A Complete Guide to Section 148 IPC

- Rare Labs

- Nov 18, 2025

- 17 min read

Section 148 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) gets very specific: it deals with the serious offence of rioting while armed with a deadly weapon. This isn't just about a heated argument turning physical; it's a significant step up from a simple riot. The law creates this separate, more severe offence because the presence of deadly weapons completely changes the dynamic, elevating the potential for real harm.

Unpacking the Core Concept of Section 148 IPC

At its heart, Section 148 IPC is designed to tackle those situations where public order isn't just disturbed, but is actively threatened by a group that's not only violent but lethally equipped. Think about the difference between a spontaneous street brawl involving fists and shoves, versus an organised mob brandishing swords, firearms, or even heavy lathis. The law sees that difference clearly, and penalises the latter far more harshly.

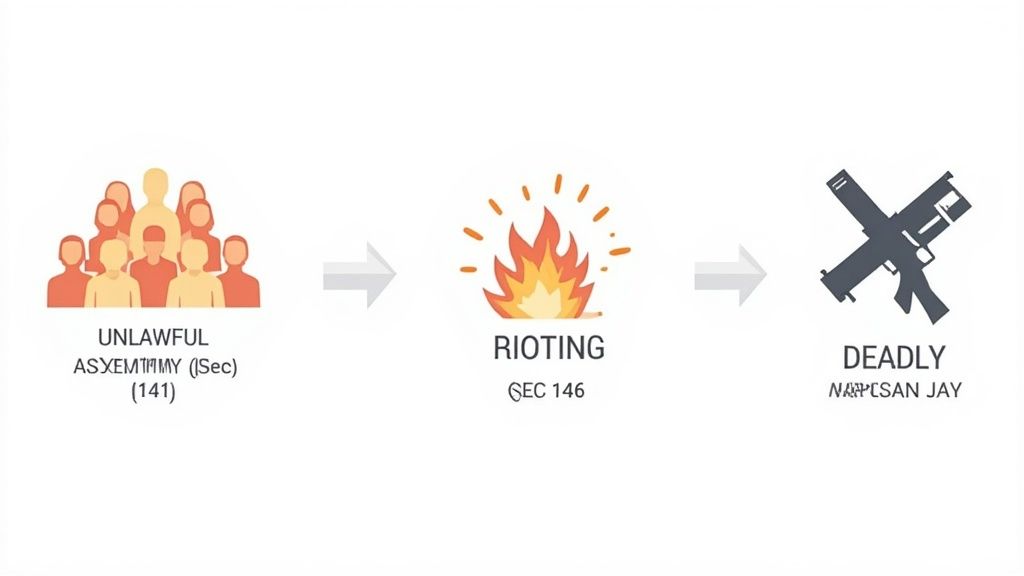

For the prosecution to make a Section 148 charge stick, they need to prove a specific chain of events. It all starts with the formation of an "unlawful assembly" – that's a group of five or more people sharing a common illegal goal. When that assembly uses force or violence to achieve its goal, it becomes "rioting."

The final piece of the puzzle, the one that kicks the charge up to Section 148, is proving that members of this riot were armed with deadly weapons.

What Counts as a "Deadly Weapon"?

This is a crucial question, and the law is intentionally broad. A "deadly weapon" isn't just about guns and knives. The test is whether the object, when used as a weapon of offence, is likely to cause death.

This can easily include things like:

Agricultural tools like sickles (daraanti) or axes.

Heavy stones or metal rods.

Any object, really, that is wielded with lethal intent during the riot.

This provision has been a cornerstone for maintaining public order since the IPC was drafted back in 1860. Anyone found guilty under Section 148 faces imprisonment for up to three years, a fine, or both. This reflects just how seriously the law views the act of arming oneself during a riot. You can dig deeper into the specifics and history of the provision on legal resources like lawrato.com.

Section 148 IPC at a Glance

For any practising lawyer or law student, having the core components at your fingertips is essential. This table breaks down what the prosecution absolutely must establish to prove an offence under Section 148.

Component | Description |

|---|---|

Unlawful Assembly | A gathering of five or more persons with a common illegal object as defined under Section 141 IPC. |

Act of Rioting | The use of force or violence by the unlawful assembly in pursuit of their common object (Section 146 IPC). |

Armed with Deadly Weapon | One or more members of the assembly must be armed with a weapon likely to cause death when used offensively. |

Active Participation | The accused must be proven to be a member of that assembly and participating in the riot. |

Getting these distinctions right from the outset is the first step in building a solid case. A lawyer using a specialised legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can instantly pull up the bare text of Sections 141, 146, and 148 to compare the language side-by-side. This ensures every single ingredient is addressed in initial drafts, which can save hours of research time down the line.

The Building Blocks of a Section 148 Offence

To really get a handle on Section 148 IPC, you have to think of it like building with blocks. Each legal requirement is a block that needs to be perfectly placed on top of the last. Pull out even one of these blocks, and the whole charge comes tumbling down.

It’s not a single act but a specific sequence of events. We'll break down how a situation escalates from a simple gathering to the serious offence of rioting with a deadly weapon. For any lawyer or student tackling this, knowing these ingredients inside and out is non-negotiable.

Ingredient 1: The Foundation of an Unlawful Assembly

Everything starts here, with the concept of an unlawful assembly under Section 141 of the IPC. This is the absolute bedrock of any rioting charge. For an assembly to be "unlawful," it must have five or more people sharing a common, illegal goal.

The IPC is very specific about what counts as a "common object":

Using criminal force to scare the government or a public servant.

Resisting the execution of a law or legal process.

Committing an offence like mischief or criminal trespass.

Forcibly taking property or denying someone a right they're entitled to.

Forcing someone to do something they aren't legally required to do.

It’s a numbers game. If only four people gather, even with weapons and bad intentions, it’s not an unlawful assembly by this definition. That means a Section 148 charge is dead on arrival. The "five or more" rule is a hard line.

Ingredient 2: The Escalation to Rioting

The next block in the stack is the act of rioting. An unlawful assembly is a state of being; rioting is that assembly kicking into action. Section 146 IPC spells it out: when any member of an unlawful assembly uses force or violence to achieve that common goal, every single member is guilty of rioting.

Think about it this way: five people gather to stop a demolition crew. At that moment, they are an unlawful assembly. The second one of them shoves an official or lobs a stone, the entire group has committed the offence of rioting. It doesn't matter if the other four just stood there; they are all in it together.

Key Insight The switch from an unlawful assembly to a riot happens in an instant. The very first act of violence by anyone in the group, as long as it's aimed at their shared goal, triggers the change. That connection between the violence and the common object is crucial.

Ingredient 3: The Defining Element — A Deadly Weapon

This is the final, game-changing ingredient. It’s what separates a standard rioting charge under Section 147 from the much more serious offence under Section 148 IPC. At least one person in that rioting group must be armed with a deadly weapon or anything that, when used to attack, is likely to cause death.

But what's a "deadly weapon"? It’s a question of fact, not just a fixed list. We’re not only talking about guns and swords. Courts have recognised that heavy iron rods, sickles, axes, and even thick, heavy sticks (lathis) can qualify, depending on their size and how they're used. The real test isn't what the object is, but what it becomes in the hands of a person intending to cause harm.

For a legal professional, taking these elements apart is the most critical part of the job. You could use a tool like Draft Bot Pro to quickly create a memo that maps the facts from an FIR directly onto these legal ingredients. This helps ensure every block is accounted for, whether you're drafting a charge sheet or arguing for bail, and helps you spot the fatal flaws in the other side's case.

Comparing Section 148 With Related Offences

When you're in the trenches of criminal law, knowing the fine lines between similar offences isn't just a good idea—it's everything. Confuse Section 148 IPC with its close cousins, Sections 147 and 149, and you risk framing a weak charge or building a defence on shaky ground. Let's draw a clear line in the sand.

Getting these distinctions right is foundational. Each of these sections deals with group violence, but they target very different aspects of the crime, from the specific weapons involved to the very nature of who's held responsible. This clarity is what turns a decent legal argument into a winning one.

Section 148 vs. Section 147: Simple Rioting

The most straightforward comparison is with Section 147, the provision that punishes the basic act of rioting. The difference between a charge under Section 147 and Section 148 IPC boils down to one simple, yet game-changing detail: the presence of a deadly weapon.

Think of it this way: a group forms an unlawful assembly to protest, and things get heated. They start pushing barricades and shoving police. That’s a riot, plain and simple, and it falls squarely under Section 147, which carries a sentence of up to two years.

Now, change one fact. Imagine a few people in that same crowd are holding iron rods, hockey sticks, or anything else that could easily cause death. Suddenly, the entire situation is elevated. Every member of that riot can now be booked under Section 148. The potential punishment jumps to three years.

The key takeaway? The law sees the mere presence of a deadly weapon as a serious aggravating factor. It signals a readiness for lethal violence and poses a much greater threat to public order. This is why Section 148 IPC brings a harsher penalty, even if the weapon is never actually used.

Section 148 vs. Section 149: Constructive Liability

This is where the wires often get crossed. Section 149 isn’t a standalone crime like Section 148. It’s a rule of vicarious or constructive liability. In simple terms, it makes the whole group responsible for a crime committed by just one of its members, as long as it was done in pursuit of the group's "common object."

Let's break it down:

Section 148 is a specific offence: you rioted, and you (or someone in your group) were armed with a deadly weapon.

Section 149 is a legal principle: it pins the guilt for a separate crime committed by one person onto everyone in the unlawful assembly.

For instance, say an unlawful assembly forms with the common goal of intimidating a rival family. During the chaos, one member pulls out a bat and grievously injures someone. Thanks to Section 149, every single person in that assembly can be charged with causing grievous hurt, even if they never touched the victim. If you want a deeper dive into offences like this, our explainer on punishment under Section 325 IPC is a great resource.

It’s very common to see charges under both Sections 148 and 149 framed together. An accused might be charged under Section 148 IPC for being part of an armed riot and simultaneously charged under Section 149 for being vicariously liable for a more serious crime—like murder or assault—committed by another member during that same riot.

A Quick Comparison Table

To really hammer these differences home, let’s lay it all out in a simple table.

Section 148 vs Section 147 vs Section 149 IPC

Provision | Core Element | Weapon Requirement | Nature of Offence | Punishment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Section 147 IPC | Simple rioting by an unlawful assembly. | None. The use of any force or violence is sufficient. | Substantive offence | Up to 2 years imprisonment, or fine, or both. |

Section 148 IPC | Rioting while armed with a deadly weapon. | Mandatory. At least one member must be armed. | Substantive offence | Up to 3 years imprisonment, or fine, or both. |

Section 149 IPC | Vicarious liability of all members. | Dependent on the primary offence committed. | Rule of evidence/liability | Same as for the principal offence committed. |

For legal professionals, navigating these sections requires precision. A legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be invaluable here. By using its AI legal research feature, a lawyer can quickly find case law that differentiates between these sections based on specific factual scenarios, helping to build a more nuanced and effective argument in court.

Key Judicial Insights from Landmark Cases

Legal textbooks give you the black-and-white rules, but the courtroom is where the law comes alive. To really get a grip on Section 148 IPC, you have to dive into the landmark cases where the Supreme Court and various High Courts have drawn the line between a strong accusation and a solid conviction. These judgments are goldmines, showing how abstract legal ideas get applied to the messy reality of actual events.

For any practising lawyer, these precedents are the tools of the trade. They're what you use to argue what counts as a "deadly weapon" in a specific fight, or to poke holes in the prosecution's story about your client's involvement. If you want to build a winning argument, knowing this case law isn't just helpful—it's non-negotiable.

Active Participation vs. Just Being There

One of the most crucial lines the courts have drawn is this: simply being present at a riot isn't enough to get convicted under Section 148 IPC. The prosecution has to bring forward real evidence showing the accused was an active participant.

This is a massive distinction. It acts as a safeguard for people who might have just been bystanders, or were in the wrong place at the wrong time without sharing the unlawful assembly's illegal goal. Courts have said time and again that the onus is on the prosecution to prove the accused wasn't just in the crowd, but was an active part of the mob causing the trouble.

Judicial Insight "In order to convict a person under Section 148 of the Indian Penal Code, the evidence must clearly establish that he was not only a member of the unlawful assembly but was also armed with a deadly weapon."

This standard forces the prosecution to do its homework. They can't just make sweeping allegations; they have to connect each specific person to the assembly and its criminal acts.

The Judhisthir Pradhan vs State of Orissa Precedent

The case of Judhisthir Pradhan vs State of Orissa (1991) is a classic on this point. It’s a powerful reminder that suspicion, no matter how strong, can never take the place of cold, hard evidence. In that case, the court took a close look at the evidence and found it just wasn't strong enough to prove the accused were actively involved or armed as the law requires.

This judgment, and many others like it, have cemented the legal requirements. Over the years, a whole body of case law has made it clear that Section 148 IPC won’t apply if the accused wasn't armed with a dangerous weapon, didn't use any violence, or wasn't an active participant. Cases like Rameshwar vs State of U.P. (2002) and Kefrumog vs State of Tripura (2006) have hammered this home, establishing that you can't convict someone on mere presence or general suspicion alone. You can find more on the nuances of when these charges fail on Supreme Today.

These precedents are invaluable for a defence lawyer, giving you a solid legal foundation to fight back against charges built on shaky ground.

What Makes a Weapon "Deadly" in the Eyes of the Court?

The term "deadly weapon" is another area where judicial wisdom shines. Instead of a fixed, rigid list, courts have taken a very practical, context-based approach.

Here’s a breakdown of how a judge might think about it:

The Nature of the Object: Is it something that's inherently a weapon, like a knife or a firearm?

How It Was Used: Was a regular object, like a heavy stick or a rock, used in a way that it was likely to cause death?

The Injuries Inflicted: The type and seriousness of the injuries can be powerful evidence of the weapon's deadly potential.

This flexible approach means courtroom arguments often hinge on the specific facts of the incident. For lawyers and law students, this hammers home one point: you absolutely must do your case law research to find precedents that mirror the facts of your own case.

Using Legal AI for Smarter Case Law Research

Keeping up with decades of evolving case law is a huge task. This is where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. Forget spending hours manually digging through databases. You can use its AI-powered legal research features to find the exact judgments you need in seconds.

For example, you could ask for cases that specifically discuss whether a lathi is considered a "deadly weapon" under Section 148 IPC. The AI will instantly pull up the most relevant and recent rulings from various High Courts and the Supreme Court, complete with summaries and direct links. This kind of efficiency gives you a serious edge, helping you build stronger, more persuasive arguments in a fraction of the time.

Practical Insights for Legal Drafting

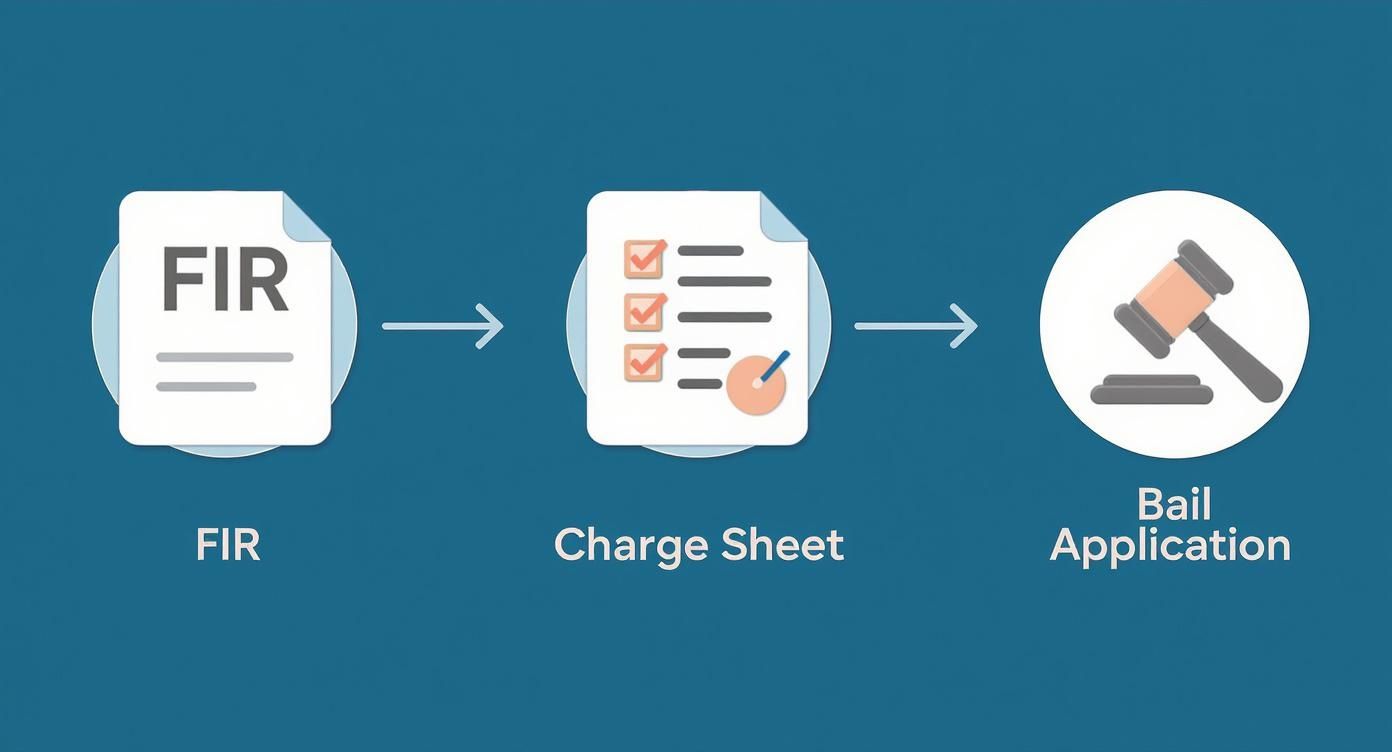

When a case under Section 148 IPC lands on your desk, the quality of your initial drafting can set the tone for the entire legal battle ahead. Whether you're framing a First Information Report (FIR), putting together a charge sheet, or fighting for bail, precision is everything. Each document demands its own strategy, homing in on the essential ingredients of the offence.

Think of it this way: effective legal drafting isn't about filling in a template. It's about telling a story that fits perfectly within the law. For the prosecution, that means carefully laying out every element, from the unlawful assembly right down to the specific deadly weapon used. For the defence, the job is to find the holes in that story and drive a wedge through them.

Crafting a Robust First Information Report

The FIR is the very foundation of the prosecution's case. If it's weak, the whole structure can crumble. A well-drafted FIR for a Section 148 IPC offence needs to establish the core facts clearly and without waffle. Any vagueness is an open invitation for the defence to create doubt later on.

Here’s what you absolutely must nail down:

Establish the Unlawful Assembly: Make it crystal clear that five or more people were involved. Name the accused if you know them; if not, provide detailed descriptions.

Define the Common Object: Don't be generic. Spell out the shared illegal goal. For instance, "with the common object of forcibly stopping the construction work..."

Detail the Act of Rioting: Describe the violence. Paint a picture. "The accused persons, in furtherance of their common object, began pelting stones and shouting threats."

Specify the Deadly Weapons: This is non-negotiable for Section 148. "Armed" isn't enough. You need to list the specific weapons seen—think "iron rods, swords, and heavy wooden lathis"—to lock the case firmly into the scope of this section.

Structuring a Compelling Charge Sheet

The charge sheet is where the investigation gets its voice, turning findings into a formal accusation. To make sure it holds up in court, every single ingredient of Section 148 IPC has to be methodically laid out and backed by solid evidence. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can assist in generating a preliminary draft, ensuring all statutory elements are addressed from the start.

The language you use should be a direct reflection of the law itself:

"That you, [Accused Name], on or about [Date] at [Time], at [Location], were a member of an unlawful assembly of five or more persons, the common object of which was to commit [Specify Offence]. In prosecution of the said common object, you committed the offence of rioting and at that time were armed with a deadly weapon, to wit, a [Specify Weapon], and thereby committed an offence punishable under Section 148 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860."

This kind of precise framing leaves no room for misinterpretation. It ticks every legal box.

Building a Powerful Bail Application

On the other side of the courtroom, the bail application is the defence's first real chance to dismantle the prosecution's story. Your aim is to poke holes in their case while building up your client's position.

Here are some of the strongest lines of attack:

No Specific Role: Argue that the FIR and witness statements fail to pin any specific violent act on your client.

No Deadly Weapon: Stress that your client wasn't armed. Or, argue that the object they were holding doesn't legally qualify as a 'deadly weapon' according to case law.

Mere Presence: If it fits the facts, make the case that your client was just a bystander who got swept up in the moment and never shared the group's illegal goal.

Vague, Sweeping Allegations: Point out when the prosecution's claims are too general and fail to detail your client's actual involvement.

The Role of Legal AI in Modern Drafting

Let's be honest, drafting these crucial documents from scratch takes a ton of time and it's easy to miss a detail. This is where a legal AI assistant like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. It can generate a solid first draft of a complaint or a bail petition in minutes, making sure all the key elements of Section 148 IPC are covered.

Imagine this: you upload the FIR and witness statements, and then instruct an AI like Draft Bot Pro to draft a bail application that zeroes in on the prosecution's weak spots. This frees you up to focus on the high-level strategy and persuasive arguments, instead of getting bogged down in the basics. This combination of human expertise and AI efficiency ensures your documents are not just legally sound, but strategically sharp from the get-go.

Navigating the Procedural Steps of a Case

For any lawyer handling a Section 148 IPC case, understanding the procedural roadmap isn't just helpful—it's essential. This journey maps out everything from the first report of the offence right through to the trial. Knowing each step allows you to build a proactive legal strategy, not just react to the prosecution's moves.

It all kicks off the moment the offence happens. Since Section 148 is a cognizable offence, the police have the power to arrest an accused person without a warrant. This immediately triggers the investigation. You'll see authorities seizing weapons, recording witness statements, and gathering every piece of evidence they can to connect each accused person to the unlawful assembly and its shared goal.

The Investigation and Arrest Phase

Once the First Information Report (FIR) is registered, the police investigation hones in on proving the core ingredients of the offence. Officers will document the crime scene, take down witness accounts, and prepare a seizure memo for any weapons found. This first phase is absolutely critical; the evidence collected here forms the very foundation of the prosecution's case.

The infographic below shows the typical drafting flow, from the FIR all the way to a bail application.

This flow highlights how each document is built on the one before it, which is why the accuracy and detail in that initial FIR are so important.

The Bail Process and Charge Framing

After an arrest, the immediate scramble is usually to secure bail. An offence under Section 148 IPC is non-bailable, which means getting bail isn't a right—it's up to the court's discretion. A judge will carefully weigh the seriousness of the allegations, the specific role each accused person played, the kind of weapon involved, and the strength of the early evidence before deciding to grant or deny bail.

If you're anticipating an arrest, getting the nuances right is key. Our guide on anticipatory bail under Section 438 CrPC has some valuable insights.

Insights It's worth noting that official government data meticulously tracks crime statistics, including incidents under the IPC. Law enforcement agencies monitor the number of cases, victims, and the overall crime rate, which gives us a broader context for how prevalent these offences are. You can explore these statistics on the Open Government Data Platform India.

If the police investigation turns up enough evidence, they will file a charge sheet in court. This leads to the charge framing stage. This is a crucial milestone where the court formally lays out the charges against the accused, marking the official start of the trial.

For legal professionals, navigating these procedural hoops demands efficiency. This is where a legal AI tool like Draft Bot Pro can be a game-changer. It can help you quickly generate initial drafts of bail applications or even analyse the charge sheet against the FIR. This helps you spot discrepancies or weak points in the prosecution's story, saving you a ton of time and effort.

Practical Questions on Section 148 IPC

Let's tackle some of the common questions that pop up in practice when you're dealing with a Section 148 IPC case. Getting these fundamentals right can make all the difference.

Can a Section 148 IPC Charge Be Quashed?

Yes, absolutely. A charge under Section 148 IPC can be challenged and quashed by the High Court using its inherent powers under Section 482 of the CrPC.

This isn't just a long shot; it's a viable strategy if the prosecution's case is weak on the face of it. Think of it this way: if you read the FIR and the charge sheet and they still don't spell out the basic ingredients of the offence, you have a strong argument. For instance, if there's no mention of a deadly weapon anywhere, or if the police have only named four people, the charge simply doesn't stand up. In such scenarios, approaching the High Court for quashing the proceedings is a well-established remedy. A legal AI like Draft Bot Pro can help identify relevant case law where similar charges were successfully quashed, strengthening your petition.

What's the Difference Between Section 148 and Section 324 IPC?

This is a classic point of confusion, but the distinction is crucial. Section 148 IPC is all about the collective act—the crime of rioting while armed with deadly weapons. The law here is concerned with the threat to public peace posed by an entire group.

On the other hand, Section 324 IPC targets an individual's action. It punishes the specific act of one person voluntarily hurting another using a dangerous weapon.

So, can someone be charged under both? Definitely. Imagine a person is part of an angry mob armed with sticks and stones (that's the Section 148 offence). If that same person then steps forward and personally hits someone with their stick, causing an injury, they've also committed an individual act of assault. That's where Section 324 comes in.

The Key Takeaway While both sections involve dangerous weapons, their focus is worlds apart. Section 148 looks at the danger of the armed mob as a whole. Section 324 zooms in on the harm caused by one person's specific action.

Getting these nuances right is where a lot of arguments are won or lost. When you're dealing with overlapping sections, a tool like a legal AI can be a massive help. Draft Bot Pro, for example, can instantly pull up the fine distinctions courts have made between similar IPC sections, backed by relevant case law. This helps you frame your arguments or charges with the precision the law demands, sidestepping common pitfalls.

Navigating the maze of the Indian Penal Code demands both precision and speed. Draft Bot Pro is an AI legal assistant built specifically for Indian lawyers, giving you instant access to sharp legal research and drafting tools. Put together solid legal documents and find the case law you need in minutes, not hours. Join over 46,000 legal professionals who trust our platform. Visit https://www.draftbotpro.com to see how it can transform your practice today.