Meaning of matrimonial home: A Clear Legal Guide

- Rare Labs

- Dec 21, 2025

- 17 min read

When you hear the term ‘matrimonial home’, it’s easy to think it’s all about who owns the property. Whose name is on the title deed? But in Indian law, especially when things turn sour in a marriage, the concept goes much deeper than that. It’s less about ownership and more about the fundamental right to reside.

This right is the cornerstone of protection offered under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA). The law’s main goal is to ensure a spouse, usually the wife, isn’t thrown out onto the street, regardless of who technically owns the house.

What Is a Matrimonial Home in Indian Law?

Legally speaking, there isn't a single statute that neatly defines "matrimonial home." Instead, its meaning is pieced together from various laws and landmark court judgments. At its very core, though, is the powerful legal term: the ‘shared household’. This is where the magic happens.

The crucial question the law asks isn't, "Who bought this property?" but rather, "Where did this couple build a life together in a domestic relationship?" This shift in focus is a game-changer. It prioritises a person's right to shelter over the technicalities of property ownership, especially during heated disputes.

Key Aspects Defining the Matrimonial Home

To really get to grips with this, you have to look beyond the sale deed. The law recognises that a home is more than just bricks and mortar; it’s the heart of a domestic relationship.

Here are the essential ingredients that make a property a ‘shared household’:

A Domestic Relationship: This is the bedrock. The parties must have lived together in a relationship resembling a marriage.

Shared Living Space: It must be a place where the couple has actually lived together, whether it was for a short time or for years.

Ownership is Irrelevant: This is the big one. The right to live there isn't tied to who owns the property. It could be owned by the husband, be a rented flat, or even belong to his parents or other relatives.

Insights: The law deliberately separates the right to live in the home from property ownership. Why? To counteract a common and cruel form of domestic abuse: threatening a woman with homelessness to control or intimidate her. This protective shield is one of the most vital aspects of the PWDVA.

To understand the practical difference, let's break down the common perception versus the legal reality defined by the PWDVA.

Matrimonial Home vs Shared Household Key Differences

This table offers a quick comparison to clarify how the law views the concept, moving beyond everyday assumptions.

Concept | Common Perception | Legal Reality (Under PWDVA) | Primary Right Conferred |

|---|---|---|---|

Definition | The house owned by the husband where the couple lives after marriage. | Any house where the couple has lived together in a domestic relationship. | Right to Residence |

Ownership | Tied directly to the husband's or joint ownership. | Ownership is not a determining factor. Can be owned, rented, or belong to relatives. | Protection from Dispossession |

Scope | Often seen as a single, primary family residence. | Can include multiple properties where the couple has resided together. | Right to Secure Shelter |

Legal Basis | A social and traditional concept. | A specific legal term defined under Section 2(s) of the PWDVA, 2005. | Legal Remedy Against Eviction |

As you can see, the legal definition of a ‘shared household’ is far more expansive and protective than the general idea of a ‘matrimonial home’. It's a purposefully broad definition designed to provide real-world security.

Streamlining Your Understanding with Legal AI

For any lawyer or law student navigating these waters, getting the details right is non-negotiable. When you're drafting a petition or a legal notice, you must precisely establish the existence of a shared household.

This is where specialised legal AI tools like Draft Bot Pro can be a massive help. You can input the case facts—like how long the couple lived together and the nature of the property—and the AI can help you frame the exact legal language needed to assert the right to residence. It ensures you don't miss a critical element in your initial pleadings, saving you time and strengthening your argument from day one.

The Legal Bedrock: Shared Household Under The PWDVA

To really get to grips with what a matrimonial home means in India today, you have to look past old-fashioned ideas and go straight to the law. The most powerful legal concept isn't 'matrimonial home' at all; it's the idea of a 'shared household', found in the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA).

This concept, defined right in Section 2(s) of the PWDVA, is the legal foundation for a woman's right to live in her home. It was deliberately made broad and expansive. Why? To stop technical arguments about property ownership from being used to throw a woman out on the street. The law cares about the relationship and the fact they lived together, not whose name is on the title deed. This was a game-changing shift.

Decoding Section 2(s): What Is a Shared Household?

The law itself paints the clearest picture. A 'shared household' is where the aggrieved person lives or has lived at any point in a domestic relationship. This relationship is usually with her husband or his family, and it covers houses that are owned, rented, or even places where neither of them has any legal title.

Let’s break down the most important parts:

"Lives or at any stage has lived": This bit is absolutely critical. It means a woman doesn't lose her right to live in the home just because she was forced out by abuse. If she lived there before, it’s still legally her shared household.

"In a domestic relationship": This sets up the connection. It covers people who live together (or have in the past) and are connected by marriage, blood, or adoption.

"Whether owned or tenanted... or a joint family house": This wording explicitly severs the link between ownership and the right to stay. It confirms the home could be rented, belong to the in-laws, or be part of a larger Hindu Undivided Family (HUF) property.

This wide-ranging definition makes sure the law's protective shield is as big as possible, stopping abusers from weaponising property titles.

The Judiciary’s Protective Stance

Indian courts have consistently backed this broad interpretation. Time and again, landmark judgments have prioritised a woman's fundamental right to shelter over claims of property ownership. The courts know that if they interpreted this definition narrowly, the whole point of the PWDVA would be lost. They look at the reality of how people were living, not just the legal paperwork.

For instance, the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that a wife can't be kicked out of a shared household even if it's owned solely by her in-laws, as long as she lived there with her husband. This puts a stop to the common tactic where a husband claims he owns nothing in his name to deny his wife a roof over her head. The courts get it: the essence of a shared household is the shared life lived inside it.

Insights: The legal framework around the shared household is all about providing immediate, real-world relief. The goal isn't to decide who owns the property; it's to prevent a woman from being made homeless. This is exactly why interim orders, which can be granted very quickly, are so crucial in these cases.

How Draft Bot Pro Helps You Make Your Case

Navigating the PWDVA and proving the existence of a 'shared household' demands sharp, precise legal drafting. This is where a legal AI tool gives you a real edge. Draft Bot Pro can help you articulate these points with total clarity.

You can input the facts of your case—how long they lived together, the nature of the property—and the AI helps generate pleadings that frame the argument perfectly, citing the law right from the start. This ensures your client's claim to the meaning of matrimonial home as a shared household is presented in the strongest possible way.

For a deeper dive into the types of court orders you can get, check out our detailed guide on Section 19 of the Domestic Violence Act, which deals specifically with residence orders.

Distinguishing Ownership From The Right To Reside

One of the biggest hurdles in any matrimonial dispute is clearing up the confusion between owning the house and having the right to live in it. It's a deeply ingrained myth that marriage, or years of homemaking, automatically gives a spouse an ownership slice of the property pie. Under Indian law, this just isn't true.

The right to reside in a shared household is a personal right, a shield created by the PWDVA to prevent a spouse from being thrown out onto the street. It’s about immediate security. Ownership, on the other hand, is a completely different ball game. Proving a proprietary interest is a long-drawn battle fought in a civil court, with its own set of rules and evidence.

This isn't just a technicality; it shapes the entire legal strategy. It dictates how you frame your case and, crucially, how you manage your client's expectations from day one. The right to residence is a protective measure, not a backdoor to claiming ownership.

Ownership Scenarios And The Right To Reside

Let's break this down with a few real-world scenarios. You'll notice that the wife's right to live in the home remains rock-solid in these situations, even when she has zero claim to ownership.

Home Owned by the Husband: This is the most straightforward case. If the husband is the sole owner, establishing the wife's right to reside in the property as a shared household is usually a simple task.

Home Owned by In-laws: A wife absolutely has a right to live in a house owned by her in-laws, provided she lived there with her husband as part of their domestic life. Courts have consistently held that in-laws can't just evict her because her name isn't on the title deed.

Joint Family Property: The same principle applies if the couple lived in a property belonging to a Hindu Undivided Family (HUF). It qualifies as a shared household, and the wife can't be kicked out.

Rented Accommodation: Even rented apartments are covered. A husband can't try to get his wife evicted by simply refusing to pay the rent. In fact, courts can step in and order him to keep paying or arrange for a suitable alternative place for her to live.

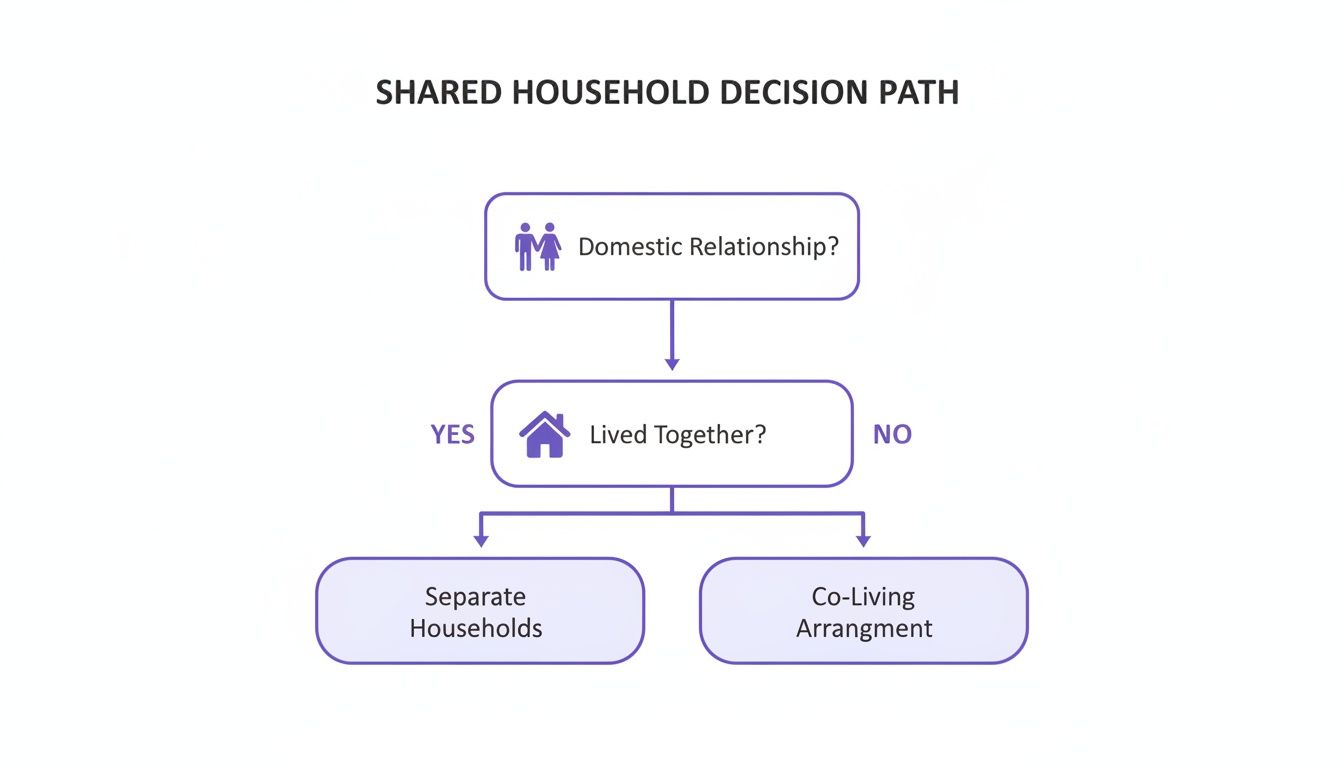

This flowchart boils down the key questions a court asks when figuring out if a property is a shared household.

As you can see, the test is all about whether a domestic relationship existed and if they lived there together. It deliberately sidesteps the messy, time-consuming question of who actually owns the property.

The Legal Framework And Non-Monetary Contributions

A major point of contention, and heartache for many clients, is the value of non-monetary contributions. India’s property laws are clear: the immense, often thankless, work of a homemaker doesn't magically translate into an ownership share of the home. Courts are thankfully starting to recognise these contributions when calculating maintenance and alimony, but it still doesn't create a title interest in the property itself.

Insights: There’s a very practical reason the law separates residence rights from ownership. It allows courts to pass quick, interim orders to protect a vulnerable spouse from being made homeless. If the court first had to untangle complex ownership claims—a process that can take years—the entire protective purpose of the PWDVA would be lost.

This legal setup exposes a real challenge. Since there’s no single law defining "matrimonial home," we borrow the "shared household" concept from domestic violence law to secure residence rights. Yet, our family and property laws don't automatically grant ownership just because you lived there as a married couple. It's a significant gap, especially when you consider that an estimated 67%–70% of Indian women perform unpaid domestic work, contributions that often count for nothing in an ownership dispute. You can discover more insights about the rights of women in matrimonial laws on Lawyered.in.

Clarifying Legal Strategy With AI

As a lawyer, explaining this distinction to a distressed client is one of your most important jobs. It’s a delicate conversation that requires managing both emotions and expectations. This is where a tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. When you're putting together that initial petition, the AI helps you laser-focus the language on proving the "shared household" criteria to secure those crucial residence orders.

You can feed it the facts of your case, and Draft Bot Pro will help generate pleadings that correctly frame the relief you're seeking—protection from dispossession—without getting sidetracked by premature and complicated ownership claims. This kind of precision makes your legal strategy tighter, more focused, and perfectly aligned with the immediate protective remedies the law actually provides.

How Landmark Judgments Shaped The Law

The legal idea of a matrimonial home in India isn't something set in stone; it's a living concept, shaped and chiselled over time by the judiciary. While the PWDVA gives us the black-and-white text, it's the courts that have truly breathed life into those words, creating a powerful story of how women's rights have evolved through landmark judgments. These rulings aren't just case names to be cited; they are the very foundation of modern legal strategy in this field.

For years, the law grappled with a tough, all-too-common question: what happens when the home a couple lives in is legally owned by the husband's parents or relatives? This was the heart of the matter in the famous case of S. R. Batra & Anr vs. Smt. Taruna Batra (2007). In that instance, the Supreme Court initially took a very narrow view. It suggested that a 'shared household' had to be a property the husband either owned outright or at least had a share in.

This decision sent shockwaves through the legal community and left countless women in a lurch. It meant that if a woman lived in a home registered in her in-laws' names—a deeply common practice in India—she could be left with no legal remedy to stay there. This created a massive loophole, one that could be easily used to push a wife out of her home.

Correcting The Course After Batra

Thankfully, the story didn't end there. Recognising the profound injustice this created, the judiciary began a crucial course correction. The legal community and subsequent court rulings started pointing out that the Batra decision actually went against the very soul of the PWDVA, which was always meant to offer the broadest possible protection to women.

The real turning point arrived with the Supreme Court's verdict in Satish Chander Ahuja vs. Sneha Ahuja (2020). This judgment was a game-changer. It directly overruled the restrictive interpretation from Batra and brought back the wide, protective meaning of a 'shared household'.

Insights: The evolution from Batra to Ahuja is a perfect example of how the judiciary can self-correct to uphold the spirit of the law. The Ahuja judgment reinforced that the PWDVA is social-welfare legislation, meaning its provisions must be interpreted liberally to achieve its protective purpose, rather than being read like a rigid property statute.

This ruling made it crystal clear: a wife's right to live in a shared household doesn't hinge on whether her husband owns the property. If she lived there as part of a domestic relationship, it is her shared household. Full stop.

Key Legal Precedents and Their Impact

The journey from the Batra case to the Ahuja case is a perfect example of how case law isn't static—it evolves. Each of these major cases gives lawyers a powerful precedent to build their arguments on. Let's break down what you should be looking for:

Facts of the Case: You have to get into the weeds of the living arrangements and who owned what. The details matter.

Legal Question: What was the core issue the court had to decide? For example, "Does a wife have a right of residence in a house owned exclusively by her mother-in-law?"

Court's Reasoning: This is the gold. Understanding why the court ruled a certain way gives you the logic to frame your own arguments.

Lasting Implications: How did the judgment change the game? The shift from Batra to Ahuja completely flipped the script on how lawyers approach these residence claims.

For any legal professional practicing in this area, keeping up with these precedents isn't just a good idea; it's absolutely non-negotiable. Your client's entire case can stand or fall based on citing the most current and relevant authority.

Using Legal AI to Navigate Case Law

The body of case law around the meaning of matrimonial home is huge, and it's always growing. Trying to manually track every development, analyse it, and then apply it perfectly to your client's unique situation is a massive, time-consuming effort that leaves no room for error.

This is where a tool like Draft Bot Pro becomes a real ally for the modern lawyer. Imagine you're drafting a petition. You can input the specific facts of your client's case, and the AI can instantly help you pinpoint and weave in the most potent judicial observations from rulings like Satish Chander Ahuja. It makes sure your pleadings aren't just factually sound but are also backed by the strongest and latest legal precedents, right from the very first draft. It helps you construct arguments that are firmly rooted in the current interpretation of the law, giving your client's case the solid legal foundation it needs to succeed.

Enforcing Your Right to Reside with Legal Remedies

Knowing you have a right to live in your matrimonial home is one thing. Actually enforcing it when that right is threatened is another ball game entirely. Thankfully, the law isn't a silent spectator. It provides a powerful toolkit, primarily through the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (PWDVA), built for swift and decisive action against dispossession.

This isn't about getting bogged down in property title disputes that can drag on for decades. The remedies under the PWDVA are designed for immediate relief. The goal is simple: to make sure a vulnerable person isn't tossed out onto the street while other legal battles unfold. It’s about securing a roof over your head, right now.

The Power of Interim Orders

When someone is facing the very real threat of being thrown out of their home, they can't afford to wait months or years for a final judgment. This is where the PWDVA truly shines. It gives Magistrates the power to grant interim orders – a form of urgent, temporary relief that protects the aggrieved person while the case is still being heard.

This is arguably the most critical feature of the entire Act. An interim residence order can be passed incredibly quickly, sometimes at the very first hearing, based on a first-look assessment of the facts. This immediate shield prevents an abuser from creating a 'fact on the ground' by making the victim homeless, which would make their legal fight infinitely harder.

Insights: The speed and accessibility of interim orders are the PWDVA's greatest strengths. The whole point of the law is to provide a rapid response to a crisis at home. This is precisely why a well-drafted initial application is everything; it has to lay out the grounds for immediate court intervention in a way that is clear, concise, and compelling.

Key Legal Remedies Under the PWDVA

The PWDVA provides a menu of specific orders that can be requested to protect the right to reside in the matrimonial home. As a lawyer, you'll typically ask for a combination of these reliefs to create a comprehensive safety net for your client.

1. Residence Orders (Section 19)This is the big one. It's the cornerstone of protection. A court can pass an order that:

Stops the other party from dispossessing the aggrieved person or disturbing their peace in the shared household.

Directs the other party to actually remove themselves from the shared household.

Restrains the other party (or their relatives) from even entering any part of the shared household where the aggrieved person is living.

2. Protection Orders (Section 18)While these orders are broader, they are vital for ensuring you can live peacefully. A protection order can prohibit the respondent from committing any act of domestic violence, which includes actions that would make living in the home unbearable.

3. Monetary Reliefs (Section 20)The court can also step in financially. It can order the respondent to pay for expenses or losses the aggrieved person has suffered. This can mean directing them to keep paying the rent on a rented home or even to secure and pay for a suitable alternative place to live if the situation demands it.

The Application Process and Evidence

To get these orders, a formal application has to be filed before the Magistrate. This application, usually supported by a personal affidavit, must clearly establish a few non-negotiable points:

The existence of a domestic relationship between the two parties.

The fact that the house in question is indeed a shared household.

Specific details of the domestic violence or the direct threats of being thrown out.

Evidence is king here. This can include photos, statements from witnesses, copies of police complaints, or even WhatsApp messages that show the threat of eviction. Your job is to paint a clear picture for the court that screams "urgent intervention needed!"

Leveraging AI for Precision Drafting

When you're drafting an application for urgent interim relief, every second counts, and every word matters. Each prayer needs to be perfectly formulated, and every essential fact must be included to convince the court of the urgency. This is where a legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro becomes a massive advantage.

As a legal professional, you can input the specific facts of your case—the nature of the relationship, a description of the shared household, the details of the threats. Draft Bot Pro can then generate a precise and thorough draft application for interim reliefs. It makes sure that crucial prayers, like restraining dispossession or preventing the sale of the property, are worded correctly from the get-go. This dramatically improves the odds of securing that vital, immediate protection for your client.

Drafting Effective Pleadings With AI Assistance

When you’re fighting for a client’s right to stay in her home, the battle is often won or lost at the very first step: the pleading. A well-drafted petition isn’t just a formality. It’s the strategic foundation for every single order you hope to get, especially those urgent, game-changing interim reliefs.

A weak or incomplete pleading can stall a strong case, introduce fatal delays, or even get it dismissed. It's a high-stakes document where you have to perfectly blend your client's story with the rigid legal framework of the PWDVA. Getting this right is meticulous work, and the pressure is immense, especially for junior advocates or those juggling a heavy caseload.

An Essential Checklist For Your Pleadings

Think of your petition as building a case brick by brick. Each point must logically connect to the next, creating an undeniable argument that compels the court to intervene and protect your client’s right to reside in her shared household.

Here's a checklist of the absolute must-haves:

Establish the Domestic Relationship: Don't just mention it; clearly state the nature and length of the relationship. Make it crystal clear that it fits the definition under the PWDVA.

Identify the Shared Household: Give a precise address and description of the property. Crucially, detail the period your client lived there to firmly establish it as her shared household.

Detail Acts of Domestic Violence: List the specific acts of violence—physical, emotional, economic—systematically. You have to draw a direct line connecting these abusive acts to the threat of her being thrown out.

Frame Specific Reliefs: Your prayer clause needs to be sharp and specific. Don’t just ask for “protection.” Ask for a residence order under Section 19, a protection order under Section 18, and any monetary reliefs needed.

Insights: The structure of your pleading is crucial. Start with the relationship, establish the shared household, detail the abuse, and then conclude with specific, actionable prayers. This logical flow makes it easy for the court to grasp the urgency and the legal basis for granting immediate relief.

How AI Brings Precision and Efficiency to Drafting

Using legal AI is no longer some futuristic idea; it’s a smart, practical move for any lawyer today. It acts as an expert assistant, ensuring your foundational documents are rock-solid from the get-go. A tool like Draft Bot Pro can take your client’s raw, factual story and instantly structure it into a legally sound pleading. You input the case background, and it generates a robust draft that hits all the right notes—correct legal terms, statutory provisions, and a well-formed prayer clause.

This kind of technological backup frees you up to focus on the bigger picture—case strategy, client counselling, and preparing for arguments—knowing your drafting foundation is solid. To see how this works in practice, you can explore our detailed guide on how to use AI for drafting legal documents. It’s all about making sure your pleadings are not just complete, but strategically powerful.

Answering The Tough Questions About The Matrimonial Home

Even with a solid grasp of the law, the real world throws up some tricky situations when it comes to the meaning of a matrimonial home. Let's tackle some of the most common questions that lawyers and their clients grapple with.

Can A Woman Claim Residence In Her Mother-in-law's House?

Yes, absolutely. This is a classic scenario. If the house is where she lived with her husband as a couple—making it a ‘shared household’ under the law—her right to live there is protected.

The Supreme Court has been very clear on this time and again. It's not about whose name is on the property deed; what truly matters is the fact that it was the couple's shared home.

What If The Matrimonial Home Is A Rented Place?

A wife's right to reside in a shared household isn't limited to owned property; it covers rented accommodation too. A husband can't just pull the rug out from under his wife by suddenly deciding to stop paying the rent to get her thrown out.

Courts have the power to step in and order him to keep paying the rent. They can also direct him to find and pay for a similar alternative place for her to live.

Insights: The key in rented accommodation cases is to seek an immediate court order directing the husband to continue rent payments. This falls under monetary relief (Section 20 of PWDVA) and is crucial for preventing eviction by the landlord, which is often a backdoor tactic used by abusers.

Is The Right To Residence Absolute?

While it’s a powerful right, it isn't set in stone. The main goal of this legal protection is to prevent a woman from being made homeless overnight. It’s a shield against summary eviction.

However, a court will always try to balance the rights of everyone involved. If the situation calls for it, a judge can order the husband to provide a suitable alternative accommodation instead of allowing the wife to remain in that specific property. An AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can help you frame these arguments perfectly, whether the home is owned by in-laws, is a rented flat, or requires a claim for alternative accommodation.

When you're dealing with these complex family law matters, every word in your draft counts. Draft Bot Pro is an AI legal assistant built specifically for Indian lawyers. It helps you craft precise, well-structured legal documents in a fraction of the time. Get the expert assistance you need by visiting https://www.draftbotpro.com.