains of legal databases in minutes to find that one obscure precedent or specific judicial observation where a court took a softer stance on what counts as a "failure of justice." It can help you find those rare exceptions that could give you a fighting chance on appeal, forming a legal foundation for an argument that might otherwise seem impossible.

Ready to build stronger, more precise legal arguments? Discover how Draft Bot Pro can support your legal research and drafting needs by visiting https://www.draftbotpro.com.