A Practical Guide to Section 448 IPC and House-Trespass

- Rare Labs

- Dec 6, 2025

- 17 min read

When you hear "trespass," you might picture someone hopping a fence into a field. But Section 448 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) deals with something far more serious: house-trespass. This isn't just about being on someone's property without permission; it's about violating the sanctity of their home.

The law basically says that a person's home is their castle, and an unauthorised entry into that space, especially with bad intentions, is a significant offence. It's the law's way of protecting the safety and privacy we all expect within our own four walls.

The Two Pillars of Section 448 IPC

To really get a grip on house-trespass, you need to understand that it's built on two core legal ideas. Just like a building needs a solid foundation, a charge under Section 448 IPC needs both these pillars to stand up in court. If the prosecution can't prove both, the case collapses.

Let's break them down.

Actus Reus: The Physical Act

First up is the actus reus, a Latin term that simply means the "guilty act." This is the physical part of the crime. For house-trespass, the actus reus is the physical entry into, or unlawfully remaining in, a property that is a:

Building, tent, or vessel used as a human dwelling.

Place of worship.

Building used for storing property.

The key word here is unauthorised. Pushing open a locked door is a classic example. But even just walking into someone's home without permission or staying put after you've been asked to leave can be enough to establish the physical act.

Mens Rea: The Guilty Mind

This is where things get interesting. The second pillar is the mens rea, or the "guilty mind." It's not enough to just be in the house; the law wants to know why you were there. What was your intention?

Simply making a mistake isn't a crime. If a pizza delivery guy walks into the wrong flat because the doors look identical, he's committed the physical act but lacks the crucial criminal intent.

InsightsThe 'intent' is almost always the main battleground in a Section 448 case. The prosecution has the heavy burden of proving, beyond any reasonable doubt, that the accused entered the property specifically to commit an offence, or to intimidate, insult, or annoy the person living there. Without solid proof of this guilty mind, the whole case can fall apart.

So, if someone barges into a house to threaten the family inside, you have both the physical act (actus reus) and the criminal intent (mens rea). That's a textbook case of house-trespass.

Nailing down the presence or absence of intent is everything for lawyers handling these cases. When framing a complaint or drafting a defence, you have to hit this point hard. This is where a Legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. It helps you structure your arguments to precisely target both the physical act and, more importantly, the mental element, even suggesting relevant case law to back up your claims. Getting these fundamentals right is the first step to building a strong case.

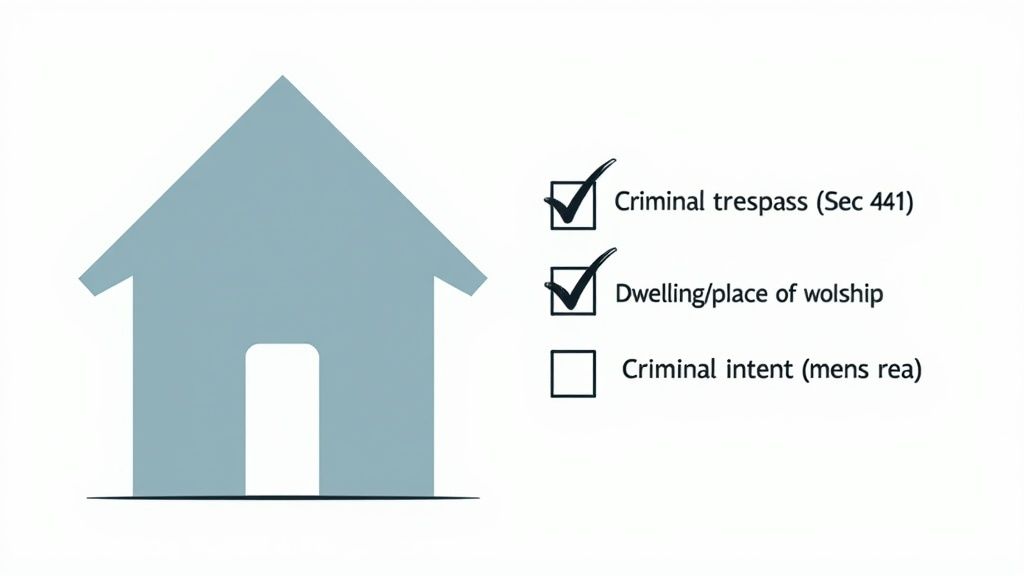

The Essential Ingredients for a House-Trespass Charge

For a charge under Section 448 IPC to stick, the prosecution needs to prove a very specific set of legal conditions. Think of it like a recipe—miss even one ingredient, and the final dish, a conviction, just won't come out right.

This is far more than just a simple accusation. The court demands clear evidence, proving every component of the offence beyond a reasonable doubt. Let's break down what that practical checklist actually looks like.

Ingredient 1: The Act Must Be Criminal Trespass

The entire case for house-trespass is built on the foundation of criminal trespass, as laid out in Section 441 of the IPC. This means the entry wasn't just unauthorised; it was done with a specific guilty intent.

The entry must have been made with the goal of:

Committing another offence inside the property.

Intimidating the person in possession.

Insulting the person in possession.

Annoying the person in possession.

Without this crucial criminal intent, a simple act of civil trespass can't be elevated to a criminal charge under Section 448 IPC.

Ingredient 2: The Location Is Specific

The second critical ingredient is all about where the trespass happened. Section 448 IPC isn't a blanket provision for any property. It's specifically designed to protect places that hold a special significance.

The trespass must occur within a structure that is:

A Building, Tent, or Vessel Used as a Human Dwelling: This is the usual scenario, covering homes, flats, and even temporary shelters where people live.

A Place of Worship: This includes any temple, mosque, church, or building set aside for religious services.

A Building Used for Storing Property: This covers places like godowns, vaults, or secure storerooms where valuables are kept.

Entering an open field or a half-built structure without permission might still be criminal trespass under a different section, but it won’t meet the specific location test for a house-trespass charge.

InsightsProving criminal intent is notoriously difficult, which is a major reason why many Section 448 IPC cases fall apart in court. The burden is entirely on the prosecution to show what was in the accused's mind, and circumstantial evidence often falls short of the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard.

Ingredient 3: Proving the Criminal Intent

This final element is often the toughest nut to crack and is where most cases are won or lost. The prosecution must definitively prove the trespasser’s specific criminal mens rea (guilty mind) at the very moment of entry. It's not enough to show they just entered without permission; the reason they entered is everything.

For instance, if two neighbours are locked in a property dispute and one enters the other's house to argue, a defence lawyer could argue the intent was simply to resolve the dispute, not to intimidate or annoy. This nuance can turn a criminal case into a civil matter in the court's eyes, which is why judicial scrutiny here is so high.

A quick look at case law shows that convictions under Section 448 IPC are relatively low. A 2019 study pointed out that only about 28% of such cases led to a conviction, often because of the high bar for proving criminal intent, especially in messy family or property disputes. You can dive deeper into these judicial trends by exploring the full findings from the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

When you're building a case, a Legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a massive help. It assists in structuring complaints and legal notices by forcing you to focus on these three essential ingredients. This ensures the facts you present clearly establish the act of criminal trespass, the specific location, and most importantly, the criminal intent needed for a solid prosecution under section 448 ipc.

Punishment and The Procedural Maze of Section 448 IPC

When you're dealing with a charge under Section 448 IPC, knowing the potential penalties and the legal roadmap ahead is absolutely critical. Once the core elements of the offence are on the table, the conversation naturally shifts to the punishment and the procedural labyrinth that every case must navigate.

The penalty for house-trespass is laid out quite clearly. If convicted, a person could be looking at:

Imprisonment for a term that could go up to one year.

A fine that can be as high as one thousand rupees.

Or, at the court's discretion, both.

But while the punishment might seem straightforward, the legal journey from the first accusation to a final verdict is anything but. It's a process governed by specific classifications that dictate how the police and courts handle the matter right from the get-go.

Understanding the Procedural Classifications

An offence under Section 448 IPC is tagged with certain procedural labels that are hugely important. These tags define the powers of the police and the rights of the accused, shaping the immediate aftermath once an FIR is filed.

First, this offence is cognizable. What does that mean in simple terms? It gives the police the power to arrest a person accused of house-trespass without needing a warrant. This tells you the law sees the violation of a person's home as serious enough to justify immediate police action, preventing any further trouble.

Second, the offence is bailable. This is a massive plus for the accused. It means they have a right to be released on bail, whether from the police station or the court, just by providing a bail bond. Unlike non-bailable offences where getting bail is up to the judge's discretion, here it's an entitlement. For anyone in this situation, knowing how to properly draft and file a bail application is key. You can get up to speed with our guide on how to master the bail application format for quick filing.

Finally, the offence is triable by any Magistrate. This simply means the case will be heard by a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class or a Metropolitan Magistrate, which pinpoints the specific court where the trial will unfold.

To make this crystal clear, here’s a quick summary of the procedural DNA of a Section 448 IPC case.

Procedural Classification of Section 448 IPC

Attribute | Classification | Implication |

|---|---|---|

Police Power | Cognizable | The police can arrest the accused without a warrant from a court. |

Bail Status | Bailable | The accused has a right to be released on bail. |

Jurisdiction | Triable by any Magistrate | The case will be heard in the court of a Magistrate of the First Class. |

This table neatly lays out the core procedural aspects that define the initial handling and legal pathway for a house-trespass charge.

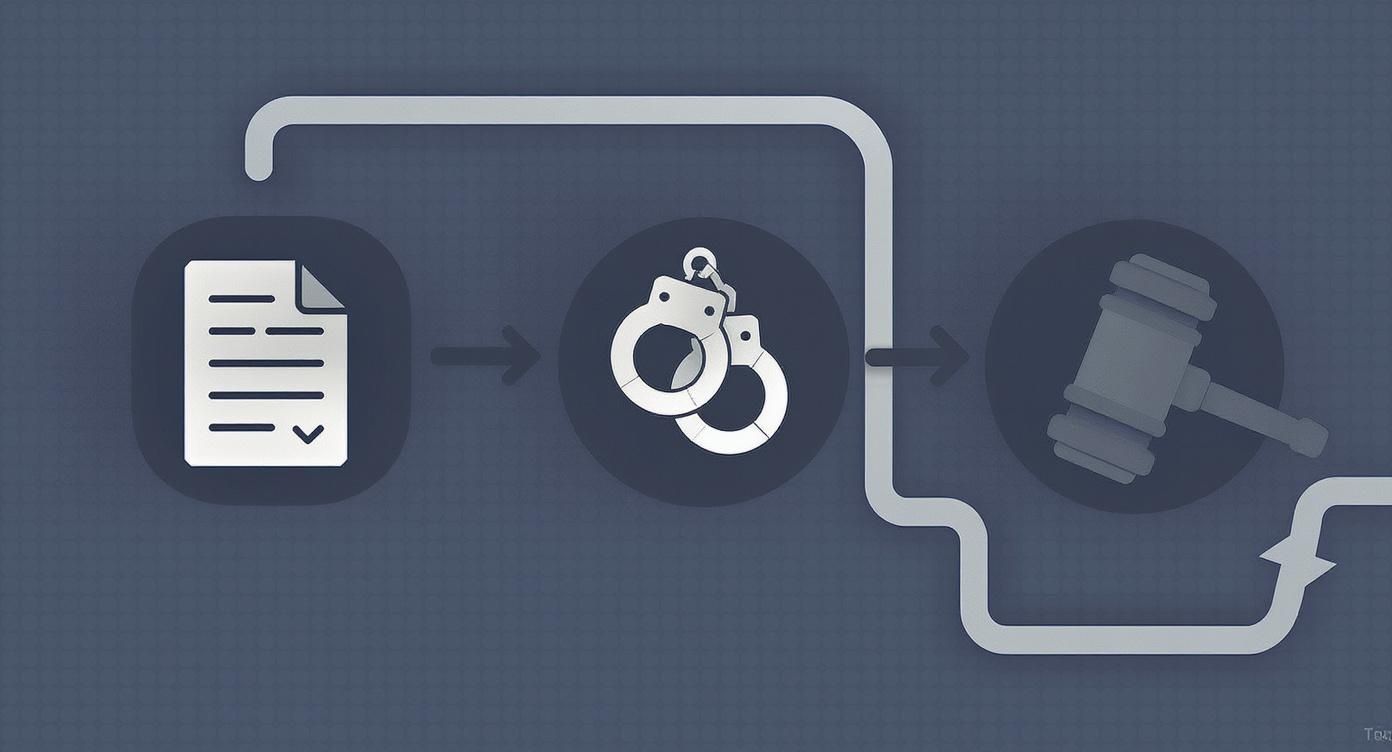

The Journey of a Section 448 Case: From FIR to Judgment

The legal process for house-trespass isn't a single event; it's a structured journey. Here’s a look at the typical roadmap:

The Starting Gun: Filing a Complaint/FIR: It all kicks off when the victim files a First Information Report (FIR) with the police or, alternatively, a private complaint directly with a Magistrate.

Investigation: Because it’s a cognizable offence, the police launch an investigation. They’ll visit the scene, gather evidence, and take statements from witnesses and the accused.

The Chargesheet: If the police believe they have enough evidence, they compile everything into a chargesheet (or final report) and file it before the appropriate Magistrate’s court.

Framing the Charges: The Magistrate then pores over the chargesheet. If it looks like there’s a genuine case to answer (a prima facie case), charges are formally framed. The accused must then plead guilty or not guilty.

The Trial: If the plea is "not guilty," the trial begins. The prosecution has to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, presenting evidence and calling witnesses. The defence gets to cross-examine those witnesses and present its own side of the story.

The Finish Line: Judgment: After all the evidence is in and both sides have made their final arguments, the Magistrate delivers the judgment—either convicting or acquitting the accused.

This entire process can be long and incredibly document-heavy. For any lawyer, ensuring every piece of paper—from the initial complaint and bail applications to the final arguments—is perfectly drafted is non-negotiable.

This is where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. By generating sharp, accurate first drafts of documents like complaints or bail applications, lawyers can make sure all the procedural nuances of Section 448 IPC are hit correctly from the very start. It’s not just about saving time; it's about building a stronger, more coherent case from the ground up.

Distinguishing House-Trespass from Similar Offences

The Indian Penal Code has a whole web of property-related offences, and honestly, they can look confusingly similar at first. But for any lawyer handling a case under Section 448 IPC, knowing the fine lines that separate it from other types of trespass isn't just an academic exercise. It's a practical necessity for building a solid case.

If you get the charge wrong, the entire case can be thrown out before it even gets going. This is because the law sees different kinds of trespass with varying levels of seriousness. The core differences usually boil down to just three things: where it happened, the accused's intent, and whether they came prepared to cause harm. Getting this right is absolutely crucial.

Section 447 vs Section 448

The most common mix-up is between general criminal trespass and house-trespass. It's a simple distinction, but one that changes everything.

Section 447 IPC (Criminal Trespass): Think of this as the base-level offence. It covers unlawfully entering any kind of property with criminal intent—whether it's an open field, a factory floor, or a construction site. The punishment is lighter because the violation isn't as personal.

Section 448 IPC (House-Trespass): This is an aggravated, more serious version of criminal trespass. The law ramps up the seriousness because the act takes place in a space our society considers sacred and private: someone's home, a place of worship, or even a securely locked godown. The violation of a person's private dwelling is seen as a much graver breach of peace and security.

Basically, every act of house-trespass under Section 448 is also a criminal trespass, but not every criminal trespass is house-trespass. The location is the dealbreaker.

This flowchart gives you a bird's-eye view of the typical journey a Section 448 case takes, from the initial complaint right through to the question of bail.

As the visual shows, arrest and bail are critical early stages that can set the tone for the entire case.

The Escalation to Section 452

Things get even more serious when a trespasser shows up ready for a fight.

Section 452 IPC (House-trespass after preparation for hurt, assault or wrongful restraint): This is a much heavier charge. It kicks in when someone not only commits house-trespass but has also made clear preparations to injure someone, assault them, or wrongfully confine them. This preparation shows a premeditated criminal mind, and the punishment jumps significantly to a possible seven years in prison.

The key difference here is preparation. Someone who barges into a home to have a shouting match is one thing. But someone who enters carrying a weapon, a rope, or anything that shows they planned to cause harm? That demonstrates a pre-planned intent to escalate, triggering the much tougher charge under Section 452.

InsightsNailing the specific offence is the very first move in your legal playbook. Charging someone under Section 448 when the facts scream Section 452 can hobble the prosecution's case. On the flip side, an over-the-top charge that isn't backed by evidence can be easily dismantled by a sharp defence lawyer.

Section 448 IPC vs Other Trespass Offences

To make these distinctions crystal clear, let's break them down side-by-side.

Offence (IPC Section) | Core Element | Place of Offence | Punishment Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

Criminal Trespass (S. 447) | Unlawful entry with criminal intent. | Any property (land, building, etc.). | Low (Up to 3 months) |

House-Trespass (S. 448) | Unlawful entry into a dwelling or place of worship/custody. | A human dwelling or specific protected place. | Medium (Up to 1 year) |

House-trespass with preparation for hurt (S. 452) | House-trespass plus active preparation to cause harm. | A human dwelling or specific protected place. | High (Up to 7 years) |

As you can see, the law creates a ladder of severity. It all starts with simple trespass, but the moment the offence moves into a private dwelling, the stakes get higher. And when preparation to cause harm is involved, the law comes down much harder.

It's worth noting how Section 448 IPC is increasingly used in urban property disputes. In cities like Mumbai and Bengaluru, for example, it's been found that over 35% of property-related criminal complaints involved house-trespass allegations, often weaponised by landlords against tenants who overstay their lease. This shows how a criminal provision can bleed into what are, at their core, civil disagreements. For a deeper dive, check out the research from the Centre for Civil Society.

Navigating these subtle but critical differences requires a careful eye for the facts. This is where modern tools can give you an edge. A Legal AI called Draft Bot Pro can help a lawyer structure the initial complaint or notice perfectly. The AI can prompt you to detail the specific location, the nature of the intent, and any evidence of preparation, making sure the document you draft aligns with the correct legal provision right from the get-go.

Strategic Insights for Defending a Section 448 Charge

Successfully defending against a Section 448 IPC charge isn't about grand courtroom drama. It’s about a sharp, focused legal strategy that meticulously dismantles the prosecution's case, element by element. More often than not, the battle is won by showing the prosecution has simply failed to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

This means poking holes in their narrative, challenging the evidence of criminal intent, and presenting a logical, alternative reason for why the accused was on the property. A solid defence is built on a deep understanding of the common arguments that have already passed muster with the courts.

Common Defences Against House-Trespass

When you're up against a Section 448 allegation, the defence usually boils down to a few core arguments. The real goal is to dismantle the essential ingredients of the offence, especially that all-important element of a guilty mind, or mens rea.

Here are some of the most effective lines of defence you’ll see in practice:

No Criminal Intent: This is the bedrock of nearly every defence strategy. The argument is simple: while the accused might have entered the property, they had no intention to commit an offence, or to intimidate, insult, or annoy anyone. Think of someone entering a relative's house during a heated property dispute to talk things over—their intent was to find a resolution, not to threaten anyone.

Claim of Right: An accused person can argue they had a bona fide (good faith) belief that they had a legal right to be there. This could be a tenant who genuinely thinks their lease is still active or a co-owner who isn't aware of a partition. If the court believes the claim is genuine and not just a flimsy excuse, it can completely negate the criminal intent needed for a Section 448 IPC conviction.

Consent from the Owner: A straightforward defence is that the entry wasn't unlawful because the owner or the person in possession gave their permission. This could be express consent, like a verbal invitation, or implied consent, like a long history of being allowed to enter freely. The burden then shifts to the prosecution to prove that consent was either withdrawn or never valid in the first place.

InsightsCourts are very wary of letting Section 448 IPC be used as a weapon to settle civil disputes. If a case looks more like a property or family squabble dressed up as a criminal complaint, judges will scrutinise the evidence of criminal intent much more closely and may well tell the parties to take their fight to a civil court where it belongs.

Landmark Judgments and Judicial Interpretation

The way higher courts have interpreted Section 448 gives us a powerful toolkit for building a defence. Over the years, the Supreme Court and various High Courts have laid down crucial principles that clarify just how far this provision can reach.

Judges consistently stress that just walking onto a property isn't enough. The prosecution has to prove a specific, dominant intent. For example, in several key rulings, courts have held that the "intent to annoy" must be the main reason for the entry, not just an accidental side-effect. If annoyance is just a byproduct of entering for another legitimate purpose (like getting your own things back), a conviction probably won't hold up. These precedents are gold when you're arguing against a charge.

The sheer volume of these cases, especially in property conflicts, is clear from official data. NCRB figures for 2021 show that a staggering 1,14,327 cases were registered under the broader 'Criminal Trespass' category. Section 448 makes up a huge chunk of this, particularly in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. You can dig into these statistics yourself on the National Crime Records Bureau website.

How Draft Bot Pro Fortifies Your Defence Strategy

Building a tough defence requires meticulous preparation and rock-solid paperwork. This is where a Legal AI called Draft Bot Pro becomes a critical ally for any legal professional.

Take drafting a bail application, for instance. You have to frame your arguments just right. For a Section 448 IPC charge, you might be seeking anticipatory bail if an arrest seems likely. Draft Bot Pro can help structure the application by immediately highlighting the bailable nature of the offence and framing arguments that attack the idea of criminal intent from the get-go. To see how this works, check out our detailed guide to anticipatory bail under Section 438 CrPC.

The AI can also rapidly research relevant case law and find precedents where courts have quashed similar charges. This gives you the judicial backing you need to strengthen your arguments and effectively challenge whatever the prosecution throws at you.

How Legal AI Can Sharpen Your Section 448 Case Preparation

In today's legal practice, it’s not just about working hard; it's about working smart. Speed and precision aren't just nice-to-haves—they're essential. For lawyers handling cases under Section 448 IPC, technology provides a powerful edge, helping you manage your workload and build stronger cases right from the get-go.

Think of Legal AI tools like your dedicated paralegal, one that handles the tedious, time-consuming parts of the job. This frees you up to focus on what truly matters: case strategy, client relationships, and courtroom performance. Imagine shrinking hours of initial drafting and research down to a matter of minutes. That’s the real-world advantage a tool like Draft Bot Pro delivers.

Get Your First Drafts Done in a Flash

One of the most immediate payoffs is the ability to generate the first drafts of crucial legal documents almost instantly. A lawyer can whip up a properly structured criminal complaint or a detailed bail application that hits all the essential ingredients of a Section 448 IPC offence.

For instance, when you're drafting a complaint, the AI makes sure your document clearly lays out:

The unauthorised entry into a person's home (actus reus).

The specific criminal intent—to annoy, intimidate, or commit another offence (mens rea).

The specific facts that elevate it from a simple civil tiff to a criminal matter.

Having this solid foundation ensures you don't miss a critical legal point, setting you up for success down the line.

InsightsA well-crafted initial document really sets the tone for the entire case. Using an AI assistant helps maintain consistency and accuracy from the FIR or complaint stage, which can be a game-changer when you get to charge framing and the trial itself.

Supercharge Your Legal Research

Beyond just drafting, Legal AI completely changes the research game. Forget spending hours manually sifting through case law databases for the right precedent. Now, you can simply ask the AI to pull up relevant cases related to house-trespass.

A Legal AI like Draft Bot Pro, for example, can instantly find Supreme Court and High Court judgments that dig into the nuances of what "intent to annoy" really means, or what legally qualifies as a "dwelling" under Section 448. The best part? Every piece of research is backed by a verifiable source, so you can quickly find and cite compelling authorities to bolster your arguments. You can get a closer look at how this works by reading about AI for trial preparation on our blog.

This is a massive help when you're preparing for a bail hearing. You can ask the AI to find cases where bail was granted in similar Section 448 IPC matters, giving you ready-made arguments to present in court. For a wider view of what’s out there, checking out resources on the best AI tools for lawyers can provide more context. At its core, Legal AI acts as a force multiplier, helping you build stronger, better-researched cases in a fraction of the time.

Your Top Questions on Section 448 IPC Answered

To round out our deep dive into house-trespass, let's tackle some of the most common questions I hear about Section 448 IPC. Think of this as a quick-fire round to lock in your understanding.

Is an Offence Under Section 448 IPC Bailable?

Yes, absolutely. An offence under Section 448 of the Indian Penal Code is bailable. This is a crucial procedural detail. It means an accused person has a right to be released on bail, either straight from the police station or by the court, once they furnish a security bond.

Unlike non-bailable offences where getting bail is up to the judge's discretion, here it’s a matter of right. This makes a huge difference in the initial stages of a case, giving the accused a clear pathway to release while they await trial.

Can a Landlord Use Section 448 Against a Tenant?

A landlord can certainly file a case, but actually getting a conviction is another story. The real challenge is proving the tenant had a criminal intent—meaning, they stayed specifically to annoy, intimidate, or insult the landlord. Most of the time, it just looks like a civil dispute over possession.

Courts are very wary of letting landlords use criminal law as a back-door eviction strategy, which is meant to be handled by civil rent control laws. A Section 448 IPC case only gains traction if the tenant does more than just overstay. We're talking clear acts of intimidation, threats, or causing a nuisance.

InsightsThe line between a civil tiff and a criminal act is everything in landlord-tenant cases under Section 448. The prosecution has to bring solid evidence showing the tenant's main goal was criminal, not simply a refusal to hand over the keys.

What's the Main Difference Between Section 447 and 448?

It all comes down to where the trespass happened.

Section 447 IPC covers criminal trespass on any kind of property. This could be an open plot of land, an office space, or a shop. It's the general, catch-all provision.

Section 448 IPC is more serious. It specifically deals with 'house-trespass'—entering a building, tent, or vessel that's used as a home, a place of worship, or for storing property.

The law sees someone invading your home as a much graver violation of your privacy and safety. That's why it gets its own, tougher section. The nature of the property is the bright line that separates the two.

How Can AI Help with a Section 448 IPC Case?

Legal AI assistants are genuinely becoming a game-changer for lawyers handling a Section 448 IPC case. Take a Legal AI called Draft Bot Pro, for example. It can whip up a solid first draft of a criminal complaint or a bail application in just a few minutes.

The real advantage is that the AI ensures you've pleaded all the essential ingredients of the offence, especially that tricky element of criminal intent. It can also pull up relevant case law and precedents on house-trespass almost instantly, helping you build a much stronger, evidence-backed argument for your hearings. It’s a massive time-saver and seriously levels up your case preparation.

Are you a legal professional looking to build stronger cases in less time? Draft Bot Pro is your go-to solution for expert AI-powered legal drafting and research. Join over 46,000 Indian lawyers and law students who trust our platform to create precise legal documents and find verifiable case law instantly. Discover a smarter way to practice law at https://www.draftbotpro.com.